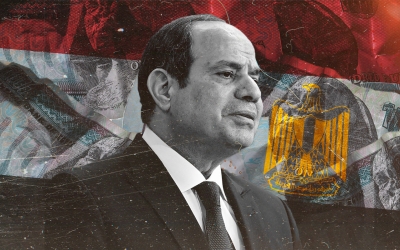

How IMF loans keep Sisi afloat as Egypt sinks deeper into debt

Egypt has agreed three bailouts with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) under the government of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, in office since 2014. It is currently the second biggest borrower from the IMF after Argentina.

The IMF deals came against the backdrop of a shortage in foreign currency and skyrocketing debts. Egypt's foreign debts rose from almost $40bn in 2012, to almost $155bn in 2022.

Apart from the support it has received from international financial institutions, including the IMF, the World Bank and the African Development Bank, Egypt has also received an estimated $92bn from Gulf countries in the past decade.

While Gulf deposits in Egypt in the two years after Sisi came to power boosted the country's foreign reserves, that support has gradually declined since 2015 as Egypt struggled to repay its debts and finance its import-dependent economy.

Increased borrowing also means that most of the government's expenditure has been dedicated to debt repayments rather than health, education and economic projects.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"The government should have channelled this spending to production projects that can generate revenues," Alia al-Mahdi, a professor of economics at Cairo University, told MEE. "Overspending on infrastructure projects has contributed to the financial crisis we suffer from now."

Ishac Diwan, a Lebanese economist and former senior World Bank official, said that "the combination of the IMF's stamp of approval, and very liquid international markets after 2016, have allowed Egypt to borrow a lot so as to delay necessary reforms".

"It now finds itself again with a very weak economy and a larger debt problem," he told MEE.

Last month, Egypt received the first tranche of the IMF's latest $3bn loan, which is intended to help it address the economic repercussions of the conflict in Ukraine.

The war has dried up Egypt's coffers and opened the door for possible unrest, with its economic toll hitting the pockets of poor and middle-class Egyptians.

Nevertheless, the IMF is imposing a set of stringent conditions on Cairo so that the lender could move ahead with the deal over the next 46 months.

The IMF says the conditions are necessary to preserve the stability of the overall economy and encourage private sector-led growth.

They also aim to produce a shift to a flexible exchange rate regime (in which the value of the currency is determined by supply and demand) and monetary policy, to reduce inflation and consolidate the country's debts.

But the resulting devaluation of the pound is exacerbating the woes of the majority of Egypt's 104 million population, with an estimated 60 million people living below or just above the poverty line.

The IMF loan also unlocks investments from Gulf countries worth $6.7bn in the next three fiscal years. GCC countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar have vowed to support Egypt with more than $20bn in deposits and investments.

Why Egypt continues to borrow from the IMF

A combination of internal structural problems and external factors have led to a shortage of foreign currency and spiralling debts. In addition to the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine there are other issues that have contributed to economic instability.

The IMF argues that Egypt's heavily managed exchange rate is a big part of the problem.

It says abrupt devaluations of the pound have led to hikes in inflation and reduced investor confidence. Accordingly, the main objective of IMF deals is to float the pound, which in turn would stabilise the supply and demand of foreign currency and preserve foreign reserves.

Another factor, also highlighted by the IMF, is the expansion under Sisi of privileged military-owned enterprises, which have crowded out the private sector and foreign investments. These entities operate largely without oversight and outside the official state budget.

Meanwhile, the military has overseen expensive mega-projects that have consumed the bulk of available revenues from both hot money (short-term investments in financial markets taking advantage of high interest rates) and international support.

These include the $58bn new administrative capital, massive arms purchases and the $8bn expansion of the Suez Canal - none of which have so far produced any economic benefit.

Against this backdrop, Egypt agreed in its latest programme to reduce the footprint of state-owned enterprises, including military-owned ones, and level the playing field with the private sector.

