Power and pilgrims: How Iran uses Arbaeen to spread influence in Iraq

Mehran, Iran-Iraq border - On the side of an unpaved road, Mohammad-Reza Bagheri implores people to let him polish their shoes: "Please, please, I'll be fast! Let me clean your shoes!" A thin patchy beard covers his sunburnt face as he sits, brush in hand, looking at those hastening on their way.

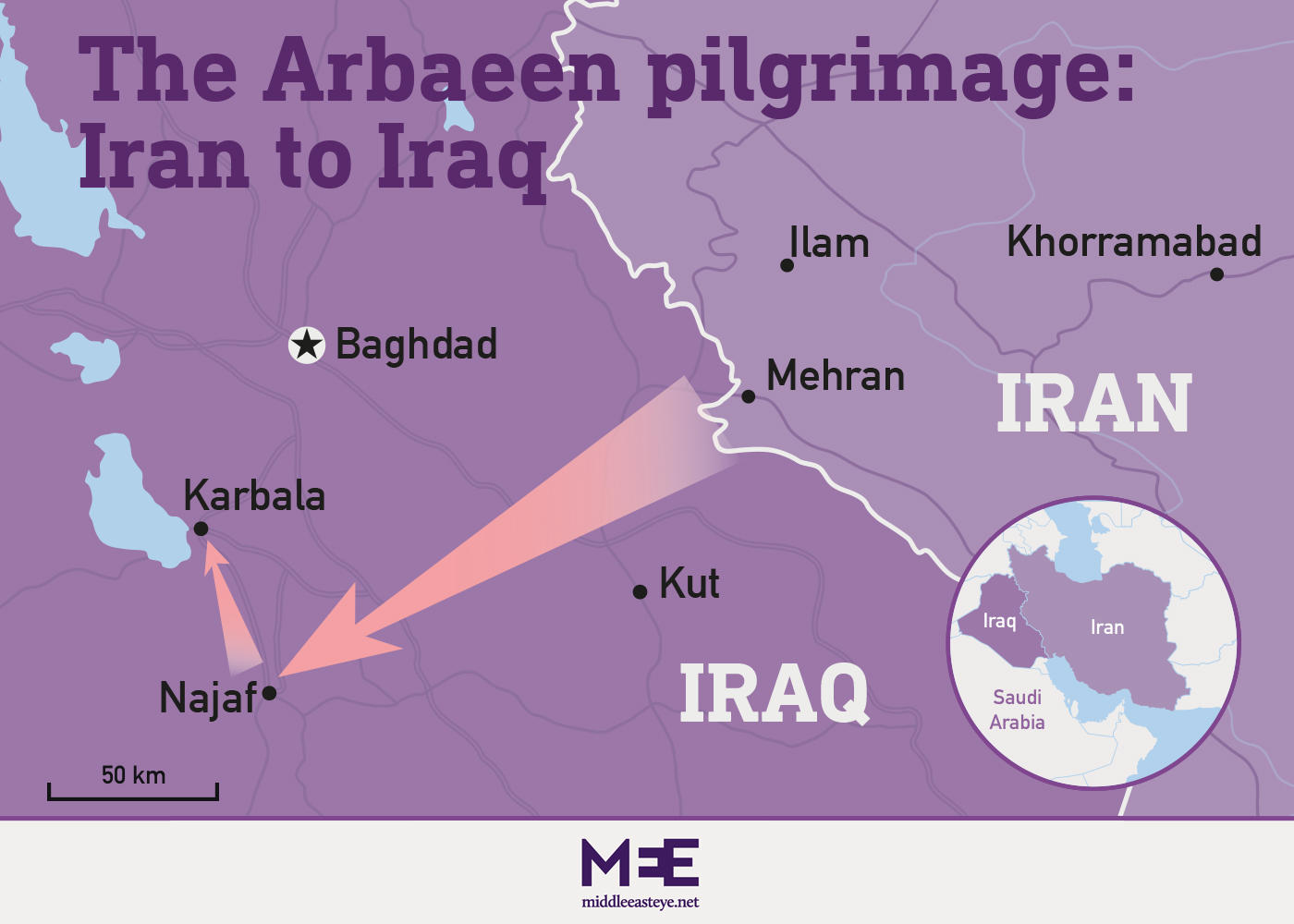

But Bagheri, 19, is not a shoe shiner. He is not a beggar. He does not even demand money. Bagheri is a pilgrim observing Arbaeen, and the road beside which he sits connects the Iranian city of Ilam to Najaf, about 400km across the border in Iraq.

