Nobel literature prize: Annie Ernaux and the art of 'collective autobiography'

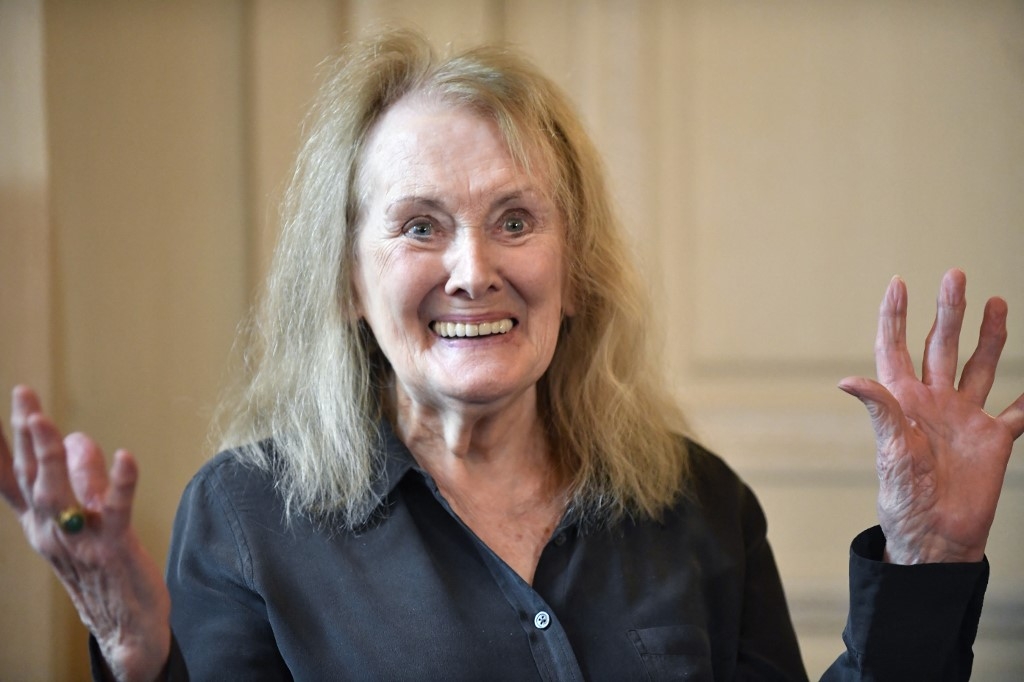

Annie Ernaux is the first French woman writer to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. She is also only the 17th woman of any nationality to win it. The Swedish Academy awarded her the prize "for the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory".

It is interesting that both she and the second woman in three years to win the prize, the poet Louise Gluck, are in a tradition of writing by women that has been consistently overlooked by literary establishments and literary prizes.

Two years ago Ernaux said, "literature is a man’s world. All the prizes, everything is controlled by men. Now people say I have legitimacy, but I’ve had to wait to be over 50".

'All the prizes, everything is controlled by men. Now people say I have legitimacy, but I’ve had to wait to be over 50'

- Annie Ernaux

The daughter of grocers in a small Normandy town, 82-year-old Ernaux has been writing for half a century. She has produced more than 20 books which examine a life marked by great disparities in the areas of class, gender and language.

Although she describes her work as fiction, she was an early practitioner of what nowadays is called "autofiction".

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Perhaps her earliest antecedent is the British novelist Dorothy Richardson, whose sequence of 13 novels, Pilgrimage, published between 1915 and 1967, was the first to explore the importance of female experience through autobiographical fiction.

Unlike much autofiction, however, and like her heroine Simone de Beauvoir, Ernaux’s examination of the female experience is a political act, its mission to reveal social inequality.

'Brutally direct'

