Knight Ridder: How a small team of US journalists got it right on Iraq

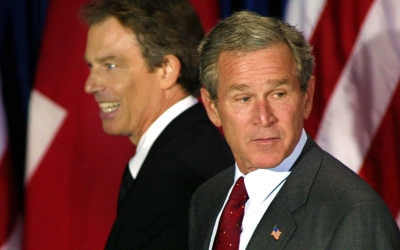

In the months leading up to the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, the American media landscape was awash with false reports linking Saddam Hussein to weapons of mass destruction.

That claim, like much of the Bush administration's justifications for the Iraq war, often went unchecked by the overwhelming majority of media organisations.

Except for one newspaper company.

The team covering Washington for Knight Ridder, a media company that merged with McClatchy in 2006, published dozens of articles in several newspapers criticising the intelligence being cited by mainstream US media at the time.

While their reporting couldn't sway public opinion against the invasion of Iraq, twenty years later, the reporters and editors are the subject of the Hollywood-produced documentary, Shock and Awe, directed by Rob Reiner, which chronicles the story of Knight Ridder's coverage.

"I don't want to say [our reporting] brought me satisfaction. It didn't. Because we still invaded. The cost, in lives and money, is just astronomical and we're still paying for it. We're still paying for the consequences of this invasion," said Jonathan Landay, one of the reporters who led Knight Ridder's coverage on Iraq.

Nor did their work strike a serious conversation in the US Congress about the war.

The 2002 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) passed through the House and Senate with little difficulty.

"Our job isn't to stop wars or to start wars, or to set American foreign policy. But I'll forever be disappointed that our reporting did not stir a real critical debate in Congress," said Warren Strobel, another Knight Ridder reporter who led their Iraq coverage.

Since the invasion in 2003, Brown University's Costs of War project estimates the direct death toll in Iraq, and later in Syria, to be between 550,000 to 580,000 people.

Knight Ridder news

Knight Ridder's coverage in the lead-up to the Iraq war was led by John Walcott, Jonathan Landay, Warren Strobel, and Joe Galloway, who passed away in August 2021.

Walcott, who served as the Washington news editor and later bureau chief from 1999-2006, said many of the towns and cities in the US where Knight Ridder had a strong readership were military towns.

As a result, their outlook on news coverage related to wars can be summed up in a line Walcott stated in the film Shock and Awe, which Walcott, Strobel, and Landay said was based on a real conversation in the newsroom.

"We don't write for people who send other people's kids to war. We write for people whose kids get sent to war," Walcott, played by Reiner, was depicted as saying.

Their coverage exposed holes in the US intelligence against Iraq's then-leader Saddam Hussein as early as 2001.

'We don't write for people who send other people's kids to war. We write for people whose kids get sent to war'

- John Walcott, Washington editor at Knight Ridder

"Very soon after the 9/11 attacks, I found out that the Bush administration was considering not just Afghanistan, but also looking at Iraq in terms of military and diplomatic options," Strobel said.

"This is long before they started making the case for war, but just the very fact that they were considering Iraq as a potential target made no sense to me."

What set them apart, according to Walcott, was that the reporters had an extensive network of sources inside the lower and mid-levels of the US military and intelligence apparatus. The links date back to the days of the Vietnam War, according to Walcott.

So rather than relying on the official line toed by top American officials, like other newspapers were doing at the time, Landay, Strobel, and Galloway were able to speak with officials that were more insulated from the politics of national security.

"The value of a source is more often inversely proportional to their rank, rather than directly proportional. The higher you go up the ladder, the more politicised the sources become, understandably so - their job is sales, not research," Walcott said.

"I think there were a lot of reporters who liked to run in those circles. They want to be invited to the right parties. They really want to be part of the first estate, not stand outside and be part of the fourth estate."

This was a part of the problem, Walcott noted. Much of the press corps in Washington at the time was relying on high-level officials in the Bush administration, and failed to push back against their claims or even at times to fact-check.

Debunking intelligence

Between 2001 and 2004, the team of Walcott, Strobel, Landay and Galloway published more than 80 stories related to faulty intelligence on Iraq. The articles are currently available at McClatchy (under a paywall).

The reports included debunking the infamous aluminium tubes intel, in which the Bush administration had stated that Hussein was purchasing thousands of aluminium tubes for the purposes of creating centrifuges and ultimately a nuclear weapon.

Landay wrote a story citing a CIA report that disputed this and instead said the aluminium tubes were likely meant for conventional weapons, not a nuclear bomb.

Landay said he had several favourite stories from that time, including one revealing how the Iraqi National Congress (INC), an Iraqi exiled group, fed false reports and intelligence to numerous western newspapers.

One such report was published by the New York Times and was based on an interview with an Iraqi defector who claimed he had visited 20 sites in Iraq associated with a biological weapons programme, adding that there were labs under two presidential sites in residential areas.

"Who puts a bioweapons lab under their home?" Landay wondered when he saw that report.

