Sudan: How an RSF attack on Burhan set the tone for a bitter conflict

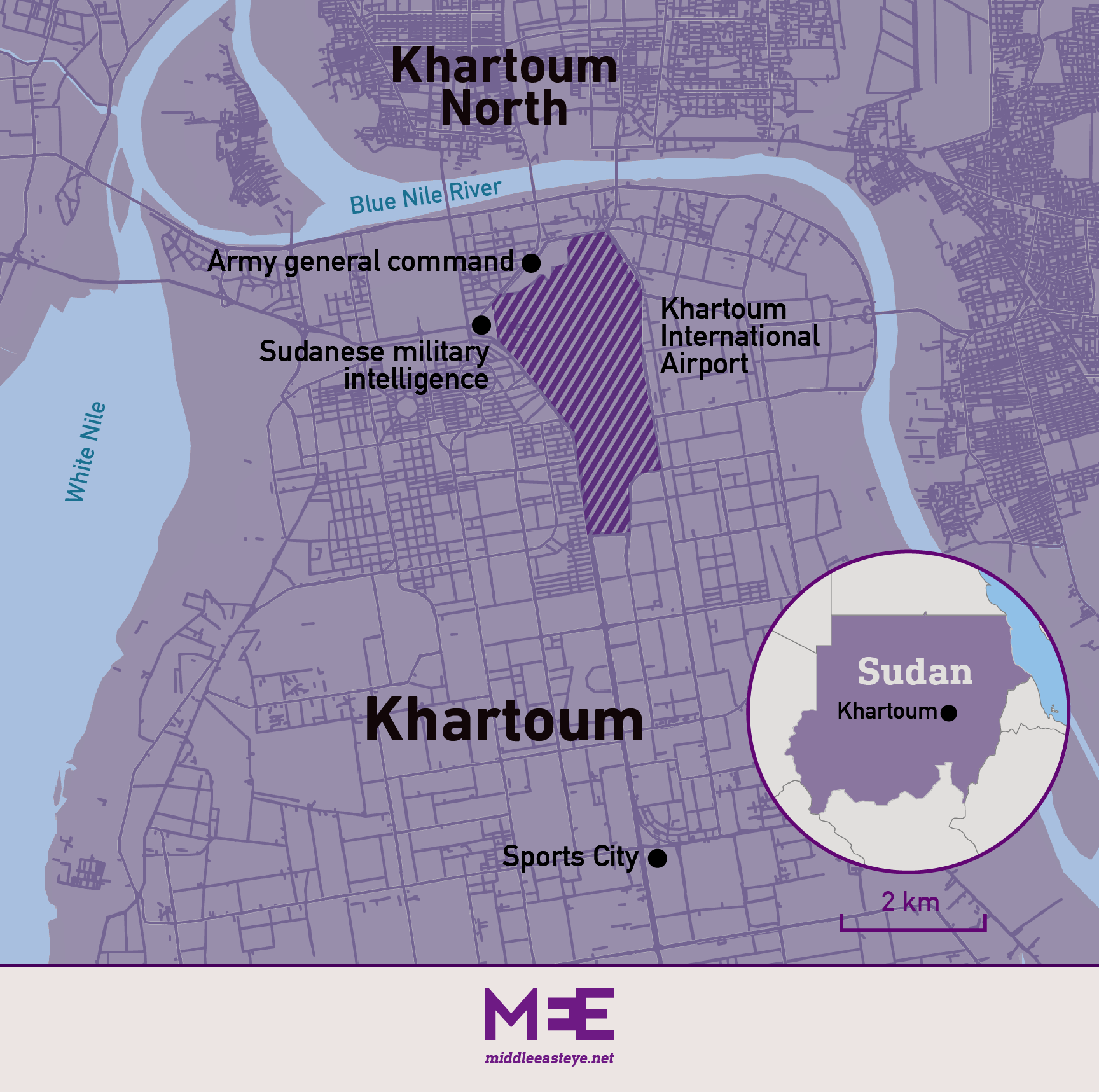

In the early hours of 15 April, some 2,000 paramilitary fighters moved quickly through Khartoum’s streets towards the headquarters of the Sudanese armed forces.

Inside was the residence of army chief General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, arch rival of the Rapid Support Forces fighters’ leader, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo. Suddenly Burhan’s house was under attack.

Sudanese sources close to the military described to Middle East Eye how the RSF approached the general command headquarters from a neighbourhood near the airport at 8.50 am, carrying an array of weapons of all calibres.

Attacking from three directions, the RSF launched an assault on Burhan’s residence, killing 35 members of the presidential guard in the process, the sources said. Burhan, who is Sudan’s de facto head of state, was at home at the time, and narrowly escaped capture - or worse. MEE has asked the RSF for comment.

It was a raid that set the tone for a conflict between Burhan’s military and the RSF of Dagalo, the rival general commonly known as Hemeti, a war that has raged for two weeks without indication the two sides could possibly come together. Soon after the attack on his home, Hemeti said Burhan would be captured or “die like a dog”.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“It was a coup attempt by Hemeti and the RSF. They tried to seize power," a Sudanese official loyal to Burhan told MEE.