Arbaeen marks the end of the 40-day mourning period for the death of the revered Hussein ibn Ali, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad and the third Shia Imam, who lived more than 1,300 years ago.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

For Shia, who make up an estimated 95 percent of Iran’s Muslim population, it’s an auspicious commemoration whose religious origins date back centuries. As an Islamic pilgrimage, it is rivalled in sheer numbers by those who undergo the three different types of Hajj at Mecca and Medina in Saudi Arabia.

For years, Shia political interests across the region, notably Iran, have used the event to mobilise their forces, secure their political agenda and demonstrate a show of power to rivals. It has become even more pertinent in recent years, amid Tehran’s growing involvement in Iraq and observations about the involvement of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

But this year Bagheri could not finish his pilgrimage: he was stopped by the Iranian border guard for trying to cross the border without documentation. "I was not worthy of being a pilgrim of Imam Hussein's shrine," he says, as he shines a pair of shoes. "So, I decided to stay at the border and clean the shoes of those accepted by the Imam to set foot in Karbala."

Destination: holy city of Karbala

Five million pilgrims headed for Iraq during this year’s Arabeen, according to the Iranian authorities, with numbers heading back to pre-pandemic levels (the official number for 2021 was only an estimated 80,000).

Hussein ibn Ali is one of the most revered figures in Shia Islam, not least among the Twelver Shia. In 680 AD, he and his followers rose up against Yazid, the caliph of the time, who had assumed power after the death of Muawiya, his own father. The final battle, after a long struggle, took place in Karbala the following year, where Hussein and his small army were killed. The commemoration of Arbaeen is on the 40th day after the death of Hussein ibn Ali (itself known as Ashura), which this year fell on 17 September.

But pilgrims begin flocking to Iraq much sooner: thousands enter Iraq on the day of Hussein’s death, some even walking from Mashahd - Iran’s second-largest city, some 2,000km from Najaf. They then head on foot a further 80km from Najaf to the holy city of Karbala and the site of his tomb.

Visiting the shrine of Hussein ibn Ali has always been an important religious ritual for Shia Iranians, even before the 1979 revolution. It is less expensive and challenging, although it does involve a lot of walking. Just as haji refers to a pilgrim who has embarked on the Hajj, so the Farsi word karbalaei means someone who has visited the Shrine in Karbala.

Shahin Dokht Motevalli, 77, visited Karbala before the founding of the Islamic Republic: only her grandmother had previously visited the shrine. But that grandmother taught her how to pray and gave her a religious education: when she was old enough, Motevalli followed in her footsteps.

"My grandmother always recalled how she went to Karbala alone on the back of a horse, despite my grandfather's disapproval," Motevalli tells MEE on the phone.

"The stories she told about that pilgrimage sounded powerful and magical to me. In our family, she was known as a strong and religious woman; for me, she was a role model, religiously and personally.”

But after the revolution and the establishment of the Islamic Republic, Motevalli never again went on the pilgrimage.

What decided it for her was during the Iran-Iraq war (1980-88), when the authorities said that the “path to Jerusalem” - a slogan to recruit volunteers - passed through Karbala”, despite the fact that the pilgrimage stopped during the eight-year conflict.

“I decided that no more I should go back to that shrine. Instead, I continued praying and doing my religious duties from my home. Imam Hussein does not need us to go there if we seek goals other than respecting his martyrdom."

'The road to Karbala was so busy, I had trouble finding a spot to sleep'

- Rasoul, pilgrim

Now the pilgrimage is more popular than ever. Waiting in a long line at the crowded and chaotic Mehran border crossing is Rasoul, a rice grower in his early forties from the northern city of Behshahr. "As soon as you arrive in Najaf, everything will be free," he says.

Rasoul embarked on his first pilgrimage to Karbala in 2019. That year, 3.5 million Iranians participated, setting a then record. "I wanted to participate in the walk and be in Karbala on the exact day of Arbaeen. But everywhere was heavily packed with mourners, and even at night, I could not enter Imam Hussein's holy shrine,” he recalls. “The road to Karbala was so busy, I had trouble finding a spot to sleep. But still, it was a great experience."

One night, he slept on the cement floor of a half-built building in Najaf. On the way to Karbala at least he was able to sleep in different mokebs, the resting places where pilgrims can participate in religious mourning, eat, drink, and stay overnight, all free of charge.

But once Rasoul arrived in Karbala, the best he could find was a residential backyard that left its door open to pilgrims. "You see a sea of people all in black,” he says. “They have one thing in common: their love for Imam Hussein. To me, it was a reminder of how many people in the world share the same feeling with me."

