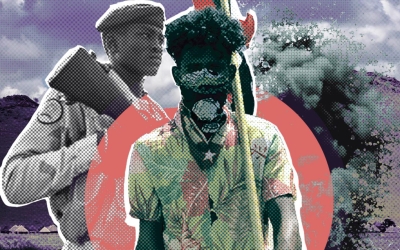

Sudan simmers as Burhan-Hemeti rivalry threatens to boil over

The power struggle between Sudan’s de facto head of state General Abdul Fattah al-Burhan and his deputy Mohamed Hamdan Daglo, chief of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) militia, has become unstoppable, threatening the overall security situation in the country, according to military and diplomatic sources.

Military and civilian analysts, as well as western diplomats, told Middle East Eye there are more and more signs of escalation amid attempts at mediation between the two sides.

Burhan and Daglo, who is better known as Hemeti, have maintained an uneasy alliance since the October 2021 coup led by Burhan, which saw the military replace Sudan’s transitional civilian-led government. But both men have different sources of power and wealth, as well as different international sponsors.

As head of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), Burhan controls a significant military-industrial complex. He is also favoured by Egypt, Sudan’s neighbour, and by Islamist figures who held power in the days of longtime autocrat Omar al-Bashir, who was removed from power in 2019.

Hemeti, who was once head of the notorious Janjaweed militias in Darfur, controls gold mines in the troubled region and has influential supporters in the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Both Burhan and Hemeti have met with high-level members of the US, Russian and Israeli governments, with Hemeti in Moscow when Russia invaded Ukraine.

In the meantime, international mediators between civilian and military representatives insisted that the different stakeholders will sign a final agreement by the middle of April at the latest. The framework agreement will include a new constitution and will form the basis for a new civilian-led government.

'On the whole, Burhan and Hemeti do not share a common vision for the consolidation of their joint coup in 2021'

- Kholood Khair, Sudanese analyst

The deal is thought to favour Hemeti, which is one reason why the RSF chief has been publicly supporting it. A draft of the final agreement seen by MEE calls for the integration of the SAF and RSF – in addition to former rebel movements – to be agreed within ten years.

A workshop between civilian, military and RSF representatives ended on Wednesday without reaching any final recommendations, as differences over the integration of paramilitary forces hardened and the army delegation withdrew suddenly from the closing session.

Resistance committees, which have been at the heart of Sudan’s ongoing democratic revolution for many years, continue to oppose the deal. Khalid Mahmoud, a resistance committee member, told MEE it would not achieve any political or security stability.

Analysts told MEE that, with many issues still unresolved, it was unlikely an agreement would be struck by mid-April.

Conflict signs

The people of Khartoum have woken up every morning to different signs of tension between the military and the RSF. The situation has led many to become concerned that there will be direct confrontations between the two sets of fighters.

Over the past weeks, intensive redeployment of forces and new security measures - including the building of new high walls - have been seen around the army headquarters in Khartoum. Bridges have been closed and opened by the military without any clear reason being given.

Tough security checkpoints are operating across the Sudanese capital and the inspection of travellers arriving at Khartoum airport has intensified.

Senior officials from both the army and the RSF have intensified their public rhetoric, as Hemeti and Burhan each jockey for regional and international support.

In January, Burhan visited Chad. The next day, Hemeti arrived in the same country. Two days after that, Israeli Foreign Minister Eli Cohen arrived in Khartoum, with Hemeti saying he had not been told about the visit.

In February, following the devastating earthquakes that hit Turkey and Syria, the SAF sent a plane of humanitarian assistance to Turkey. A week later, the RSF sent its own, separate plane.

In March, the rivalry escalated, with Burhan calling for the RSF to be integrated into the military. Hemeti responded defiantly, saying that he regretted the October 2021 coup he had helped bring about with Burhan.

Reintegration of the RSF

The issue of RSF reintegration has ignited the situation, with army general and Sovereign Council member Shams Aldin Kabashi saying openly that there was no way for Sudan to have two armies and that, as such, the RSF would have to be brought into the army’s fold.

A few days later, Abdul Rahim Daglo, Hemeti’s most powerful brother, implied that it was time for the army to hand power over to the Sudanese people.

Western envoys in Sudan, in addition to Saudi Arabia, the UAE and the Forces for Freedom and Change civilian coalition (FFC), have led mediation between the two sides of the military.

A western diplomat, who preferred not to be named, told MEE that talks were still ongoing as the two sides disagreed about how to integrate the RSF, the timeframe for this and other technicalities.

Another area of dispute is the influence and presence in the army of Islamist powerbrokers from the Bashir era. Hemeti has insisted that this issue is tackled, while army representatives deny Islamist influence within the SAF.

Burhan is reportedly intent on forming what he calls a “Higher Army Council”, a happy side-effect of which would be the removal of Hemeti from his post as deputy leader of the country.