It turned out that the defector was coached into saying these things and was even trained to pass a polygraph lie detector test.

"I won't even call it intelligence because it wasn't intelligence. And this stuff was leaked deliberately to The New York Times and other news organisations by an administration that was eager to gin up public support for an invasion," Landay said of the information fed to both US officials and the news media by the INC.

One of Strobel's favourite reports was a story he did with Walcott in February 2002, citing several officials that said Bush had decided "Saddam had to go".

"That story got a lot of attention. We got angry emails from people saying we've given away the president's plans and put American lives at risk, which of course is ridiculous. I'm proud of that story," Strobel said.

By the end of 2002 alone, the team had published more than a dozen stories pushing back against the faulty intelligence being used to justify the war.

"One by one, almost every argument they made to justify invading Iraq just either fell apart or didn't hold water," Walcott said.

Yet even though they had done intense, well-researched stories that bucked the mainstream media's coverage, they at times struggled to have their stories read by the public.

Some of their own newspapers wouldn't publish their stories, citing that the information they had wasn't in The New York Times or the Washington Post.

"We probably had greater resources than anyone else. What we didn't have the ability to do - and it's probably right that we didn't - is to tell the newspapers what to print. And so there was a constant struggle going on with newspapers wanting to run with the New York Times," Walcott said.

"There was one editor's meeting I remember at San Jose, when the editor of a fairly prominent newspaper said 'that's the New York Times'," the editor recalled. "'We have to run that'."

The New York Times did get it wrong, and on 26 May 2004, the editorial page published a note to editors, in which it outlined in detail the various stories that were "not as rigorous as it should have been".

Middle East Eye reached out to The New York Times for an interview regarding its coverage leading up to the Iraq War, but the newspaper said no one was available for an interview and referred to its 2004 editor's note.

Incredibly lonely

This period in time was "incredibly lonely", as both Strobel and Landay described it.

"As journalists, you want to be out there in front with a scoop or with a story or with a fresh take on a story," Strobel said.

"But you also want to look behind you and see that others are racing to catch up. We looked behind us and nobody was racing to catch up."

Landay recalled that sometimes he would wake up in the middle of the night wondering whether what he was reporting was right.

'Why isn't anyone else reporting what we're reporting?'

- Jonathan Landay, reporter at Knight Ridder

"Are we accurate? Why isn't anyone else reporting what we're reporting?" he wondered on those nights.

Few voices in Washington, at the time, were critical of the war, and several figures in the mainstream media who were critical found themselves no longer employed.

There were some people in the administration as well as members of the press, however, that were supporting their work and cheering them on, albeit in private.

"The rest of the press mostly left us alone. There were some people at other news organisations who quietly cheered us on because their organisations weren't doing what we were doing," Walcott added.

But aside from the silent support, they received a lot of hate, and their reporting had also led to a death threat that was sent to the newsroom, which Landay said didn't do anything to stop their work.

"That really never caused us to pause or dissuaded us from pursuing the journalism that we did, it was journalism. It was our job," Landay said.

'Just do journalism'

Sitting in the Edward B Bunn Intercultural Center at Georgetown University in Washington, Walcott said that he has very few regrets from his time covering the lead-up to the war.

Looking back at his time at Knight Ridder, Walcott said his only regret was not getting to break the story of Curveball, the name given to a now-discredited Iraqi defector who had provided information that was the basis for Bush's claims that Hussein "built a fleet of trucks and railroad cars to produce anthrax and other deadly germs".

He continues to teach at Georgetown and has assigned his students this semester to watch the 2017 film Shock and Awe.

Since his team's coverage of Iraq in the early 2000s, Knight Ridder has been bought by the publishing company McClatchy. Walcott went on to work for McClatchy for a number of years before moving on to other news companies.

Landay stayed on at McClatchy for nearly a decade before moving to Reuters, where he works in a similar role as national security correspondent. Stroebel is now at the Wall Street Journal, where he is a national security reporter. Galloway died on 18 August 2021.

Besides The New York Times' editor's note in 2004, there has been little public apology from American media for their coverage leading up to the Iraq War.

Walcott noted that Knight Ridder's own newspapers haven't issued any apology and he wasn't expecting them to make one anytime soon.

"The New York Times to its credit, apologised. But I don't recall any of our newspapers apologising to me or anyone else. That would be painful, I understand."

The three journalists have stayed in touch throughout the years, and Strobel and Landay continue to work in the field of national security reporting, where they say that the lessons of the Iraq war coverage are still relevant today.

"A national crisis is no time to lose your head or lose your bearings," said Strobel.

Strobel noted that reporters should continue to be skeptical, pointing to today's cases of fear over a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, as well as the reports of Iran's nuclear programme.

"Just do journalism. Ask the right questions. Don't accept what the government tells you at face value, which is what was happening on the part of virtually all of the media in the run-up to the war in Iraq," said Landay.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.