How Israel's Gaza blockade separates mothers from their premature babies

It was seven months into her pregnancy when Yasmeen Ghanem was informed she needed to give birth prematurely.

The 28-year-old Palestinian then rushed to make arrangements to travel to Jerusalem from her hometown in Gaza, where the medical infrastructure has been badly impacted by years of Israeli-led blockade and bombardment.

A week later, she gave birth to a baby girl, Sophie, who weighed less than 800 grams and needed further medical attention at al-Makassed hospital in occupied East Jerusalem.

Ghanem, however, was forced back to Gaza by Israeli authorities, according to the permit conditions that did not allow her to remain in Jerusalem after being discharged from the hospital.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"I felt so guilty leaving her alone while she needed me the most," Ghanem told Middle East Eye, as she described her tearful journey in the taxi back to Gaza.

"But it was not even my choice."

Sophie is one of tens of thousands of Palestinian children who, since 2007, have been separated from their parents while being treated outside the besieged Gaza Strip.

Under the Israeli siege, Palestinians who want to pass from Gaza through Beit Hanoun (Erez) crossing to reach the occupied West Bank or Israel need to obtain an exit permit from the Israeli army. Such permits are granted only to people who fall within very limited categories - including critical medical and humanitarian cases, staff of international organisations, or students with scholarships to study abroad.

In nearly half of the cases concerning minor patients, the Israeli army either rejects or delays giving permits to parents, leaving sick children to be accompanied by another relative.

'She is growing up alone'

When Ghanem returned to Gaza, depression symptoms were unmistakable, according to her psychiatrist.

"This is not how I planned my relationship with my baby. She is growing up alone in a place that I cannot even reach," Ghanem told MEE.

"The fact that there are some hundreds of metres and three checkpoints between me and my daughter kills me every second," she added.

The Gaza Strip is less than an hour's drive away from Jerusalem without Israeli checkpoints.

'Seeing babies crying without their mothers around was beyond sad and devastating'

- Yasmeen Ghanem, Palestinian mother

A week after her return, Ghanem asked the Tel Aviv-based NGO Physicians for Human Rights to file a request on her behalf to obtain a new permit.

The group, which works on similar cases with Palestinians in Gaza, secured a one-month permit for Ghanem that allowed her to go to the hospital but not visit anywhere else in the city.

Ten days after they were initially separated, Ghanem was reunited with Sophie, while her father, Muhammad Ghanem, still knows his baby only through pictures.

"I was lucky to get the permit. I was the only mother from Gaza visiting my baby at the hospital," Yasmeen Ghanem said.

"Seeing babies crying without their mothers around was beyond sad and devastating."

Due to the strict restrictions in Ghanem's permit, she can't stay at a hotel in Jerusalem while her daughter recovers. As a result, she went for only for a single night in each week.

After her one-month permit was over, Yasmeen and Muhammad applied again for new permits. Yasmeen got a one-week extension while Muhammad received no response to his application.

Doctors' hands tied

At the al-Makassed hospital, one of the leading medical facilities for Palestinians in the occupied city, there are 12 unaccompanied premature babies.

It's a "miserable situation", said al-Makassed neonatology department chief Dr Hatem Khamash.

"This has been the case for years, and no real solution for this miserable situation can be seen on the horizon," Khamash told MEE in a phone interview.

The separation of children from their parents at this early stage leaves negative consequences on both the physical and psychological well-being of the babies, he added.

"These babies are denied their mother's breast milk, besides physical connection, which is crucial for their emotional development."

The only way Khamash can keep these mothers in Jerusalem is by not discharging the infants from the hospital, which he says is difficult due to limited capacity.

"Even if we want to, it's not comfortable at all for them to live at the hospital for weeks, or maybe months," he said.

Aseel Baidoun, advocacy and campaigns manager at the UK-based Medical Aid for Palestinians (MAP), said this has been an issue that MAP has been campaigning on in the UK for years.

The Israeli policy is part of the "systematic discrimination and fragmentation" against Palestinians in the occupied territories, she said, and her group is working to raise it with policymakers in the UK.

"This is one of the brutal examples of how Israeli policies dehumanise Palestinians and deprive them of their basic human rights," Baidoun told MEE.

Bureaucratic process

Even though Israeli permits to leave Gaza are granted in "exceptional humanitarian circumstances", the slow and bureaucratic process of applying makes it only worse for Palestinians, according to Physicians for Human Rights Israel's director of the occupied territories department, Ghada Majadli.

Most permits that are granted are reserved for mothers and are valid only for one day, while most fathers are not granted access to see their babies, Majadli told MEE.

"Sometimes we try to get a permit for one of the parents just to go and take their discharged baby from the hospitals, but we don't always get this; other relatives go and take the baby back to Gaza," she said.

