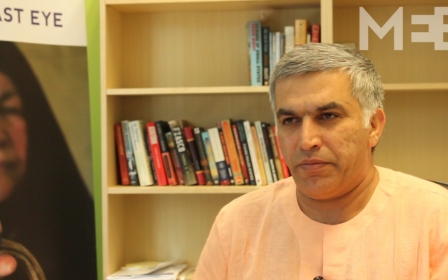

Bahraini human rights leader defiant ahead of sentencing

Nabeel Rajab has spent much of the last decade in prison, under house arrest, or banned from travelling.

As one of Bahrain’s most well-known human rights activists he has been a thorn in the side of the ruling al-Khalifa family, setting up the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights in 2002 along with other pro-democracy activists, including the currently imprisoned Abdulhadi Alkhawaja, and becoming a leading figure in the protests which have rocked the small Gulf nation since 2011.

“I have seen my children grow-up while I was in jail,” he told Middle East Eye. “I got used to it, although it is very ugly and bad to see your children growing up while in jail.”

On 1 October 2014, Rajab was again arrested, shortly after returning to Bahrain from a speaking tour of Europe, this time charged with “insulting a public institution and the army” allegedly over a tweet in which he suggested that security institutions could act as an “incubator” for the kind of sectarian ideology that generated the Islamic State (IS) organisation.

With the verdict in his trial due on 20 January, he could face 6 years in prison. Though far from relaxed by the prospect, he noted a certain irony in the amount of coverage his arrest had generated internationally.

“Every time they supress me and put me in jail, at the same time they make me more popular,” he told MEE via Skype.

“That’s the reality they are facing now!”

MEE had previously interviewed Rajab in August 2014, shortly after being released from jail having served 2 years for holding an “illegal gathering.” With such a short break between spells in jail, he doesn't relish the thought of returning again, nor the effect it would have on his family.

“Yes my kids are tense that again their father could spend time in jail,” he said. “But they are proud of me, of the work I do, of the struggle and of the support I have locally, regionally, internationally.”

His latest arrest provoked global outrage with numerous campaign organisations and charities calling for his release.

Sixteen NGOS, including Index on Censorship, Amnesty International, Freedom House and Human Rights Watch, signed a letter on Friday addressed to 47 states in the international community calling for pressure to be applied to drop the charges against Rajab.

“The charges levelled against Rajab are illegal under Bahrain’s commitments to the international community and international human rights law,” read the statement.

“Bahrain is party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), having acceded to the covenant in 2006. Article 19 of the ICCPR provides everyone with the fundamental rights to opinion and expression…by prosecuting Rajab for statements that he made over Twitter, the Bahraini government violates its own commitments to the international community.”

But the strong relationship between the small Gulf country and many more powerful Western countries has been pointed to as a block on any genuine reform. Bahrain is one of numerous regional countries to join the coalition against IS in Syria and Iraq (scores of Bahrainis have travelled to join the militant group) and a deal between Bahrain and the UK government to construct a new base naval base in the country has left some campaigners despondent.

"The charges against Nabeel are baseless and the Foreign Office should call for his release,” said Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, Director of Advocacy, Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy, in a statement on Friday.

“But it seems Bahrain has bought Britain's silence by building them a naval base in the Gulf."

Nabeel Rajab acknowledged that these new arrangements had bought the Bahraini government a windfall and guarded them against further pressure.

“Now they can receive less criticism from the international community, because they need them in the war against IS,” he said.

“They think this is the right time to continue the crackdown, without any criticism from the international community or Western governments, which is absolutely right and it’s happening.”

The arrest of Sheikh Ali Salman, secretary-general of al-Wefaq – Bahrain’s largest opposition party – sparked off a new wave of protests and has led to continuing worries about the shrinking possibility of any reform in the kingdom.

“Almost each and every Shiite family have one or two prisoners or someone who has been shot, injured or killed,” says Rajab. “So the gap is deeper, the wound is deeper than two or three years ago. And Bahrain is going towards more repression.”

“For the first time since the independence of the country [in 1971], we have a law in Manama saying that no peaceful protests are allowed altogether,” he added, also pointing out that protests outside the capital - while still legal - where also becoming intensely difficult to organise due to state repression.

Major fears have also arisen over the potential for a rise in sectarian militancy among the Sunni population amid growing sympathies for IS.

The government’s decision to import and naturalise thousands of people from countries such as Pakistan and Yemen – often alleged as a scheme to engineer a demographic change in the Shiite-majority nation – has further increased tensions.

“Bahrain's policy of recruiting Sunni police officers from Jordan, Pakistan, Syria, and Yemen, and granting them citizenship, has potential to lead to further penetration of Daesh [IS] influence within the state security apparatus,” wrote Giorgio Cafiero, research analyst with Country Risk Solutions, in the Huffington Post on Thursday.

“These ‘New Bahrainis,’ who were lured into joining the island Kingdom's security organizations by higher pay compared with what they made in their native countries, were hired by the government to protect the royal family's firm grip on power as Shiite unrest grew.

“Given that these ‘New Bahrainis’ are not native to Bahrain, there is a risk of their loyalty shifting from the monarchy to al-Baghdadi's ‘caliphate,’ which could create serious security implications for the country,” he warned.

Rajab told MEE that he agreed there was cause for concern over the rise of extreme sectarian groups in Bahrain who would view the country's Shiite population as "infidels" worthy of death.

“I still think extremism, fundamentalism, Islamist terrorist groups are becoming deep-rooted here and need to be discussed. It is a future threat in our country,” he said.

“We could face attacks – it’s a threat for the government and for the Shiites. And that should lead the government to think twice, to listen to their own people and compromise and have a political solution to the political crisis, before this terrorism becomes a real threat.”

Despite a potentially bleak future for Bahrain, along with concerns about the prospects for a wider conflagration in the Gulf as a result of the unrest in the small country, Rajab remained defiant that he could shoulder the consequences of Tuesday’s decision, whatever it may be.

“I am ready for all circumstances and my family also are ready for all circumstances. When I came to Bahrain, I knew I would be arrested, though the government denied they had a plan to do so,” he said.

“I’m willing to pay the price for the struggle – I hope nothing happens, but if anything happens it will not change my position and I will continue fighting for freedom, equality and democracy in country.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.