Why Palestine matters to Netflix (and why Netflix matters to Palestinians)

Palestine has a rich history of cultural resistance against Israeli occupation and military aggression in the form of movies, literature, and artwork.

Iconic Palestinian films that have drawn international acclaim include Elia Suleiman’s film Divine Intervention, Hany Abu-Assad’s Academy Award nominee Paradise Now and Annemarie Jacir’s Salt of this Sea.

Yet it is only within the past few years that streaming platforms, such as Netflix, have included Palestinian works in their catalogues in a significant number. So why now?

Any previous reluctance on the part of streaming platforms may have been down to the promptness with which movies critical of Israel were labelled antisemitic by pro-Israel groups.

As a result, beyond such platforms, Palestinian stories have traditionally not been a major part of international commercial screening.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In her book Palestinian Cinema in the Days of Revolution, Professor Nadia Yaqub of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill traces the development of Palestinian cinema after the Nakba of 1948, the forceful removal of more than 700,000 Palestinians from their homes and the creation of the Israeli state.

She asserts that Palestinian cinema sought to visualise Palestinian spaces and people in the face of state-backed violence and generate solidarity, not sympathy, from its viewership.

Palestinian stories have achieved this despite minimal institutional support. While winning awards such at Cannes and Bafta, Palestinian films were not available for viewing by the general public.

The likelihood is that anyone who has watched a Palestinian movie or documentary before 2022 had likely done so out of an interest in the Palestinian issue. The actual process of finding such films would also have been a laborious struggle outside of academic film screening circles, such as the ones created by the Middle East Institute and Center for Palestine Studies at Columbia University.

Both regional and international streaming platforms, with the exception of Netflix, have also generally steered clear of commissioning Palestinian content.

The presence of these platforms in households and on phone screens around the world is seemingly universal, so it goes without saying that through their choice of content, they have the ability to shape public opinion and influence viewer ideology.

But the decision to stream any given show is not a one-way process, as data analytics also inform what gets commissioned and aired. Put simply, knowing a particular genre will be received well with audiences helps decide what gets made or licensed.

Determining audience size

As a streaming platform, Netflix focuses on the viewing needs of individual users, and has a user base of approximately 223 million paying customers worldwide in 2022.

Netflix’s core growth problem is the acquisition of new customers and converting them into paying subscribers and there are two levers through which Netflix solves this: pricing and content.

In the first half of the 2022, Netflix lost approximately 1.2 million customers, 700,000 of which were the casualty of Netflix pulling out from Russia because of the war against Ukraine, and the rest from the US and Canada because of steep pricing.

However, in the second half of 2022, Netflix revised its pricing model by introducing lower subscription rates for streaming with adverts, as well as by limiting password sharing between family and friends.

Netflix’s acquisition of new customers typically works through users getting attracted to original content unavailable elsewhere and a fear of missing out generated through social media chatter.

When users first sign up, they are asked what kind of shows or movies they like to watch, and Netflix builds a recommendation strategy based on the user’s choices to retain the user.

To decide the type of content Netflix should stream, it needs to know what its users want to watch and analyse the data it collects.

To stream Palestinian stories, Netflix would have researched the market size it could capture in the Middle East

It conducts market sizing by identifying the Total Addressable Market (TAM) or the total market that could demand online streaming, the Serviceable Addressable Market (SAM) or the segment of TAM that is within geographical reach, and, most importantly, Serviceable Obtainable Market (SOM), which is the total amount of SAM it can capture given the competition.

It builds multiple ideal customer profiles (ICPs) by predicting what its users do, where they’re from, what their interests are, and what they spend their time and money on.

To stream Palestinian stories, Netflix would have researched the market size it could capture in the Middle East, the kind of people who would watch Palestinian stories, and predicted its growth in its regional and global customer base.

From its existing users, it collects IP addresses that reveal their location, their "watch history", "search queries", and "time spent watching a show" that reveal the kind of content their existing users like or are looking for.

