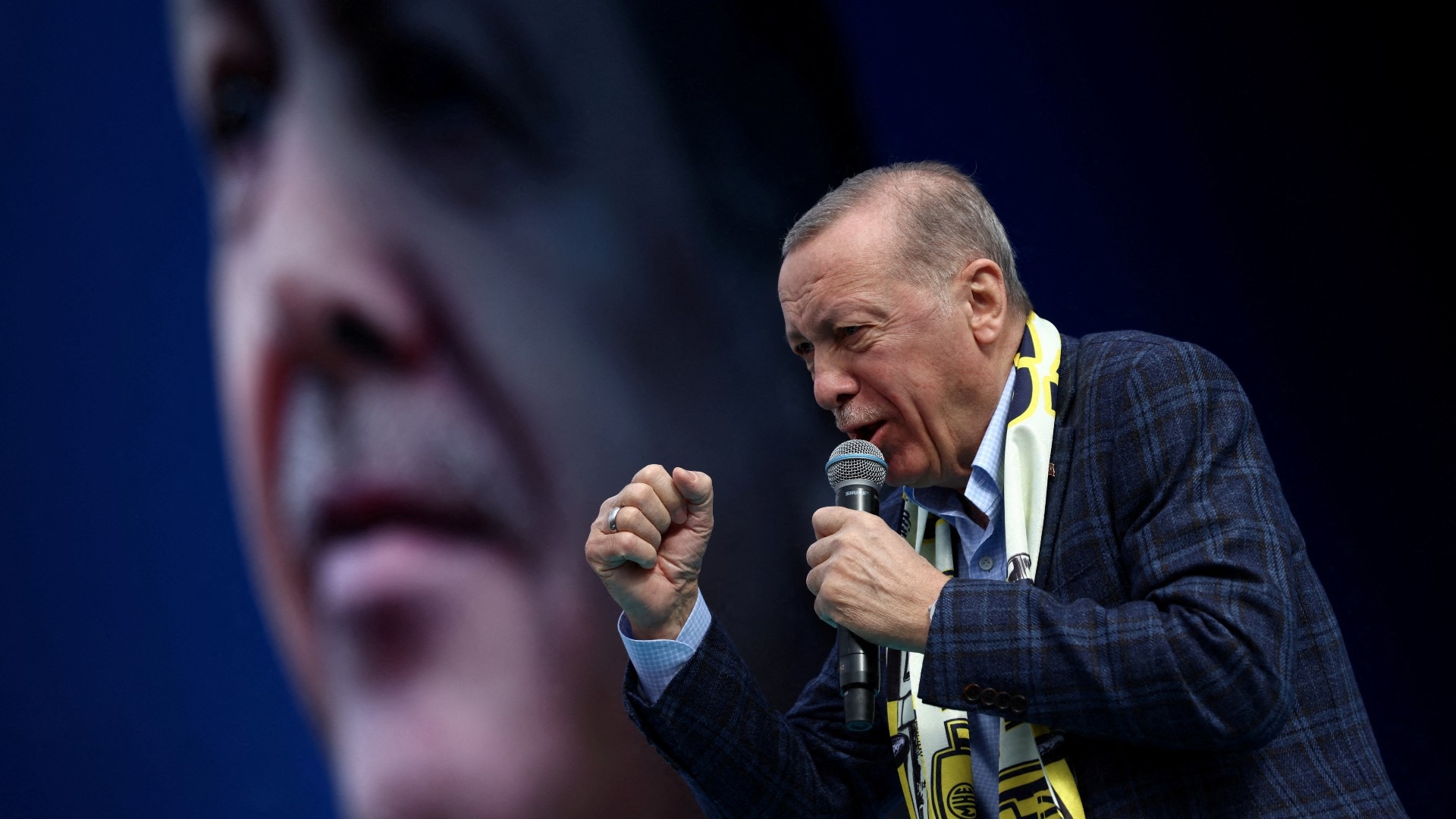

Turkey elections: Inside the campaign to give Erdogan one final victory

When the Turkish president’s people looked at the polling in June last year and saw that their ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) had dropped below the 30 percent mark, they became worried.

Annual inflation was surging, the Turkish lira was depreciating and people were unhappy. Many interviewed by Middle East Eye back then didn’t know how Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan could make a comeback in time for Sunday's presidential and parliamentary elections.

But Erdogan and his lieutenants developed a plan: they boosted wages for the public and private sector, flooded the market with cheap credit for home buyers, launched an amnesty on unpaid taxes, and began a major public sector recruitment drive.

And to stabilise the lira, they funded the central bank’s backdoor methods by taking money from Russia, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the UAE and Azerbaijan.

Populism worked. The AKP’s ratings rose month by month, jumping by six points between June and January.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Counterfactually, the twin earthquakes that devastated the south of the country in February did not undermine Erdogan’s popularity, nor did it halt the AKP’s recovery, a senior party official said. But it did change the campaign.

Erdogan the president became Erdogan the builder, or rather Erdogan the rebuilder. It was an image that played into the theme of national unity.

The president stopped his usual attacks on the opposition and started to underline his vision for a glorious and impactful future dubbed “the Turkish Century”.

He also began to unveil Turkish defence industry projects, one after another showcasing the national initiatives he was most proud of to the public.

"We wanted to show everyone the things we have already delivered while the opposition was busy with fights to pick a joint candidate,” the senior official said.

