In pictures: Depictions of the Kaaba and Mecca's Grand Mosque throughout history

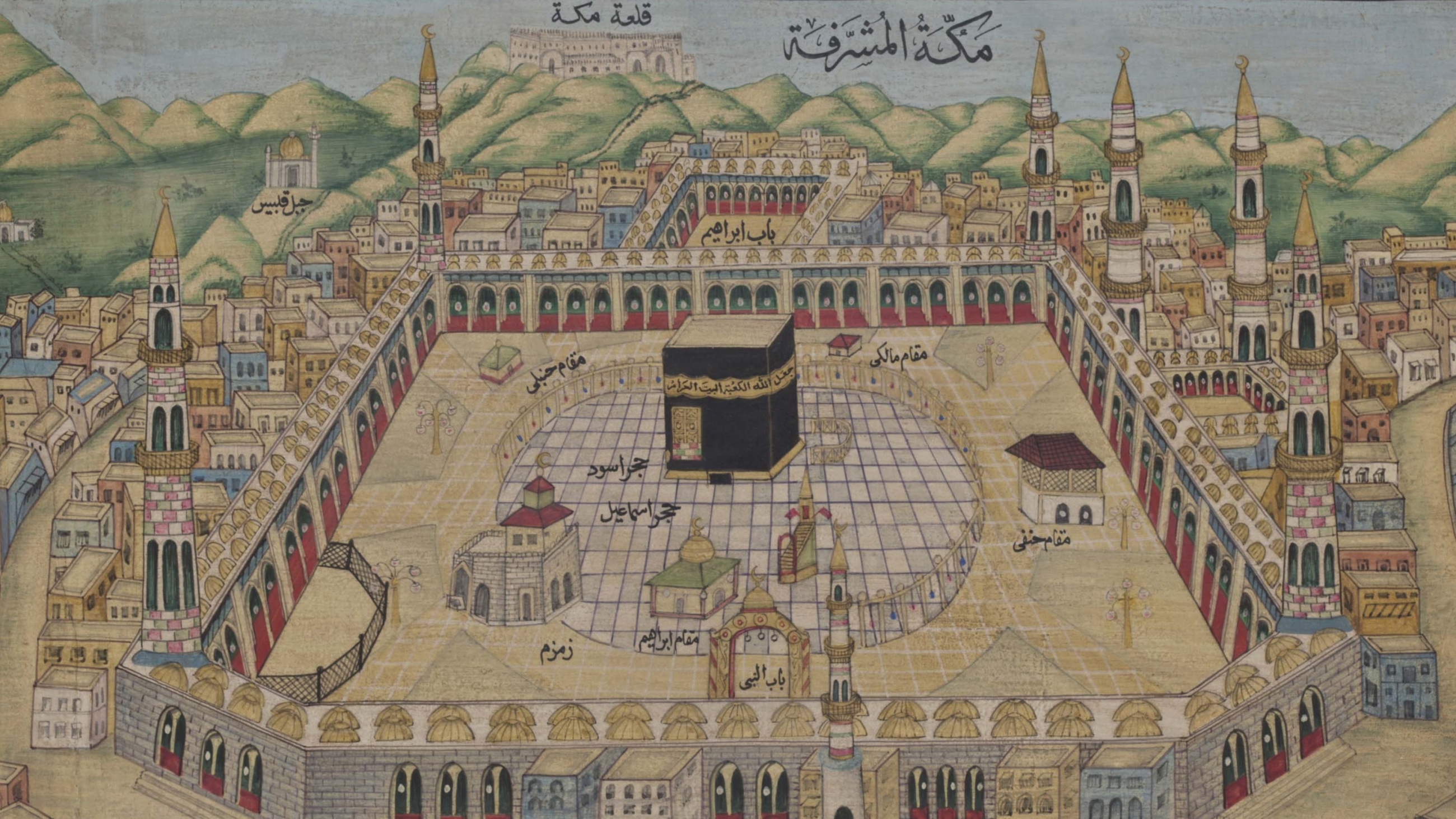

Located in the Hejaz region of what is today Saudi Arabia, Mecca's importance as a religious and cultural centre for the people of Arabia precedes Islam. Before the birth of the Prophet Muhammad in the sixth century CE, Mecca and the ancient cube structure, known as the Kaaba, were a site of pilgrimage for Bedouin tribes. Before Islam, the Kaaba housed idols representing a number of deities tht were part of a polytheistic pagan tradition. The Prophet Muhammad believed these were in violation of the original monotheistic faith that was established by the Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham), who in Islamic tradition rebuilt the Kaaba after its original construction by the first man, Adam. According to Samir Mahmoud, from Cambridge Muslim College, after Adam was expelled from heaven, what he missed most was witnessing the angels circumambulate "Bait al Mamur", an exact replica of the Kaaba that is believed to exist in heaven. God then asked Adam to build the Kaaba at the exact point on the earth that lies underneath the heavenly version. The image above was produced in 1575 and is featured in the 2005 collection titled Atlas of Maps of Mecca, and the top image is a late 19th-century painting by an unknown artist. (Above images: Public domain, top image: The Khalili Collections)

The Quran, which Muslims believe is the word of God as revealed to the Prophet Muhammad by the angel Gabriel, mentions the Kaaba in a number of verses, in which it is described as the first house of worship and a place of sancturary for the faithful. In Arabic, the name given to the Grand Mosque of Mecca is Masjid al-Haram, which means "The Sacred Mosque". A common misconception is that Muslims worship the Kaaba by directing their prayers towards it but such a belief would contravene Islam's strict monotheism, in which God has no material manifestation. The Kaaba is instead a symbolic marker towards which Muslims pray to God. Featured above is an 18th-century depiction of the Grand Mosque by an unknown artist. The city of Mecca would have been under Ottoman rule when it was produced. (Uppsala University Collection)