It collects demographic data, documents internet browsing behaviour, and notes the device you watch Netflix on and your streaming speed. According to its tech blog, Netflix uses machine learning and statistical modelling to make decisions related to content.

Additionally, Netflix researches pirated content to understand user streaming behaviour and what people like to view that is not available on streaming platforms, which fuelled its decision to stream Breaking Bad.

Challenging visual narratives

Currently, Netflix has around four million subscribers in the Middle East and North Africa. A survey estimates that over 60 percent of people in the 18-to-24 demographic watch pirated content in the Middle East and North Africa on laptops and mobiles.

In order to grow in the Middle East, Netflix would have attempted to target the audience that watches pirated content, such as Palestinian stories that are not widely available on mainstream networks.

It would have also found that existing Arab users are unable to find Palestinian content on Netflix.

Jenny McCabe, Netflix’s former vice-president of global brand communications, has said that while curating new content for Netflix, “We look for those titles that deliver the biggest viewership relative to the licensing cost.”

This implies that a perfect fit for deciding what to licence would be a film that is not too expensive but is watched by a lot of users for a long period.

Palestinian movies therefore likely provide a healthy balance of content that attracts user interest and comes with relatively low costs.

Deciding to stream Palestinian cinema is not the same as deciding to stream The Office or Friends, which everyone watches, resulting in a longer watch time for the platform.

The decision to stream Palestinian cinema could not just be a political decision about sharing Arab stories, but one that was informed by business and data analytics and aimed to grow Netflix in the Middle East through user acquisition.

In January 2022, social media platforms like Instagram and Twitter were replete with images and videos of the eviction of Palestinian families in the neighbourhood of Sheikh Jarrah in Jerusalem, to the extent that their algorithms made the protests against the occupation "trending".

In 2021, the writer Mohammed El-Kurd’s Instagram video on Sheikh Jarrah had over 500,000 views.

In the renewed interest in issues related to Palestine, Netflix responded to user search queries and interest by piloting the Oscar-winning short film The Present (2020) by Farah Nabulsi in March 2021, and got an insight through experimentation that the world is craving for Palestinian narratives.

This was an addition to Pomegranates and Myrrh (added in July 2021) and It Must Be Heaven (date of addition unclear).

The number of users who completed watching the existing titles motivated Netflix to stream a collection of 32 existing Palestinian movies in October this year.

This collection included Ave Maria (2015), an amusing short film focusing on Palestinian nuns who have taken an oath of silence and are accosted into helping an Israeli family that invades their church and decapitates the statue of Mary, and 3000 Nights (2015), which reveals the experiences of Palestinian women in Israeli prisons.

While Netflix had been streaming Israeli shows like Fouda since 2016, its decision to stream Palestinian movies heralded a new kind of visibility of the Palestinian condition.