Khamash said their department witnessed similar cases as those described by Majadli. The situation leaves them in a dilemma, fearing that it would be illegal to dispatch a child to someone other than their parents.

"But what other options do we have?" he said.

There are currently two babies in al-Makassed who are ready to be dispatched, but none of their parents has been granted an Israeli permit yet.

"We need these incubators for newborn premature babies; this situation badly affects our capacity," Khamash said.

The Israeli army turns down permit requests when a minor's guardian application is rejected, based on unspecified security reasons or due to purported errors in the submitted documents.

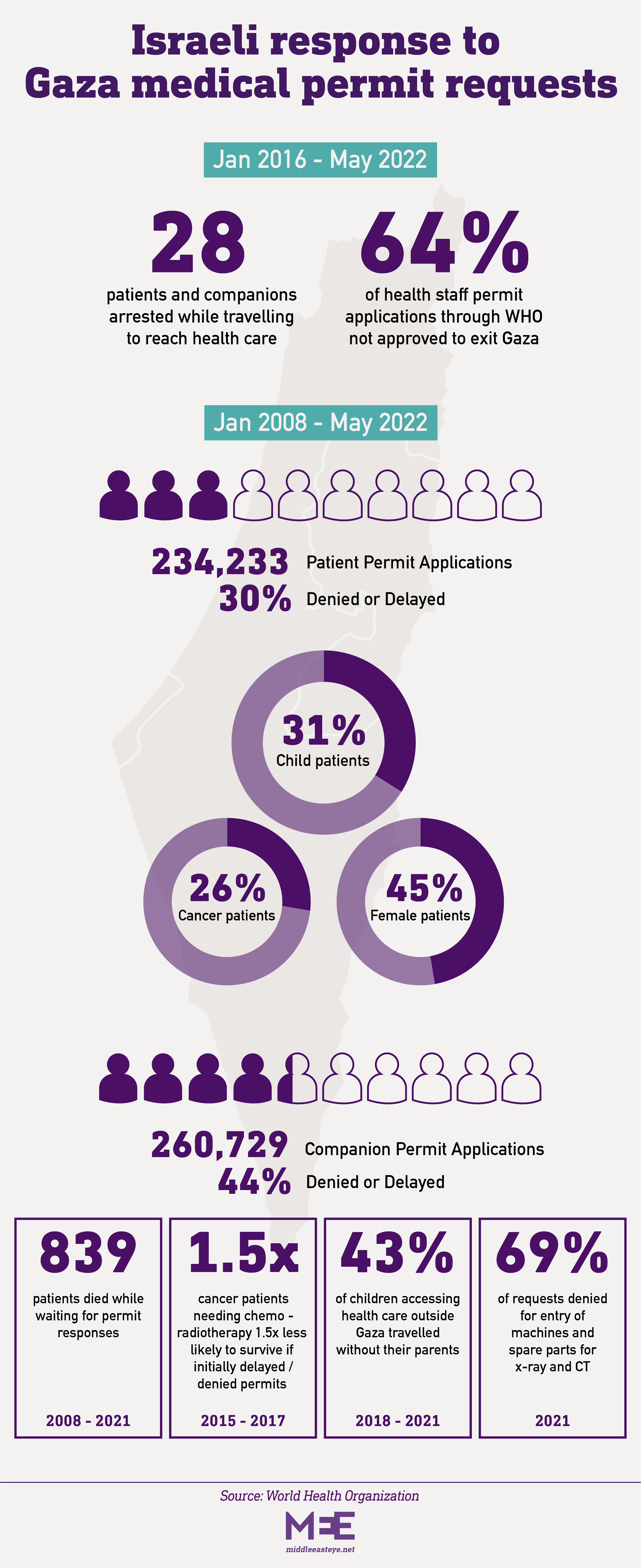

Between 2018-2021, around 43 percent of children travelled without parents, according to the World Health Organization.

'I can't wait to have her back'

Yasmeen Ghanem was only 14 years old when Israel imposed its siege on the Gaza Strip in 2007.

She survived four major military offensives Israel waged against Gaza, in 2008-09, 2012, 2014, 2021 and in August this year, which have together pushed Gaza's health infrastructure to the brink of collapse.

According to the United Nations, chemotherapy, radiation therapy and PET/CT scans are unavailable in the enclave.

This leaves patients among the two million-strong Palestinian population who require vital and life-saving medication with no option but to seek treatment abroad.

"I always heard that Gaza is the biggest open-air prison in the world, but I didn't really understand what this meant until I wasn't able to see my baby who is only dozens of kilometres away," Yasmeen Ghanem said.

The experience has changed how the new mother views Israel's 55-year-long occupation.

"I always feared being killed or getting one of my loved ones killed in an explosion.

"But I never thought I wouldn't be able to be with my daughter even when she is alive. I'm very desperate and can't wait to have her back."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.