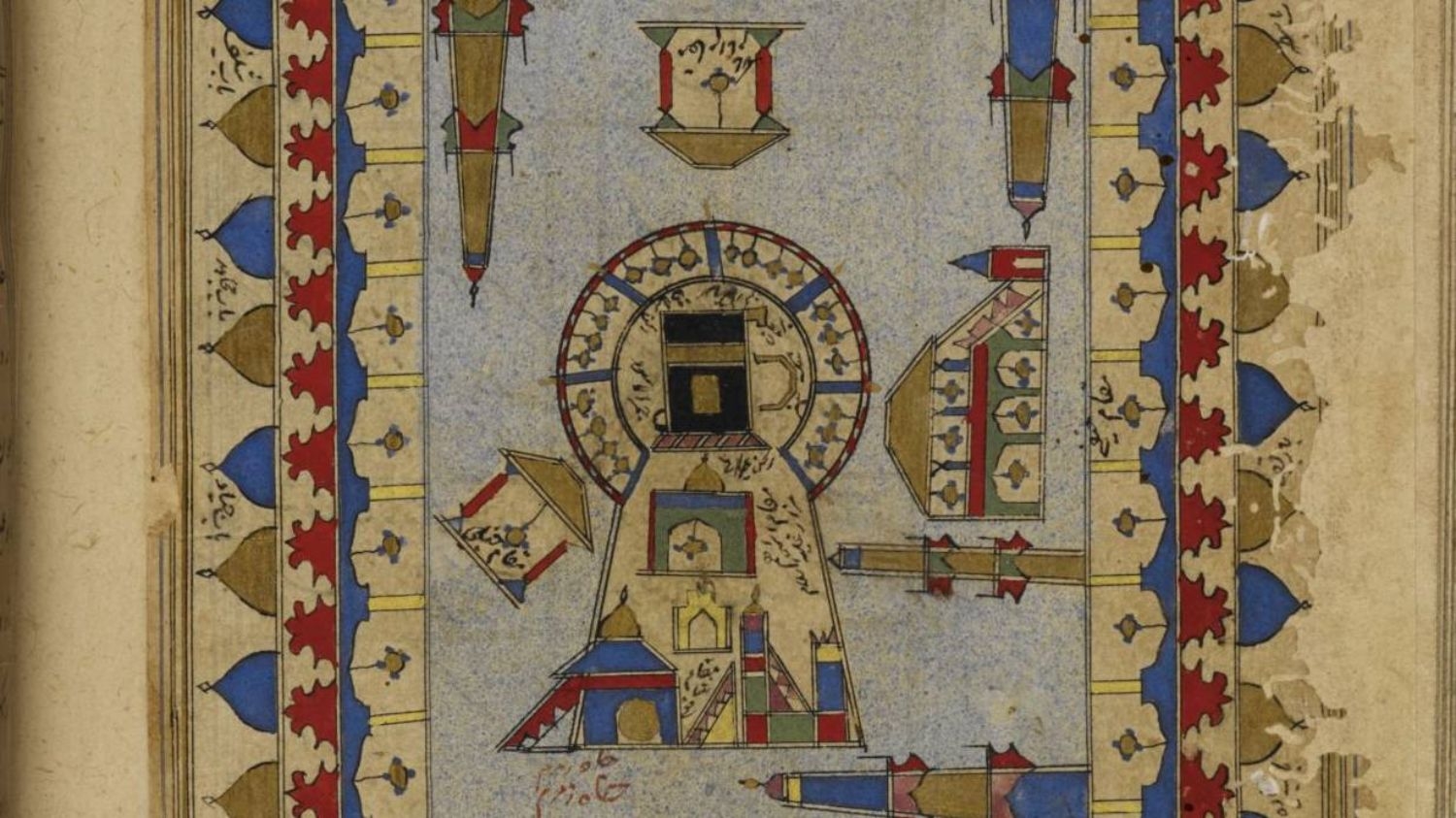

Around 20 metres east of the Kaaba is the Zamzam well, which plays an important part in Islamic tradition and pilgrimage rituals. According to Islamic tradition, the Prophet Ibrahim, his infant son Ismail, and his wife Hajar found themselves alone in the desert valley of Mecca, suffering from exhaustion. In desperation, Hajar is said to have walked between the hills of Safa and Marwa seven times trying to find something to drink. On God's orders, the angel Gabriel opened up the ground to reveal a spring, which became the Zamzam well. During the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages, the faithful reenact Hajar's search for water by pacing between the two hills seven times. The waters of the Zamzam well are considered sacred by Muslims and often taken back to their home countries after their pilgrimages have ended. The miniature above is by the 16th-century Persian-Indian writer Muhyi al-Din Lari and is found in his Persian language book Futuuhh al-Haramayn (The Revelation of the Two Sanctuaries), which is on display at the British Library.