The political process

A source close to the FFC said that the civilian coalition and Hemeti both support the framework agreement and want to see a final deal struck by the middle of April. The source accused the military of spoiling the agreement and supporting a coalition that includes two former rebel movements that rejected the deal.

Those rebel movements are the SLM-MN, headed by Darfur ruler Minni Minnawi; and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), headed by the current finance minister Gibril Ibrahim.

That final agreement aims to put an end to the military coup regime, see the withdrawal of the military from politics, and empower civilian control of the executive and legislative under a sovereign civilian entity.

Security agencies would be represented by a national security and intelligence council chaired by the prime minister.

But other important issues have yet to be addressed properly, including army reformation, transitional justice, dismantling of the former regime, the revision of the Juba Peace Agreement with rebel movements, and the crisis in eastern Sudan, where local groups have taken control of the country’s ports and are demanding more autonomy.

Russia and the West

The internal power struggle is complemented and augmented by a great power competition between Russia and the West, as well as the involvement of the Gulf kingdoms and Egypt.

MEE has established the presence of Wagner Group mercenaries in Sudan as well as neighbouring Central African Republic, while gold and other resources are being exported to Russia to aid Moscow’s war effort in Ukraine.

A political analyst, who asked not to be named, told MEE that the RSF was standing with Russia in Sudan and CAR, while the army was backing the West, including the US and European countries.

The analyst said western countries had put the expulsion of Russian mercenaries and gold companies from Sudan, CAR and Libya at the top of their list of political priorities, and were more interested in that than in the political process in Sudan.

Sudan’s military intelligence forces have arrested or summoned about 60 Russians and accused them of smuggling gold from the River Nile State.

The head of Al-Sulaj company, which in 2021 took over the Sudanese operations of the US-sanctioned Meroe Gold, told MEE that his company had been targeted as part of western attempts to contain Russian investments.

“We are working very legally and are very committed to Sudanese regulations of the business, so these actions are against the Russian interests,” Riad Alfatih said.

Hemeti's old rival

A further element in the struggle between Burhan and Hemeti emerged when the Sudanese military agreed a deal with eight Darfuri movements as part of negotiations sponsored by Qatar.

Included among these groups was Musa Hilal, a former Janjaweed leader who was arrested by his bitter rival Hemeti in 2017 during the days of Bashir. Bashir confiscated Hilal's gold mines in North Darfur and gave them to the RSF commander.

Hilal, who has been accused – like Hemeti – of human rights abuses in Darfur, was released from a Khartoum prison in March 2021. A former rebel leader told MEE that the release of Hemeti’s tribal leader was a move by the army to put pressure on him. The army recently denied recruiting Hilal’s fighters.

Middle East Eye contacted the military and the RSF but got no response.

Conflict and rapprochement

Kholood Khair, a Khartoum-based analyst, told MEE that tensions between Burhan and Hemeti are genuine, but that the two military leaders are also weaponising those tensions as a way of getting concessions from the civilians. This is something regional allies cannot contain.

“They allow their tensions to escalate, to increase their arms and their troops, in order to use the pressure of a possible confrontation to gain concessions from pro-democracy actors, particularly the FFC-CC. They then allow those tensions to dissipate, but maintain the concessions, the troops and the arms,” Khair said.

This dance of heightened tensions followed by rapprochement is becoming harder to pull off.

'It is unlikely that there will be a resolution of Burhan and Hemeti’s issues, especially not before the 1 April deadline'

- Kholood Khair, analyst

“It is unlikely that there will be a resolution of Burhan and Hemeti’s issues, especially not before the 1 April deadline. The worry is that a final agreement will be signed without any of these central issues being sufficiently addressed, thus booby-trapping a future government,” she told MEE.

“Furthermore, the Burhan-Hemeti relationship cannot be understood without including the Islamists. Whenever the relationship is stable, the Islamists work to undermine it. When the relationship is tense, they work to stoke the tensions,” Khair, who is the director of the think tank Confluence Advisory, said.

The Sudan Transparency and Policy Tracker (STPT) think tank has found that a party of former Bashir agents are behind the scenes working to ignite the situation.

Social media accounts manipulated by suspected former Bashir loyalists have sought to spread misinformation that enflames division between the SAF and RSF, as well as undermining civilian movements.

“On the whole, Burhan and Hemeti do not share a common vision for the consolidation of their joint coup in 2021,” Khair told MEE.

“Burhan seems to be pressing for the Egyptian scenario where elections would rubber stamp and legitimise his rule, while Hemeti is open to a UAE-style model that centres service delivery to gain legitimacy in a new social contract. Both these scenarios would likely be underwritten by an entrenched securocratic state using violence to achieve them," Khair said.

The Russia-West tensions are playing a role in this, but due to Sudan's proximity to the Francophone Sahel and Paris's competition with Moscow, it started a lot earlier than the invasion of Ukraine, Khair said.

“Since the invasion of Ukraine, the US has been the major foil for Russian involvement in Sudan's economy and politics, helped by its full diplomatic presence since August 2022.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.