Scholar Arash Azizi, author of The Shadow Commander: Soleimani, the US, and Iran's Global Ambitions, describes the commemoration as "a genuine effort by the devout Shia to take part in a pilgrimage experience" akin to a socially popular carnival, that draws from all walks of life.

"It is also an opportunity to take a fun and often adventurous international trip on [the] relatively cheap. It’s an attractive option for millions. It also helps build national-religious legitimacy at home and benefits some segments of the population in a variety of economic, spiritual and social ways.”

Tehran forges links with Iraq

During the past decade, western sanctions and regional rivalries and conflicts put great pressure on Iran’s ruling establishment. The more issues the authorities face, such as the recent outbreak of protests, the more critical Arbaeen becomes to Iran as a theocratic state. Azizi says that for the Iranian authorities “it's an important tool for bolstering ideological and national-religious legitimacy”.

The commemoration, he added, builds further material links with Iraq, as Tehran tries to boost its sphere of influence across the region among countries with sizeable Shia populations, including Syria, Lebanon and Bahrain.

The idea itself emerged much earlier, during the early 1980s, when the Hezbollah movement gained power in Lebanon and received backing from Tehran, including training from the IRGC.

When the Iran-Iraq war ended in 1988, Tehran's political strategists made overtures towards political movements in Iraq opposed to Saddam Hussein.

After 2003, when the US-led coalition removed Saddam from power, the occupying western powers opened the door for Iran to increase its influence in the country. After that, small-scale organised pilgrimages began: since then, the Arbaeen has grown and come to have increasing importance for politicians in Tehran as an expression of Iranian power.

The Iranian authorities’ presence in Iraq has faced problems, especially since the protest movement which emerged across Iraq in 2019, says Azizi. “But events like Arbaeen have helped expand its material presence there, and that won't be so easily undone.”

US sanctions have devastated Iran's economy: in late October, one dollar was worth 338,000 rial, compared to 32,000 rial when the US nuclear accord was agreed in 2015, with the US withdrawing from the deal in 2018 and reimposing sanctions. But the government is always ready to pour money into the Arbaeen. Tehran subsidises the prices of the plane, train and bus tickets between the two countries; provides free internet for the pilgrims in Iraq; and even allows those serving their obligatory military service or light sentences in jail to request leave to participate. NGOs, such as Iran’s Red Crescent, deploys all its employees and volunteers at the Iran-Iraq border and across the road where pilgrims walk between Najaf and Karbala.

It’s hard to put a figure on how much the Iranian government and its agencies spends. The most essential support comes in the form of non-refundable loans to those who establish mokeb along the route. Official data showed that at least 2,507 mokebs were funded this year inside Iran alone, with more funded in Iraq. Tehran's municipality dedicated more than $7.1m to food, water and rest of pilgrims, while Ilam province invested more than $190m - huge amounts in a country in a perilous economic situation. But the establishment believe it is essential to ensure support especially from the poorer and more religious sections of society.

And while the Iranian authorities apply strict rules for its citizens travelling abroad, during Arbaeen most regulations turn softer. For example, this year, the government permitted citizens with expired passports to leave the country.

In a minivan between the Mehran border crossing and Najaf, a man in his mid-30s happily shows fellow passengers a passport photo and asks whether it looks like him.

"Officers checked the passport several times, but I answered all of them so confidently," he excitedly explains, his speech interspersed with swearing and Tehrani underworld slang. "It's a miracle that I passed the border. I told the officers that I grew old, and that's why I look different from my photo."

He is one of a group of four: all sport tattoos and knife scars on their arms. Aside from checkpoints, the vehicle is sometimes flagged down by Iraqis who give pilgrims free bottles of water. The quartet of tattooed pilgrims compete to grab as many bottles as possible, then hurl them empty from the moving van during the rest of their noisy four-hour journey to Najaf.

Stopover in Najaf

Najaf is another sacred city and an important centre of Shia political power in Iraq, where hundreds of thousands of pilgrims stay overnight. The shrine of Imam Ali, the first Shia Imam and the father of Hussein, is located in the heart of the old city. Hundreds of thousands of pilgrims stay overnight before beginning the last phase of their pilgrimage and heading to Karbala.

In Najaf, shops at the Shrine of Imam Ali sell religious souvenirs such as rosaries, agate rings, and prayer mohrs. Most shopkeepers speak Farsi to bargain with the millions of Iranian customers every year. Tens of construction sites ring the shrine, building hotels and hostels for future pilgrims.