Moreover, the Sisi government has in recent years relied heavily on hot money during an era of unprecedentedly low interest rates and borrowing costs.

But that approach has proved unsustainable as external shocks such as the war in Ukraine led to the sudden flight of about $20bn in 2022.

Egypt's finance minister admitted his government had "learned its lesson" and would not depend on hot money again.

Below is a breakdown of the three deals agreed between the IMF and the government of President Sisi.

The First Loan: Extended Fund Facility

In November 2016, the IMF approved an Egyptian request for a $12bn loan under a three-year arrangement.

The Egyptian loan request came against a backdrop of persistent instability, terrorist attacks in the Sinai and elsewhere, weak tourism and factory closures due to energy shortages.

The arrangement aimed to help Egypt restore stability and promote growth.

'By giving Egypt money for one thing, the IMF in effect frees up other government funds to spend on things that the IMF might not support or approve of'

- Yezid Sayigh, Carnegie Middle East Centre

It required the government to adopt policies that sought to correct external imbalances and restore competitiveness, reduce the budget deficit and public debt, boost growth and create jobs while protecting vulnerable groups.

"The authorities recognise that resolute implementation of the policy package under the economic programme is essential to restore investor confidence, reduce inflation to single digits, rebuild international reserves, strengthen public finances and encourage private sector-led growth," said Christine Lagarde, then the managing director and chair of the IMF.

Funds in the EFF programme were deposited directly into the state budget but with no scrutiny of how the money would be spent. In a report, for example, the IMF mentions spending on health and education, but does not refer to any specific projects that would be launched by the Egyptian government.

In July 2017, the IMF Executive Board completed its first report on the progress of the $12bn arrangement - and gave it a positive review.

The board said the reform programme was off to a good start, citing the transition to a flexible exchange rate and the disappearance of the parallel foreign currency market. On the same day, Lagarde congratulated Egypt on the success of its "ambitious" programme.

But in September 2017, the IMF issued a staff report in which it referred to non-compliance by the Egyptian authorities with some terms of the deal, including a large depreciation of the Egyptian pound.

"The authorities failed in applying the conditions dictated by the IMF and other lending institutions," Egyptian economist Mamdouh al-Wali told Middle East Eye.

"This was why Egypt continued to suffer a financing gap, which kept the borrowing drive active," he said.

He estimated the amount of money Egypt borrowed from international institutions, banks and other countries at $16bn annually.

Nobody can speak with any degree of certainty about the way the $12bn acquired by Egypt from the IMF since 2016 has been spent, but many accuse the government of mismanaging these funds.

"There is no transparency or accountability in this government," Wali said. "This makes the structural problems of the Egyptian economy worse."

One problem, according to Yezid Sayigh, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Middle East Centre in Beirut, is that "money is fungible".

"By giving Egypt money for one thing, the IMF in effect frees up other government funds to spend on things that the IMF might not support or approve of," he told MEE.

Before getting the first tranche of the loan, Egypt devalued the pound at a cost of almost 48 percent of its value against the US dollar, the main import currency in the country.

The move, however, failed to reduce pressure on international reserves at the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE), amid reports of Egypt opting for a managed exchange rate regime.

International reserves at the CBE rose from $31.3bn in the 2016-2017 fiscal year to $44.5bn in the 2018-2019 fiscal year.

Nonetheless, this rise boiled down mainly to support from Gulf states which deposited billions of dollars (a total of $18.5bn in the 2016-2017 fiscal year, according to the CBE) in the central bank.

Policies adopted by Egyptian authorities, including the elimination of some subsidies, new taxes and a partial flotation of the pound, also caused a gradual decline in the deficit, pushing the growth rate up and contributing to reducing the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Covid crisis leads to two more loans

Covid-19 took a heavy toll on the Egyptian economy.

Tourism collapsed after authorities decided to suspend all incoming and outgoing flights at a cost of $1bn a month in lost revenues. It also caused the loss of tens of thousands of jobs in a sector that contributes 12 percent to Egypt's GDP and employs 10 percent of the workforce of 27 million.