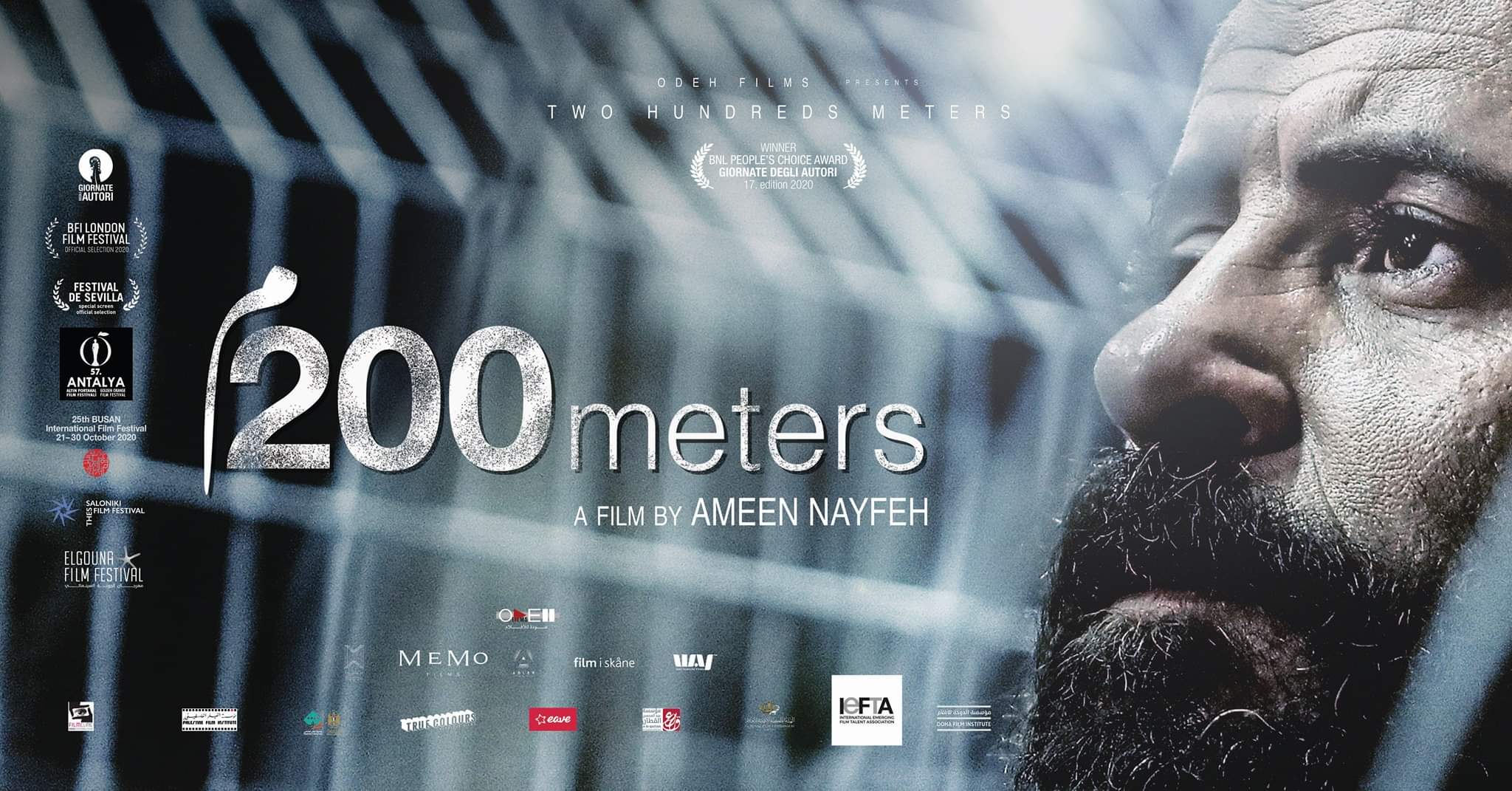

The audience would now be privy to the everyday rigmarole of Palestinians attempting to travel under occupation in 200m (2020), the absurd effects of bombing in the West Bank, like the assassination of a giraffe in a zoo in Giraffada (2013), and the traumatic effects of warfare and conditions of decrepit living in Born in Gaza (2014).

This visualisation would pave the way for the actor and comedian Mohammed Amer's eponymous Netflix Original Mo in August 2022, which reflects on the difficulty of being a Palestinian refugee seeking permanent residency in the US.

At a time when Facebook uses machine learning to censor Palestinian comments that are critical of Israel’s annexation practices and Google’s HR representatives allegedly ask employees not to talk about Palestine, Netflix courageously streaming Palestinian cinema is a breath of fresh air.

Palestinian stories make the Palestinian existence visible and help to combat Israel’s aggressive domination and erasure of Palestinian lives.

Being able to contribute to narratives surrounding their own existence helps Palestinians advocate for their cause. As the Palestinian academic Edward Said once said: “Facts do not at all speak for themselves, but require a socially acceptable narrative to absorb, sustain and circulate them.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.