The main area of the shrine has also been expanded and reconstructed by Setad-e Bazsazi Atabat Aliat, an Iranian governmental office responsible for rebuilding and renovating Shia sacred shrines in Iraq.

The commitment is necessary: observers note that, for Tehran, Najaf is as important as Karbala with its role as the power base of Moqtada al-Sadr, an influential Shia cleric with a powerful political following whose movement won the most seats in the last Iraqi parliamentary elections. Sadr and his family of high-ranking clerics were for decades Iran's closest allies in Iraq. But increasingly Sadr acted more and more independently of Iran, eventually brokering alliances with Tehran’s opponents and branding himself an Iraqi nationalist opposed to foreign interference.

Ali, an Iranian political scientist using a pseudonym for his own safety, told MEE: "Following Sadr's recent political manoeuvres and the armed conflicts between his supporters and the Iraqi army, the Iranian political elite is deeply cautious about Sadr's next move.”

On 3 September, in a rare move, Sadr published a Farsi Twitter message, urging Iranian pilgrims to legally enter Iraq and respect the law during the pilgrimage. For the Iranian government, it was a warning from a former ally.

"Tehran knows that Sadr is unpredictable, specifically after his recent so-called retirement from power, followed by a deadly confrontation between his own armed group and the Iraqi military,” said Ali. “So, Iran thinks they need to teach him a lesson, and nothing could serve them better than a huge mobilisation during Arbaeen.”

Ali said that there were several reports of the IRGC deploying its forces into Iraq under cover of the Arbaeen pilgrimage. “So far, we don't know if it is an accurate claim or if it's just propaganda. But either way, Iran is responding to Sadr's political moves by using Arbaeen.”

Iranian officials have never confirmed the deployment of IRGC forces during the Arbaeen walk for military reasons. However, the state-run media said that the IRGC airforce sent "tons of food and water to Iraq" to be distributed among the Arbaeen pilgrims. The defence ministry, led by an IRGC commander, also deployed its forces at the Iran-Iraq border to assist pilgrims. And the IRGC-affiliated news agency Tasnim reported that Esmail Qaani, the head of Iran's IRGC Quds Force, participated in the Arbaeen walk.

Commemoration of Soleimani

Nowhere in Iraq is there a stronger demonstration of Iranian power than on the 80km road that connects shrine of Imam Ali in Najaf and his son, Hussein ibn Ali's shrine in Karbala.

This trek is more than just an act of religious ritual. In February 2014, Qassem Soleimani, the late commander of IRGC Qods force, said that the participation of millions of pilgrims in the walk between the two cities was akin to a military exercise. "This is our power; this religious manifestation of 20 million Shia, this show of power is much stronger than military parades showing airplanes, tanks and canons."

The US assassinated Soleimani in 2020 with a drone attack at Baghdad international airport. But the Iranian authorities still adhere to his manifesto about the Arbaeen walk and encourage increasing numbers each year to participate.

"With our enemy countries in the West, we are at war, and for this war, we must keep our forces trained and ready," said Arad, an IRGC infantry colonel, speaking on condition of anonymity because he was not authorised to speak publicly (Arad is a pseudonym).

He said that each year the walk is undertaken by hundreds of Basij forces as a drill to keep them physically and mentally ready for battle. The force comprises of paramilitaries, commanded by the IRGC, who are deployed to crack down on anti-government protests in Iran.

“All our defenders of the shrine have at least once walked the distance between the two sacred shrines," he said. Defenders of the shrine is the official term that the authorities in Tehran use for the IRGC forces fighting in Syria and Iraq.

According to Arad, the US and coalition forces in the Middle East closely monitor the walk and the annual pilgrimage, providing Iran with an opportunity to demonstrate its military power.

"They monitor us, and we monitor them; if they hit us, we'll hit them back,” he says. “They show us their power by attacking our commanders and forces in Syria and Iraq, and we show them our power by the number of people we can mobilise if they begin an all-out war.

“When it is necessary, we show them our power by attacking their bases in Iraq, as we did in Ain al Assad," he said, referring to the US base which was hit by several missiles in January 2020 in response to the assassination of Soleimani.

There is also the propaganda. Throughout Iran, it does not come as a surprise to see posters and large billboards covered with images of Soleimani, who is remembered as a martyr of the republic.

But similar images are also evident beyond the border posts in Iraq itself. Often the posters show him alongside Abu Mahdi al Muhandis, the deputy head of the Iran-backed Hashd al-Shaabi Iraqi paramilitary force who was assassinated in the same attack. The numbers of such billboards only increase as the pilgrims approach Najaf.