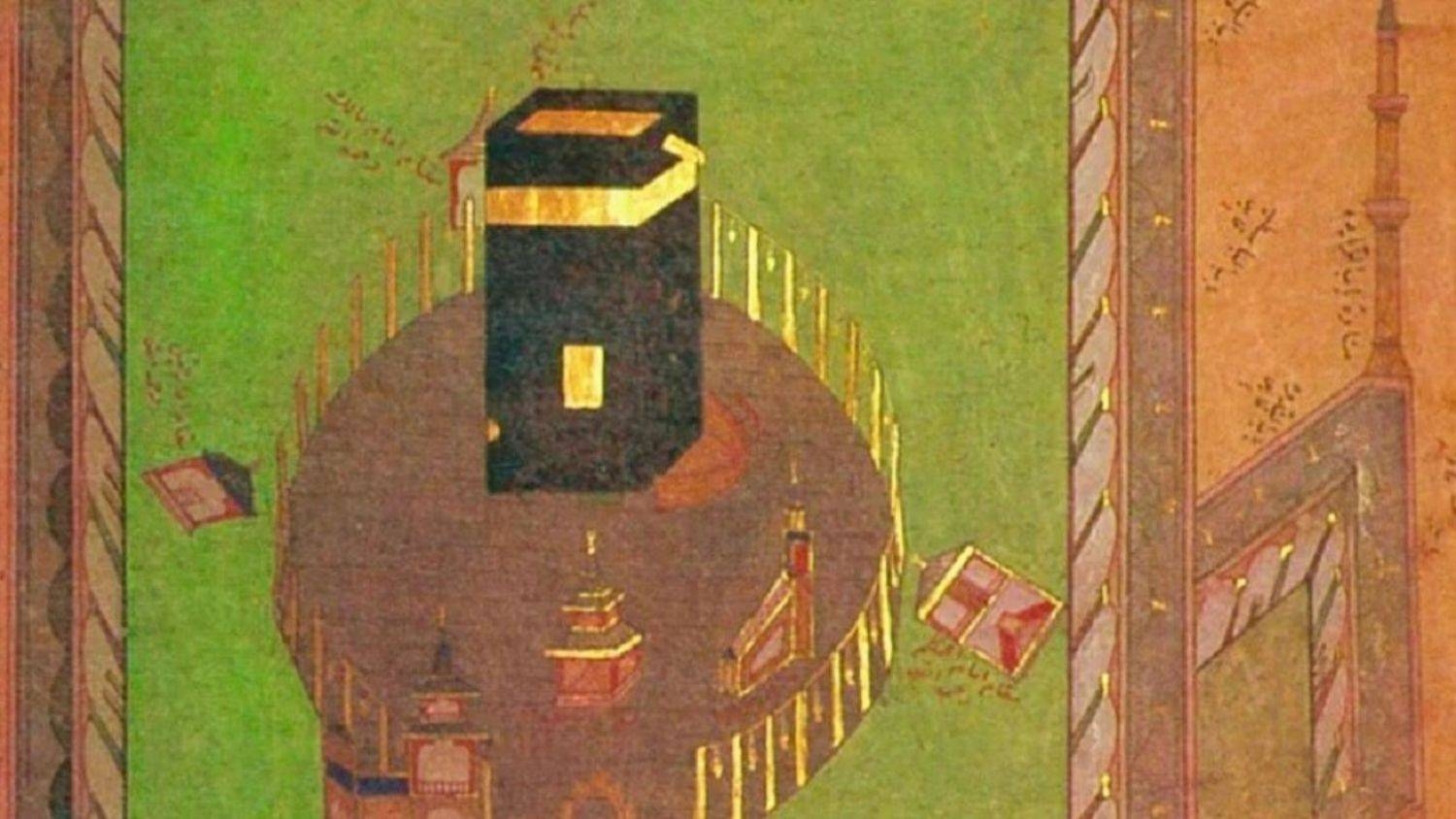

Before Islam, the Kaaba was considered a sanctuary by the warring tribes of the region - a place for peace where tribal disagreements would be set aside. One famous narrative in Islamic tradition involves the Prophet Muhammad and the tribes of Mecca before he received his revelations at the age of 40. To resolve a dispute between the tribal leaders over who should place the Kaaba's "black stone" in its rightful place after repairs to the structure, the prophet advised them to place the stone on a cloth and that the tribal chiefs should carry it together, thereby sharing the honour. The black stone, known as hajr al-aswad in Arabic, is believed by Muslims to have been sent down to the Prophet Ibrahim and holds tremendous ritual significance, as pilgrims will often try to kiss the stone during their circumambulations of the Kaaba. The image above is a 16th-century Ottoman depiction of the Kaaba, which features the black stone in its left corner. (Public domain)