A partial lockdown also slowed down production and caused job losses in the industrial sector, with Sisi appealing to investors and employers to keep their labour.

The government spent tens of billions of pounds to support the tourism, industrial and agricultural sectors, offering cash aid to hundreds of thousands of workers.

Spending on health also spiralled, with Egyptian state-run hospitals, which were overwhelmed at the peak of the pandemic, offering free treatment to patients.

This spending, including the purchase of vaccines, medicines and food, further increased pressure on Egypt's foreign reserves.

The foreign reserves had dropped to $37bn at the end of April 2020, down from $40bn at the end of March and more than $45bn at the beginning of that month.

Egypt also experienced capital outflows of nearly $16bn in the same year.

In order to finance the response to Covid, Egypt requested a further loan of $5.2bn from the IMF, which the latter approved in June 2020 in the form of a 12-month Stand-by Arrangement.

The lender said the programme would focus on addressing the immediate needs of the pandemic, including critical spending on health and social programmes to protect the most vulnerable.

But, once again, the IMF did not stipulate specific projects where the loan money would be spent.

In November of the same year, the IMF issued its first review report in which it said the Egyptian economy had performed better than expected, despite the pandemic.

It said containment measures, supported by the authorities' crisis management, and strong implementation of their policy programme, had helped mitigate the crisis. A final review in May 2021 also commended the Egyptian authorities' management of the programme.

A month before the Stand-by Arrangement, the IMF had also offered Cairo a credit facility of $2.7bn to help it overcome financial difficulties during the pandemic.

This financing, informed sources say, was instrumental in helping Cairo keep going, especially with the pandemic taking a heavy toll on the economy.

"The government used the loans in partly bridging the budget deficit and responding to financing needs," Ahmed Diab, a member of the Economic Committee in the Egyptian parliament, told MEE.

"Egyptian authorities would not have managed to get over the difficulties caused by the pandemic without this facility."

War in Ukraine: Egypt goes back to the IMF

Egypt turned again to the IMF in 2022 in the aftermath of the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war in the context of dwindling foreign currency reserves and soaring food and energy prices. The country depended on the two warring nations for the majority of its wheat supply and one third of tourists.

In October, Cairo agreed to a 46-month Extended Fund Facility with a series of tough terms for dispensing the different tranches of the loan.

The terms include a permanent shift to a flexible exchange rate regime, measures to reduce inflation and the public-debt-to-GDP ratio, and increased social spending to protect the vulnerable.

Cairo was also required to implement structural reforms to reduce the state footprint and encourage private-sector-led growth, and strengthen governance and transparency in the public sector.

Prior to the deal, the government had already pushed for the privatisation of some sectors of the economy, including through foreign investors, among other measures aimed at attracting some $40bn. Gulf countries have already acquired stakes in Egyptian companies as part of the privatisation drive, including fertiliser companies, hospitals and banks.

In a policy blueprint titled State Ownership Policy, the government laid out a plan to either partially or totally end state control over sectors such as port construction, fertiliser production and water desalination over the following three years.

But economists expect pushback against some of these policies by state institutions, especially the military which owns a huge business empire.

'Past experience suggests that the government will exploit every loophole to delay implementation of provisions of the IMF agreement'

- Yezid Sayigh

"Military resistance almost certainly explains the continuing delay in floating military companies on the stock exchange or selling shares through Egypt's sovereign wealth fund," Sayigh wrote in an article recently.

"Indeed, the military is known to be hostile to the sale of any state assets, let alone its own," he added.

Sayigh noted that this helped to explain opposition among parliamentarians to the government's plans to privatise companies and other assets belonging to the Suez Canal Authority, which the military regards as its exclusive economic enclave.

"Military opposition is significant, but past experience suggests that the government will exploit every loophole to delay implementation of provisions of the IMF agreement," Sayigh wrote.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.