Ramping up the tension

AKP officials initially envisioned a calm campaign period, thinking that raising tensions wouldn’t help the president.

But as the holy month of Ramadan concluded, they decided to change their strategy: start tying the Table of Six opposition alliance to the pro-Kurdish People's Democracy Party (HDP), the bete noir of Turkish nationalists and the AKP base.

AKP campaign leaders were conscious of how tight the race had become. Even small things mattered and had the potential to be decisive. “This isn’t an easy election,” the senior official said. “The margins are very small.”

Erdogan was struggling to break through beyond 45 percent of the vote, and this more than anything else led to the campaign becoming polarised.

“Research indicated that the opposition’s indirect alliance with the People's Democracy Party is a distinct advantage for us,” a second AKP official said.

Joint opposition candidate Kemal Kilicdaroglu is neck and neck with Erdogan in the polls, posing the most significant challenge in years by combining his centre-left Republican People’s Party (CHP) with five right-wing parties.

But Kilicdaroglu doesn’t stand much of a chance if he doesn’t get support from the HDP and the Kurds in general. The left-wing alliance that includes the HDP is not in the Table of Six but is backing Kiligdaroglu.

The HDP’s ideological ties to the PKK, a Kurdish armed group designated as a terrorist organisation by Turkey, the EU and US, is the Achilles heel of this strategy. Turkish voters are 60 to 65 percent right wing and often identify as Turkish nationalists.

In recent weeks, the AKP’s new strategy has been clear for all to see: Erdogan has frequently attacked Kilicdaroglu, accusing him of collaborating with terrorists and “Qandil”, a nickname for the PKK, whose headquarters is in Iraq's Qandil mountains.

“Kilicdaroglu is an ‘other’ for many segments of society,” said one Ankara-based pollster, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

The pollster cited “his Alevi identity, the fact that he is leading the CHP, whose secularist and Turkish nationalist policies bring back bad memories to religious conservatives and Kurds, his bureaucratic past” as reasons Kilicdaroglu does not appeal to swathes of the public.

Though tensions over these issues have risen recently, they’ve always been in the background. A pollster with knowledge of the president’s inner circle said Erdogan favoured a polarising campaign from the start, but his closest advisors pushed back.

'He doesn’t think Generation Z exists'

Killicdaroglu, meanwhile, is able to harp on about the cost of living crisis with no danger of negative consequences for his own campaign. As Erdogan was launching a mini-aircraft carrier, his challenger was weighing the price of onions in a striking juxtaposition.

AKP officials have intentionally avoided the cost of living crisis in their campaign, an issue where the president is seen as weaker.

Erdogan’s economic dogma on low interest rates, and the resulting high inflation, is something still felt by regular people every day.

Instead, Erdogan talks about “family values”, accusing the opposition of undermining them by lending support to LGBTQ movements. “They are all gay,” Erdogan said in a rally last week. Since then, he has repeated this line anywhere he goes.

Privately, some advisors shake their head in despair.

“Erdogan has dogmas,” a person close to the AKP said. “Everyone is trying to connect the right side of his brain to the left side of his brain. He is conventional.”

Electorally this could be a handicap. Erdogan was raised politically in an age when university graduates were a small minority of the electorate. Today they are not. Erdogan is out of touch with them. Consequently, he does not believe in generational changes or nuances.

“He doesn’t think Generation Z exists,” the senior official said. “He thinks there are only voters.”

Nearly five million first-time voters, all Gen Z, will participate in the elections. And polls indicate Erdogan is suffering big time among them.

“Gen Z doesn’t care about conservative issues,” the senior official said. “Many of our colleagues’ children wouldn’t vote for Erdogan. We understand the nature of things, the zeitgeist, but it isn’t easy to transfer this knowledge to the president.”

The polls tighten

That said, Erdogan’s polarising rhetoric and campaign giveaways nonetheless began to sway voters, putting him above 45 percent in AKP polls.

Officials said several polls conducted by the party in May indicate that Erdogan is still leading in the first round and would win with a very narrow margin in a runoff, which would be held two weeks after Sunday’s election if no candidate gets more than half the votes.

That assessment contradicts polls released on Thursday, which give the edge to Kilicdaroglu, who is on around 49 percent.

'Erdogan has dogmas. Everyone is trying to connect the right side of his brain to the left side of his brain. He is conventional'

- Source close to the AKP

On Thursday, breakaway opposition candidate Muharrem Ince, who was polling around 2 percent, dropped out of the race, blaming the other parts of the opposition for waging a smear campaign against him.

Some have predicted that some of Ince’s vote will migrate to Kilicdaroglu and get him over the 50 percent line in the first round. Others, like the senior AKP official, say it will benefit Erdogan instead.

But if the presidential election does go to a runoff, AKP officials say they will rely on emotion, presenting Erdogan’s latest term to the public as momentous, trying to convince the public he deserves one final victory.

“The number of good guys around Erdogan is increasing,” the senior official said. “Rational people with plausible ideas are more active.”

In any case, all AKP officials acknowledge that Turkey has no history of presidential runoffs, and that the results in the parliamentary elections also held on Sunday will play an important role in the event of a second round.

“If we can retain the majority in the parliament, it will be a psychological boost to us,” the senior official added. “Turkish people don’t like cohabitation.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.