From the city, it is straightforward for the pilgrims to find their way on to Karbala: even if they ignore all the placards and signs in Farsi, they need only follow as their fellow pilgrims depart from Imam Ali's shrine. Then there are the 1,452 amood, a series of 50-metre high poles that line the highway between the two cities. Some display photos of the slain forces of Hashd al-Shabi or religious declarations.

In a mokeb, at amood 157, Golbahar, an elderly Afghan woman carrying a black, green and red flag of Afghanistan, takes a break from her walk. "Everything has changed in the past years," she reflects.

In 2007 she went to Karbala for the first time, a refugee in Iran who had joineda fellow Afghan Shia. "That year, we were not many Afghans going to Karbala, maybe 200 or 300,” she recalls. “Now there are thousands of Afghans here."

Most Afghan pilgrims are refugees: despite the usual restrictive measures imposed on their movement by Tehran, Arbaeen allows them to travel across the country and even leave. In previous years, Tehran has helped Afghan Shia pilgrims leave Afghanistan, although this number has been cut since summer 2021 due to the Taliban's rule.

"For our relatives in Afghanistan, it's complicated to come to Karbala, but the [Iranian] government helps the documented refugees to join the Iranian pilgrims,” says Golbahar. “It is good, you know! It is the only time we can travel, and we can also visit the holy shrine of Imam Hussein and Imam Ali.”

Should the state pay for Arbaeen?

During the last days leading to Arbaeen, the streets and highways in Karbala are closed to cars, their place taken by rivers of black-clad people flowing toward Hussein ibn Ali's shrine.

But it is impossible for thousands, especially the elderly and children, to get close to the shrine due to the sheer numbers. And while Karbala is full of Shia of all nationalities, it is Iranians who pack all the mokebs in Karbala, leaving no accommodation close to the epicentre.

It’s also in Karbala, where the Iraqi Shia militia and political factions, backed by Iran, show off their power as a mark of Tehran’s reach.

Haj Jafar stands at the entrance of a mokeb named after Fatemeh Zahra, the daughter of the prophet Muhammad, sporting a long white beard, dressed in black and welcoming pilgrims seeking a place to rest. He urges them not to stay more than 48 hours, to make space for the thousands behind them streaming into the city. This is the 12th year Jafar, who is in his mid-60s, has run this mokeb: each night it sleeps about 100 people. His team of 17, however, cook three portions of food for 200, just to cater for those who stay shorter. According to Iranian government data, Iranian mokebs cooked and distributed 12 million portions of free food each day during the last quarter of this year's Arbaeen.

"We do it because of our love for Imam Hussein and to make God happy with us," Haj Jafar says. He is welcoming to the new arrivals, and freely shares his memories of previous years of service in Karbala. But when asked about Iranian governmental aid he may have received, reluctantly, he will only offer: "The biggest part of the money we receive is from the donations made by ordinary people. Of course, the government also helps, but that is not enough."

Other mokeb organisers MEE spoke to are even more guarded about possible funds from the government. The unspoken suggestion is of an unwritten agreement not to discuss the issue.

And the money spent on Arbaeen is an issue for many Iranians, not least against the backdrop of the economic crisis.

In 2015 Hashem, 34, a social worker from Sarpol-e Zahab, in western Iran, was delighted to receive a government loan to participate in the pilgrimage with his parents. But life changed for him and thousands of others in November 2017, when a 7.3 magnitude earthquake killed 620 people and left more than 60,000 homeless in Kermanshah province. Tens of villages were entirely destroyed; some have not yet been reconstructed, their ruins laid out on both sides of a road linking the Iran-Iraq border crossing at Khosarawi with Iraq to the provincial capital, Kermanshah.

"Before the earthquake, I had always appreciated the money the government gave us for the pilgrimage," he says. "It was so easy to receive the loan for Arbaeen, but to repair our house after the earthquake, I faced thousands of issues. It was like getting trapped in a labyrinth of obstacles. In the end, my family had to borrow money from friends and relatives to fix the building."

Now he believes that the funds earmarked for Arbaeen should instead support the poor of Iran.

"I don’t believe any more in what the government says. If they want to do good to people, why do they take the money we need from us, and spend it in Iraq? I think they don't even believe in Imam Hussein; the only thing they know and work well for, is their throne."

Main photo: Shia pilgrims gather in Karbala on 17 September 2022, to mark Arbaeen (AFP).

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.