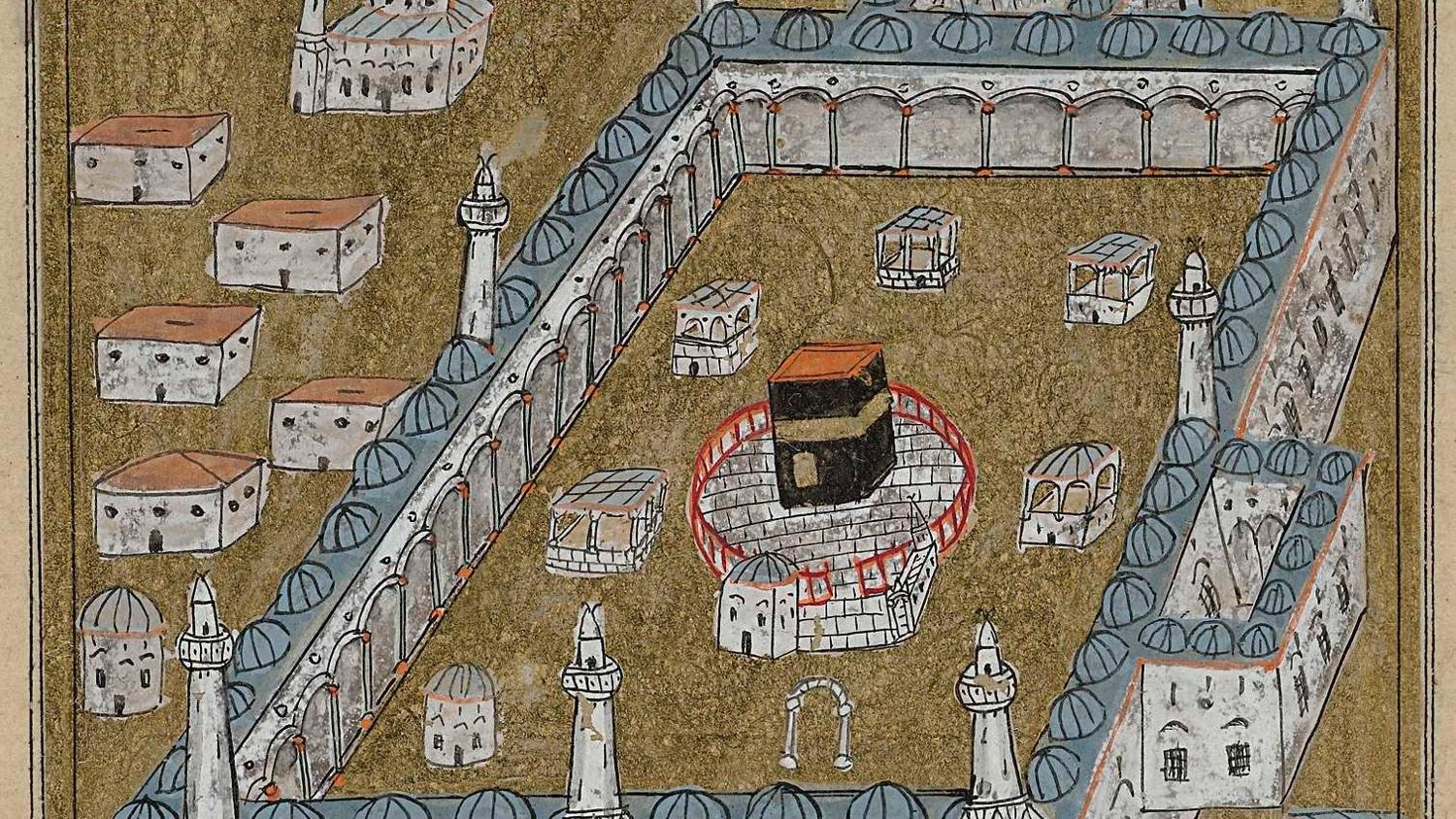

The Kaaba and the Grand Mosque have been refurbished and repaired many times, sometimes in response to natural disasters and at other times to accommodate increasing numbers of visitors. The Abbasid rulers in the 700s expanded the Kaaba’s courtyard, and after the Ottomans defeated the Mamluks and took over the site in 1517, they added their own additions to the holy sanctuary. In 1571, Selim II commissioned Mimar Sinan to add features, introducing traditional Ottoman-style small domes to adorn the flat roof of the mosque courtyard. The image above is a Persian miniature dated to the 1800s when the Ottomans still ruled the city of Mecca. (Rijksmuseum Amsterdam)

