Pound crash: As a Turkish immigrant in the UK, Trussonomics feels all too familiar

As someone who moved from Turkey to the UK in pursuit of a better quality of life, along with financial and career opportunities, the pound sliding evokes feelings and worries I thought I had left behind.

In August 2018, the Turkish lira’s value tumbled by nearly 40 percent in a matter of days - and it was then that I decided I could no longer take it in the country. Many things that were once affordable, such as travelling, saving up for a flat or ordering lunch to the office, became almost out of reach.

Some of my expat friends revelled in the lira’s tumble because they were paid in foreign currency, while locals like myself had to ponder how it might affect prices in the supermarket. The future had never looked so bleak so suddenly.

I never thought I would go through a currency devaluation of this scale again in my life, not to mention this soon

I was lucky enough to find an exit and move to London for a job. It is not easy to start a new life in a foreign country - figuring out how the bus stops work, moving into a new flat, not falling asleep on the tube and missing your stop, or learning why you should never try jellied eels.

But I like to think I have done well. It came with the challenges I expected, but I never thought I would go through a currency devaluation of this scale again in my life, not to mention this soon. It has made me question whether I have a secret superpower to instigate a flash drop in currency values wherever I go.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

I always thought the British and Turkish governments shared many things in common, from an increasingly chauvinistic approach to the European Union, to a deepening love for populism, to a push to polarise people further for electoral gains. But that long list of anticipated commonalities did not include self-inflicted hits on their own economies.

Today, three-and-a-half years after moving to the UK, I can see many similarities between their financial policies, which are taking a severe toll on people’s daily lives.

Ideologically driven

Trussonomics feels very similar to Erdoganomics, in that both are purely driven by ideological, almost dogmatic, stances on the very basics of how the economy works. Their pursuit of growth at all costs aims to make the pie bigger, but not everyone’s share grows the same - if it grows at all. This comes at a heavy price, with very little fiscal responsibility displayed by both governments for years. Worst of all, neither aims to redistribute wealth; if anything, both approaches work towards increasing inequality between the rich and poor.

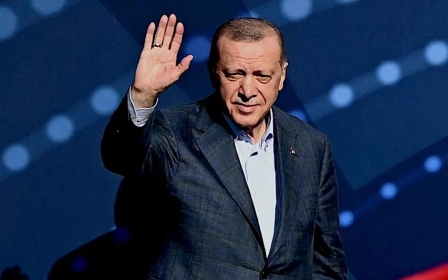

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s government turned on the money tap with very little thought for its effects in the short, medium or long term. Its decision to raise the minimum wage and other public sector salaries, amid one of the worst inflation and cost-of-living crises Turkey has experienced in decades, will at least give people some relief.

But it is another thing entirely to guarantee interest gains on savings accounts against the drop in the lira’s value via the Treasury, which is funded by taxpayers. No one knows how the Treasury plans to pay for this. The scheme raises many questions, including who it will help the most (spoiler alert: not the poor, who are barely able to make ends meet, let alone save money).

In a country where the government faces very little accountability, such questions remain unanswered. The term “fiscal responsibility” rarely features in economic discourse in Turkey anymore; the voices raising it are lost, because of the sheer magnitude of the problems facing the country. In the list of priorities, the burden on public finances falls way down the pecking order.

All of this spells trouble for whoever wins the next election in June 2023. The current governing cadre might carry on with the same disastrous mindset, worsening matters further, or the opposition parties (if they even have a shot at winning) might have to implement incredibly unpopular measures that would threaten their position before they even start.

Rising costs and stagnant wages

Unlike Turkey, there is very little to suggest that the government of British Prime Minister Liz Truss would engage in such irresponsible behaviour - and even if it tried, it would not likely get away with it, as the parliamentary Tory party may not toe the line with Truss’s cabinet to the same extent as their Turkish counterparts in Erdogan’s government. The MPs in Turkey’s governing alliance require very little convincing, functioning mostly as a rubber-stamp when the government’s actions need a veneer of parliamentary legitimacy.

Yet, none of that changes what we are seeing in the UK today: the pound is sliding, purchasing power is dropping, and families face rising costs for energy and other basic necessities, even as wages remain stagnant.

The UK government has promised help, but none of it comes close to making up the difference between what we paid for electricity and heating a year ago versus today. In addition, immigrants like myself have to deal with other consequences, such as the pound being worth less than it was a month ago against other currencies, which may worsen the situation vis-a-vis any commitments in countries we left behind.

Nevertheless, I still hope to make the UK my home. I am still grateful I was able to leave Turkey before things went from bad to worse, with no signs of improvement anytime soon.

The effects of unprecedented inflation are bad in Britain, with people having to choose between eating and heating - but at least the country has some sort of outlook on when that may come to an end. It is just a question of how much damage it will inflict in the meantime on average people less lucky than individuals like myself.

Turkey, however, has been mired in volatility for the better part of this year, with inflation floating at 70-80 percent. And the problems surrounding the country extend far beyond bad economic policy, from rising xenophobia against Syrian refugees, to the opposition’s uninspiring ideas for a new social contract, to the populist pandering of the Erdogan government. Watching this from the outside fills me with sadness.

This is why, despite its mounting issues, the UK is probably where I see my future.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.