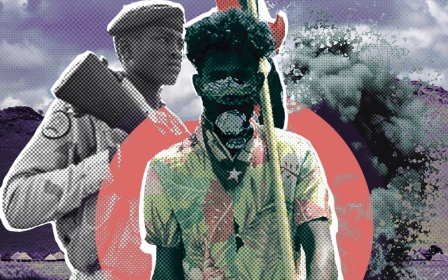

Sudan transition deal stalls again as military delays and holds onto power

Sudan’s journey to democratic rule has been held up again after the signing of an agreement to name a Sudanese civilian government and launch a new transition toward elections was delayed for a second time on Wednesday.

In a statement, Sudan’s Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) coalition, which has been representing civilians in internationally mediated talks with Sudan’s military, said that discussions on military restructuring had made progress but not concluded.

This has led to a delay in signing the deal, which was originally scheduled for 1 April, before being rescheduled for Thursday. The FFC did not say when the new signing date would be.

Civilian and military representatives have now twice failed to meet in order to sign a deal that finalises the details of power-sharing between the two sides, with the military accused of delaying tactics.

An ongoing cause of disagreement has been the integration of the powerful Rapid Support Forces (RSF) militia into the country’s military, a move called for in a framework deal for the new transition signed in December.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) want the process of integration to take two years, while the RSF wants it to take ten years. There are also issues regarding the role of a united military commander once the forces are integrated.

“Why the delays? I think because the security sector reform issues are the hardest and most intractable issues and they’ve saved those for the end,” Cameron Hudson, former CIA analyst and senior associate at the CSIS Africa Program, told Middle East Eye.

'Ever since Bashir fell four years ago this month, the military has successfully kicked the can down the road in order to maintain power'

- Kholood Khair, Sudanese analyst

“And it’s not just about the timeline to integrate the RSF. There are dozens of nettlesome issues covering everything from command and control to salaries and ranks that they have not even started to discuss,” Hudson said.

“Security sector reform is the transition, that’s why the other issues – though all interrelated – could be reasonably addressed while security sector reform has seen rivalries take centre stage, causing the delays,” Kholood Khair, director of Khartoum-based think tank Confluence Advisory, told MEE.

“Ever since Omar al-Bashir fell four years ago this month, the military has successfully kicked the can down the road in order to maintain power,” Khair said.

For Hudson, the deadlines being set are “totally arbitrary and unrealistic and have no basis in the substance of the questions that have to be resolved. In a normal world, we would be months away from a deal, not days.”

The military's tight grip

A democratic uprising brought an end to the three-decade-long rule of the autocrat Omar al-Bashir in 2019. But the transition toward full civilian rule in Sudan was brought crashing to a halt in October 2021 by a military coup led by army commander General Abdul Fattah al-Burhan and his deputy Mohamed Hamdan Daglo, who is the RSF’s chief.

Since then, the Sudanese people, spearheaded by the revolutionary resistance committees, have kept coming out onto the streets in protest against military rule. Sudan’s security and military forces have deployed rocket-propelled grenades, “dushka” mounted guns, tear gas, machetes, and stun grenades as part of their repression of these protests.

Civilian representatives are now split over the deal to transition Sudan away from all-out military rule, with the resistance committees, together with the Sudanese Communist Party, deeply critical of the December framework deal, which has also met with widespread anger on the streets.

For the resistance committees, there are three lines that can’t be crossed, or rather three noes: no negotiation with the military, no power-sharing with the military, and no legitimising the military.

Delays in the signing of the deal and disagreements over the integration of the RSF, among other things, are exacerbated by the personal rivalry between SAF commander and Sudanese de facto head of state General Abdul Burhan Fattah al-Burhan and his deputy Mohamed Hamdan Daglo, chief of the RSF.

Military and diplomatic sources told Middle East Eye last week that the struggle between the two men has become unstoppable and is threatening the overall security situation in the country.

Burhan and Daglo, who is better known as Hemeti, have maintained an uneasy alliance since the October 2021 coup led by Burhan, which saw the military replace Sudan’s transitional civilian-led government. But both men have different sources of power and wealth, as well as different international sponsors.

As head of the SAF, Burhan controls a significant military-industrial complex. He is also favoured by Egypt, Sudan’s neighbour, and by Islamist figures who held power in the days of longtime autocrat Omar al-Bashir, who was removed from power in 2019.

Hemeti, who was once head of the notorious Janjaweed militias in Darfur, controls gold mines in the troubled region and has influential supporters in the UAE and Saudi Arabia. The as-yet-unsigned deal is thought to favour him, which is one of the reasons why he has been publicly supporting it.

Each man is running a parallel foreign policy, taking high-level meetings of their own with regional and international governments, including the United States, Russia, and Israel.

A convenient rivalry

The threat of escalation between the army and the RSF has also been used by both Burhan and Hemeti as a way of getting concessions from the civilian population.

“They allow their tensions to escalate, to increase their arms and their troops, in order to use the pressure of a possible confrontation to gain concessions from pro-democracy actors… They then allow those tensions to dissipate, but maintain the concessions, the troops, and the arms,” Khair told MEE.

“The space created by the delays, full of uncertainty, instability, and competition – see the scaling up of RSF and SAF soldiers – is where Burhan’s Islamist backers thrive,” she said.

The presence of Islamist powerbrokers from the Bashir era has been an area of dispute. Hemeti has insisted that this issue is tackled, while army representatives deny Islamist influence within the SAF.

“If Burhan conceded too much on the deal, he becomes increasingly expendable. As head of the SAF, he is actually pretty vulnerable to removal.

"Part of the reason for delays, then, is Burhan wanting to buy himself time so that his generals will concede to keep him on,” Khair said.

The head of Khartoum's Native Administration had called for the closure of Sudan's capital on 5 April, meaning that street protests would not have been able to take place the next day. This was seen as being done at the behest of Burhan's Islamist backers. But the tribal head then had a stroke and could not put his plan into action.

For Hudson, the personal rivalry between Hemeti and Burhan is secondary to the "broader interests of the institutions they represent." This is "especially true of Burhan and the SAF", which is influenced by hardline Islamist elements and by neighbouring Egypt, whose President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi is a key ally of Burhan's.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.