Sources in Sudan, the United States, Israel, Egypt and elsewhere spoke to Middle East Eye about the first hours of the fighting - adding previously unreported details on the fraught build-up to the conflict, when both the army and the paramilitary were preparing for the struggle to come.

The assault on Burhan’s residence was a crucial early moment in a series of battles that raged in the Khartoum district around the airport and other key buildings, including the offices of the intelligence services and Hemeti’s own residence.

As Sudan’s de facto deputy leader, Hemeti has been living in the residence previously reserved for the vice president. From this building, the paramilitary leader had direct access to the army headquarters and Burhan's residence, as well as to the other official buildings around him.

RSF fighters, who are believed to now number between 85,000-100,000 overall, were already embedded in the district and easily able to launch their assault.

The general command headquarters, which is divided into separate buildings for its different divisions, including the air force, is connected by a series of gates. Paramilitary fighters seized the gates to the ground forces building in the early exchanges and burnt them to the ground, sources close to the army told MEE.

On the same morning, fighting broke out at the Soba military camp south of Khartoum and in Sports City, where the RSF has a base. An adviser to Hemeti told Reuters that RSF fighters at Soba were woken by army attacks on that morning.

Eyewitnesses in Khartoum told MEE that the first shots were fired in Soba and then Sports City, while sources close to the army insisted that the fighting began at the airport before moving to the general command headquarters.

Video footage reviewed by MEE shows Sudanese armed forces vehicles manoeuvring at Soba, close to Sports City, at 9.20am.

A breakdown in relations

Though we cannot yet say for certain who fired the first bullet, what is clear is that tensions had been building for some time.

Hemeti was moving RSF fighters in their thousands into strategic locations around Khartoum and to the air base in Merowe, about 330km north of the capital.

"For a number of months, Hemeti looked to establish the RSF around Sudan's five main military airports," the Sudanese official said.

The paramilitary group’s deployment of anti-aircraft guns in strategic and urban areas also unnerved the army. Over the past two weeks, those same weapons have been used on enemies in the air and on the ground.

The army was tracking these deployments and preparing to respond, sources close to the military told MEE.

Burhan and Hemeti were also in touch and had agreed to meet in person on 15 April, the day the fighting began. That meeting never took place, but a week before, on 8 April, they reportedly sat down together at a farm on the outskirts of Khartoum.

According to Sudanese officials, Burhan asked Hemeti to move RSF troops out of Khartoum. Hemeti in turn asked Burhan to order the withdrawal of Egyptian troops from Merowe, fearing the army chief’s close ally Egypt would use its military against him. Neither general would budge.

"Hemeti had been disobeying the chain of command for two years," a second Sudanese official working with the armed forces said. "There was some frustration within the army at Burhan's failure to act and stop this."

Eventually, RSF forces would capture Merowe air base and detained 27 Egyptian troops, before handing them over to Cairo under intense pressure.

An Egyptian military source told MEE that Egyptian pilots have been flying Sudanese air force warplanes throughout the conflict, conducting air strikes on the RSF on behalf of the army. The official close to the Sudanese army denied this.

Gold disguised as cookies

Burhan and Hemeti together led a 2021 coup that removed Sudan’s pro-democracy transitional civilian government, which had been in place since the fall of longtime autocrat Omar al-Bashir in April 2019.

Their relationship began to break down soon after they took power. In the months leading up to the outbreak of hostilities, the prospect of a western-mediated political deal that would have folded the RSF into the regular military spiked tensions to a new degree.

"Mediators operating in Khartoum realised they made a massive blunder by offering this integration of the RSF," Ehud Yaari, an adviser to the Israeli government on Sudan, told MEE. "This is what ignited the clashes."

Cameron Hudson, a former CIA analyst and Sudan expert, said: "The RSF was moving troops and equipment into and around Khartoum and that this was a driving factor in Sudanese armed forces thinking."

Troop movements were followed by high walls being erected around key buildings, which would eventually come under fire.

Adding to those tensions, according to a western official, was the seizure in March of large quantities of gold disguised as cookies on a Russian flight at Khartoum airport.

Hemeti and his family own a gold mining company that operates on lands he seized in Darfur, in western Sudan, in 2017. He has talked openly about not being the “first man to own goldmines”, but along with his fighters, the mines provide him with a key source of power and wealth.

He is also believed to help supply Russia with gold, assisting Moscow’s efforts to keep its economy afloat in the face of western sanctions meted out over the invasion of Ukraine.

"Hemeti has been involved in the gold trade for years," the first Sudanese official said. "He has accumulated money in many different banking systems, not just in the UAE."

According to the western official, an estimated 32.7 tonnes of gold was smuggled out of Sudan on 16 charter flights with an estimated value of $1.9bn between February 2022 to February 2023. The cargo was always labelled as cookies, the official said.

The official said there was an attempt by RSF fighters to seize the gold from authorities hours before hostilities broke out.

Additional reporting by Mohammed Amin and Suadad al-Salhy.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.