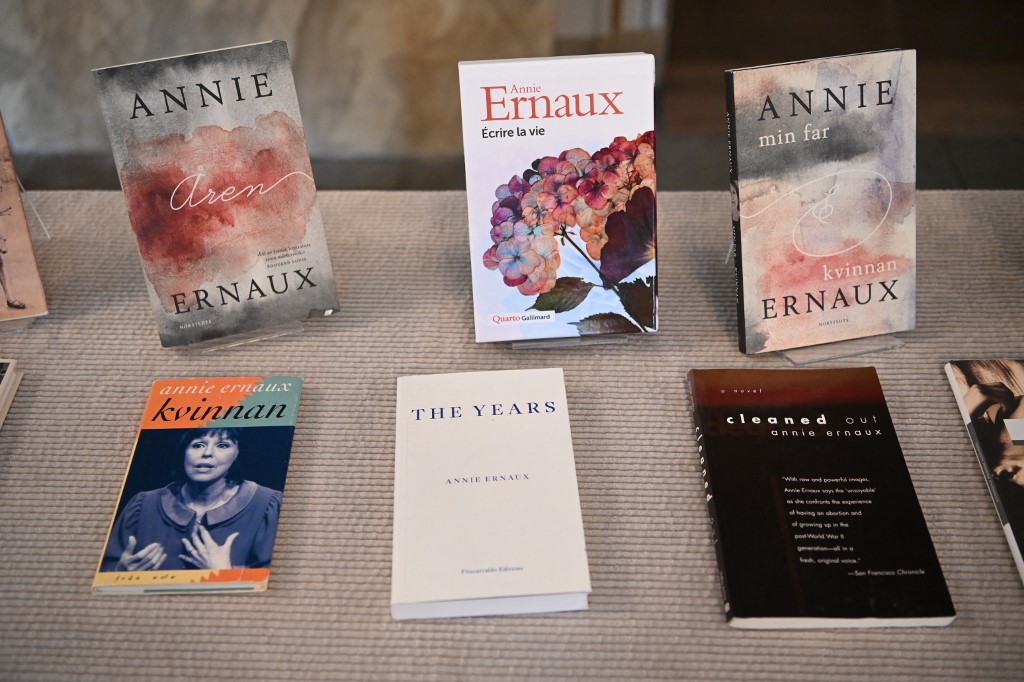

Ernaux began her working life as a school teacher and is now taught in France. Her first book, Cleaned Out (Les armoires vides), published in 1974, was about her illegal abortion in 1963. She went on to write of her working-class origins in postwar France, of teenage eating disorders, the descent of her mother into Alzheimer’s, the deaths of her parents and the experience of breast cancer.

Two of her books are an account of a compulsive and obsessive sexual relationship. Simple Passion (Passion simple), published in 1991, and her most recent book, Getting Lost (Se perdre), published last month, describe her affair with a much younger married Soviet diplomat. She was approaching 50 years old. He was in his thirties, a man with a taste for flashy cars who had obnoxious political views.

Ernaux has won many French prizes, including the Marguerite Duras Prize. But it was not until 2019 when her novel The Years (Les Années) was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize that she received international recognition. The narrative of The Years begins in 1940, the year of the author’s birth and ends seven decades later.

Although it is an account of the author’s life, told in the third person, its central concern is the social, political and cultural landscape through which she moved. It is a book that combines the local and intimate with a great, collective sweep of history, and is similar to Elena Ferrante’s Neopolitan quartet. It has been called "the first collective autobiography" and is generally thought of as her masterpiece.

Ernaux is notable for her rejection of the French concern for exquisite well-turned language. She has described herself as using words like "a knife"; she uses a minimalist style which she describes as flat writing, "écriture plate". She says her language is "brutally direct, working class and sometimes obscene". Or as the Nobel committee put it, "uncompromising and written in plain language, scraped clean".

Coming from the early frontlines of feminism, she could be seen as outmoded by modern feminists. Unafraid to reveal those abject and debasing aspects of a relationship with a married man - waiting endlessly by the phone, enduring unpalatable political opinions, being used in every way possible - she is out of step with the new form of political correctness. And yet, like her heroine, Simone de Beauvoir, she is profoundly and radically feminist.

Unafraid of risk

In Simple Passion, she wrote: "Naturally I feel no shame in writing these things because of the time which separates the moment when they are written - when only I can see them - from the moment when they will be read by other people, a moment which I feel will never come.

"By then I could have had an accident or died; a war or a revolution could have broken out. This delay makes it possible for me to write today, in the same way I used to lie in the scorching sun for a whole day at 16, or make love without contraceptives at 20: without thinking about the consequences."

Ernaux’s Nobel Prize in Literature is not only a triumph for feminism, but also for small independent publishing. In the US, Ernaux is published by Seven Stories Press.

She was one of their first seven writers for whom they named their press.

'Annie Ernaux has been writing for 50 years the novel of our country’s collective and intimate memory. Her voice is that of women’s freedom and the century’s forgotten'

- President Emmanuel Macron

In the UK she is published by Fitzcarraldo Editions, which publish three of the last eight Nobel Literature laureates. Perhaps most significant is that these three are all women: Olga Tokarczuk, Elfriede Jelinek and Svetlana Alexievich.

We are at a time when the publishing landscape on both sides of the Atlantic is increasingly corporate and timid. Executives believe it is difficult to publish "midlist" or small books.

They are cautious about taking on a writer and backing their talent over a prolonged period, liking to acquire debuts in splashy auctions, routinely discarding writers mid-career.

They would do well to note that the prize shortlists are populated by small presses led by editors unafraid of risk, prepared to back their taste, in for the long haul of an author’s writing life. Fitzcarraldo Editions is a shining example of this.

On hearing the news of the prize, France’s President Emmanuel Macron tweeted: "Annie Ernaux has been writing for 50 years the novel of our country’s collective and intimate memory. Her voice is that of women’s freedom and the century’s forgotten."

The philosopher and sociologist, Didier Eribon, said: "I have such admiration for her, not just as a writer, but for her activism."

'Liberating force of writing'

Ernaux’s activism has included support of the Yellow Vest movement, which protested against rising fuel prices in France and the decline of living standards, and support of the BDS policy against Israel. Legalised abortion is another cause close to her heart and she says she will "fight to my last breath so that women can choose to be a mother or not to be".

She asserts that the Nobel Prize will not change her life, but that it will help her fight "for women and the oppressed".

Anders Olsson, chairman of the Nobel committee, wrote: "Annie Ernaux manifestly believes in the liberating force of writing… And when she with great courage and clinical acuity reveals the agony of the experience of class, describing shame, humiliation, jealousy or inability to see who you are, she has achieved something admirable and enduring."

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.