Closing Guantanamo: Its victims deserve human dignity, not demonisation

The 11 January marks more than two decades since the opening of the Guantanamo Bay prison, where unlawful imprisonment, physical and psychological trauma - and US evasion of accountability - have become the norm.

The designation of the detainees as 'the worst of the worst' has continued to influence the conversation long after the accusations against the men were abandoned

In recent years, slow progress has been made to release and repatriate detainees. Yet despite the intention of three presidents to close the prison, 35 detainees continue to languish under horrific conditions.

Throughout the war on terror, Islamophobic narratives have been weaponised to initiate, sustain, and perpetuate violence against Muslims. These narratives set the terms on which wars are fought, who gets profiled and who doesn’t, who gets tortured and who doesn’t, and who gets to live and who doesn't.

Guantanamo Bay is one of the most notorious examples of how the public narrative has justified the detention, torture, and murder of Muslim men by constructing them as inherently terroristic and irredeemable.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

'The worst of the worst'

When the first 20 Muslim men and boys arrived at Guantanamo Bay in 2002, General Richard Myers, then chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, characterised them as "people who would gnaw through hydraulic lines at the back of a C-17 to bring it down".

Narratives such as Myers’s helped build the foundation for the demonisation of the men which was critical to justifying the torture and detention of the prison’s detainees.

In 2009, Dick Cheney referred to the 240 prisoners then at Guantanamo as "the worst of the worst", adding: "If you don't have a place where you can hold these people, the only other option is to kill them, and we don't operate that way."

The US does, however, operate this way, and the designation of the detainees as "the worst of the worst" has continued to influence the conversation long after the accusations against the men were abandoned; and even as calls for the closure of Guantanamo gained credibility over the years.

Years later, the special envoy for the closure of Guantanamo, Lee Wolosky, offered an explanation as to why it was difficult to transfer prisoners, insisting on the narrative of them being "the worst of the worst".

He stated: "The fact that they have been labelled in a political discourse as the worst of the worst, which some of them are, but some of them aren’t. And the ones we’re moving out are not, but they’re lumped in there [...] That certainly makes the task of doing what we do, which is looking at each case and convincing our foreign partners to look at the facts of each case, more difficult."

Wolosky chose not to attribute this particular construction to Cheney and instead feigned a sort of powerlessness as to how to disrupt this narrative - almost as though it had magically appeared, rather than being part of an intentional discursive strategy to legitimise state violence and keep the men behind bars.

The "worst of the worst" construction has had several iterations, including comments by Senator Tom Cotton, a Republican who has long supported Guantanamo’s operation.

During Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson’s nomination for Supreme Court Justice, he asked her: "Do you think most detainees at Guantanamo Bay were mostly terrorists or mostly, I don't know, innocent goat farmers"?

In an earlier interview on Fox News, he stated that the Muslim men detained were "not innocent goat herders". Cotton’s rhetorical strategy of juxtaposing two extremes - goat farmers against terrorists - was done to preclude any possibility of and, indeed, the absurdity of innocence - especially for those so deeply maligned and constructed as inherently terroristic.

Victim-blaming

Guantanamo detainees have been so thoroughly assigned guilt that when former President Trump gave his 2018 State of the Union address, he could still get away with maligning all the men who remained there.

He said: "When necessary, we must be able to detain and question [the detainees]. But we must be clear: terrorists are not merely criminals."

Just as important as these explicit narratives are the silent constructions. Nearly every year on the UN International Day in Support of Victims of Torture, the Bush, Obama, and Biden administrations have made statements condemning torture and reaffirming the US's commitment to supporting its survivors.

However, since the beginning of the war on terror and its institutionalisation of torture, the victims of US torture - in Guantanamo and elsewhere - have been entirely absent from the official discourse.

This lack of acknowledgment denies survivors the ability to be seen as victims, intentionally precluding the possibility that Guantanamo prisoners could ever be constructed as anything other than perpetrators, or a "special" kind of "criminal".

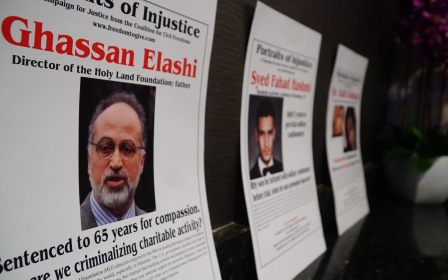

In other instances, narratives pleading for the transfer of the men detained at Guantanamo and the prison’s closure have minimised and disregarded their humanity altogether.

For example, in a New York Times op-ed, Wolosky urged Biden to close the prison. At the time, 40 prisoners remained at Guantanamo - 28 of whom, he said, could be transferred as "it’s hard to remember why some of them ended up in US custody [in the first place], or why they should remain there".

While the message is meant to be read as sympathetic and a call to end the atrocity that is Guantanamo, this language serves as a reminder that detainees’ lives are considered negligible and inconsequential by policymakers; so much so that they can continue to be imprisoned long after historical amnesia has set in.

In former President Bush’s catastrophic 2011 memoir, he asserted that while the opening of Guantanamo was necessary, he worked to close it because it "had become a propaganda tool for our enemies and a distraction for our allies".

Without commenting on the veracity, such discourse denies the men detained any semblance of humanity, and entrenches existing constructions of the “enemy” as inherently violent and motivated not by legitimate grievances, but by sheer hatred of the United States.

Muslims as 'enemy'

This discourse, far from being limited to the "enemy", has been uniformly imposed on those at Guantanamo and to Muslims in general.

Obama strategically echoed this line of argument for closing Guantanamo. In his final State of the Union address, he said he was committed to “working to shut down the prison at Guantanamo: it’s expensive, it’s unnecessary, and it only serves as a recruitment brochure for our enemies".

Statements like this fail to acknowledge what the "enemies" are responding to, namely, US state violence.

This sustained narrative cements the self-righteous notion that the only victim of Guantanamo is the US, not those who have languished behind bars for decades

Advancing the same rationale, a statement released by the Biden campaign in 2020 stated that he supported Guantanamo’s closure because it "undermines American national security by fuelling terrorist recruitment and is at odds with our values as a country".

This sustained narrative across administrations cements the self-righteous notion that the only victim of Guantanamo is the US, not those who have languished behind bars for decades.

Saifullah Paracha, the oldest detainee at 74, was repatriated to Pakistan in October after spending 18 years at Guantanamo, where he suffered from multiple illnesses, including diabetes and coronary artery disease.

The Department of Defence said in a statement that "[the continued] detention of Saifullah Paracha was no longer necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the US".

Despite serving nearly two decades in detention at Guantanamo without ever being charged with a crime, Paracha was not exonerated, nor did the Pentagon offer any explanation or apology for his prolonged detention.

In a letter to his attorney, Yemeni prisoner Adnan Latif, who was cleared for release several times before he died by suicide in 2012 while still in custody, wrote: "This is a prison that does not know humanity, and does not know [anything] except the language of power, oppression and humiliation for whoever enters it."

Closing Guantanamo is about more than simply emptying it of human bodies. These men have a right to human dignity and justice.

Going forward, advocates and policymakers must shift the conversation on closing Guantanamo towards language that rejects the power asymmetries, oppression, and humiliation that this discourse has long been rooted in.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.