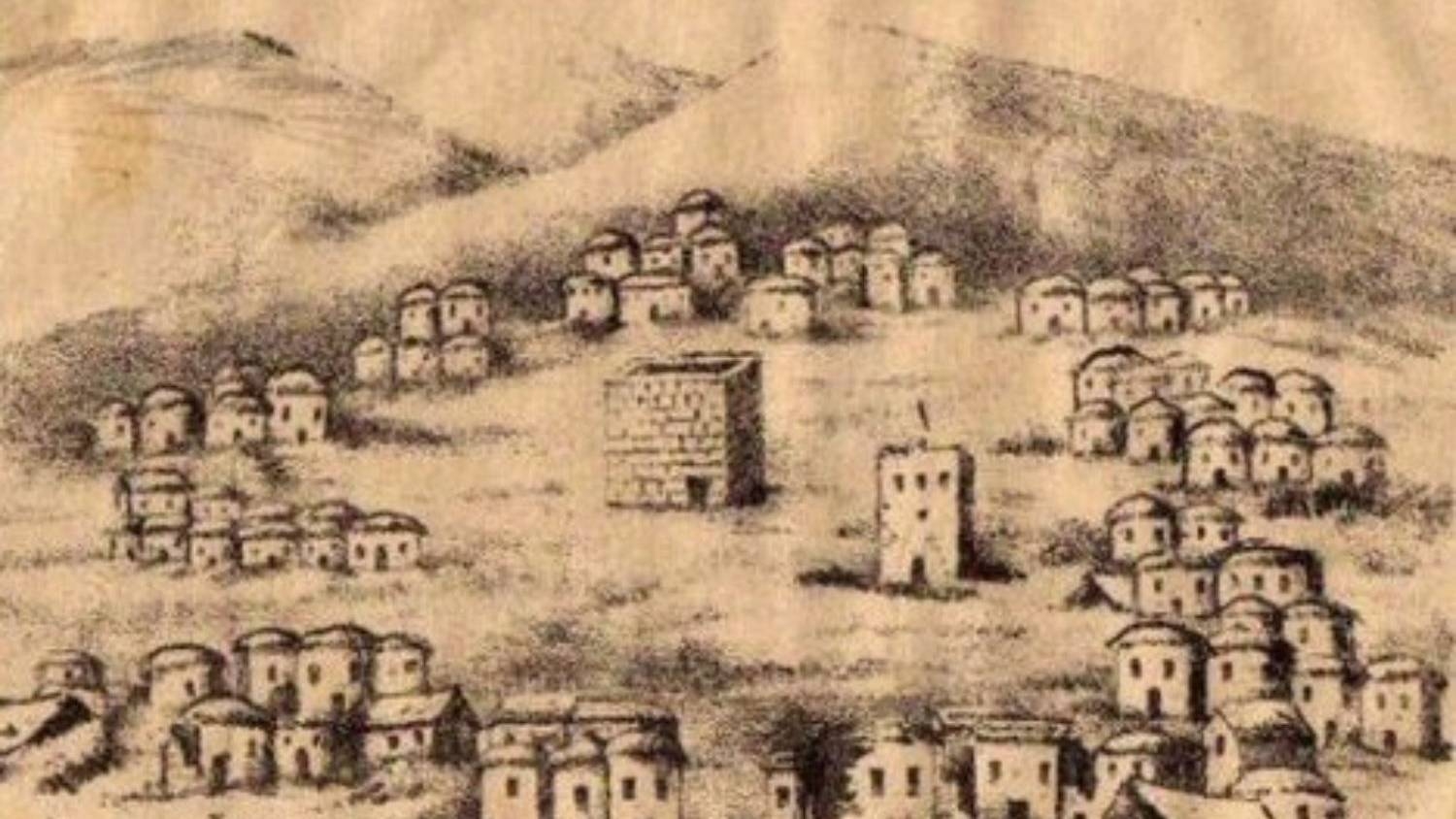

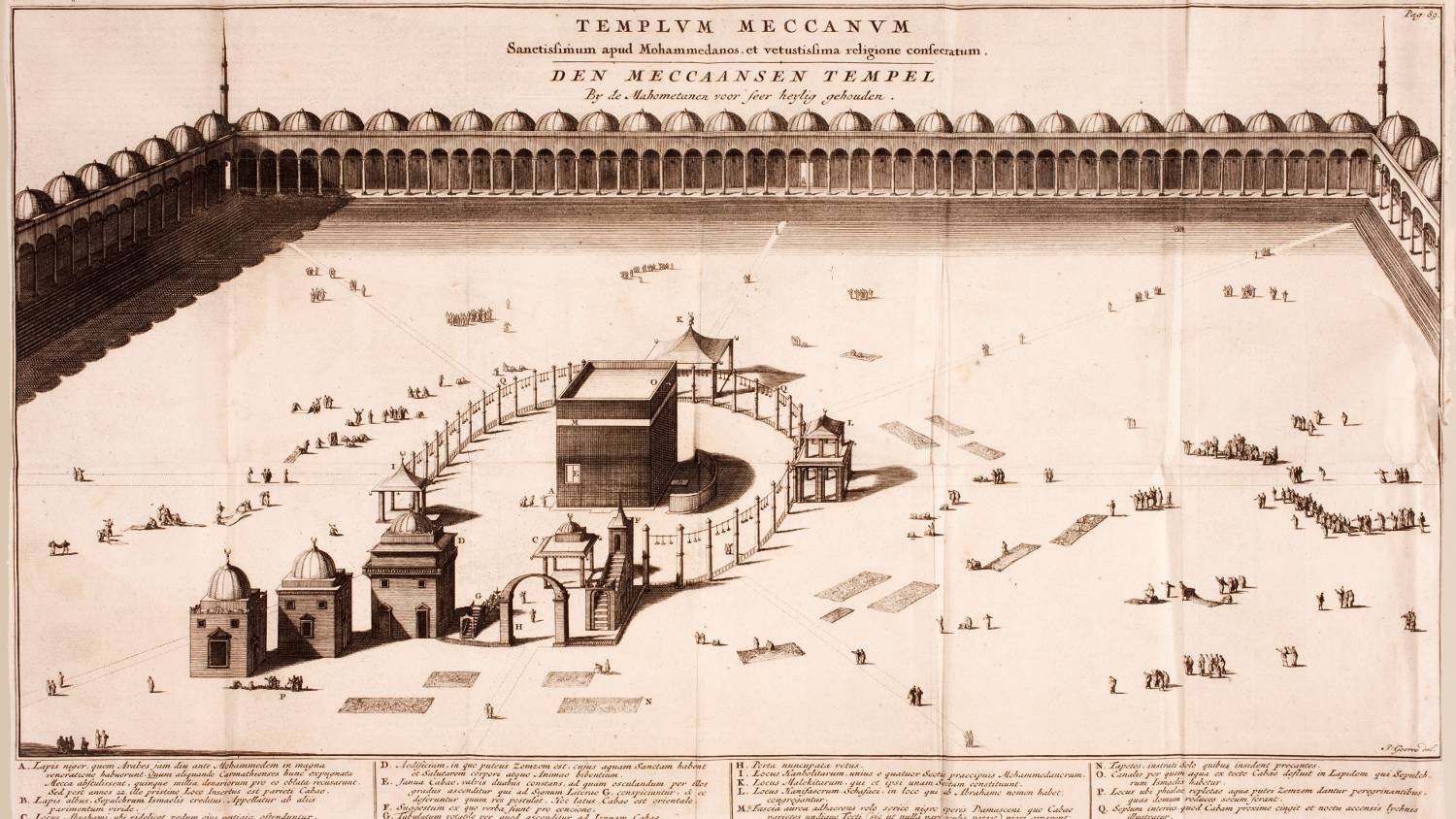

With the advent of photography in the 19th century, images of the Kaaba and Grand Mosque became widespread. But for centuries before, depictions of the holy place were uncommon in Europe. From around the 15th century onwards, with the start of the European age of exploration, travellers from the continent began visiting the Arabian peninsula for trade. Although they were formally prohibited from entering Mecca, which was only open to Muslims, there are a number of reports of Europeans smuggling themselves into the city disguised as Muslims or accompanying their Muslim employers. The image above appears in an illustrated version of the 1705 book De Religione Mohammedica (The Muhammadan Religion) by the Dutch scholar Adriaan Reland. In an era when most studies of Islam were polemical and aimed at vilifying its doctrines, Reland's work is notable in that it attempts to present an objective overview of Islamic beliefs. The scene was later copied and used in other European publications on Islam. (Peace Palace Library, Netherlands)

This photograph meant the world was no longer limited to artistic impressions and writings of Mecca. In 1861, an Egyptian army engineer named Muhammad Sadiq Bey travelled to the holy city as treasurer of a caravan of pilgrims. He took a camera and tools for the wet-plate collodion process - an early photo development technique in which images were developed using glass-plate negatives. Sadiq Bey's consequent pictures of Mecca won a gold medal at the Venice Geographical Exhibition in 1881. The picture above is the first photographic image of Mecca and the Kaaba, showing the now-familiar scene of the cube structure shrouded in the black cloth known as the kiswa. (The Khalili Collections/Muhammad Sadiq Bey)

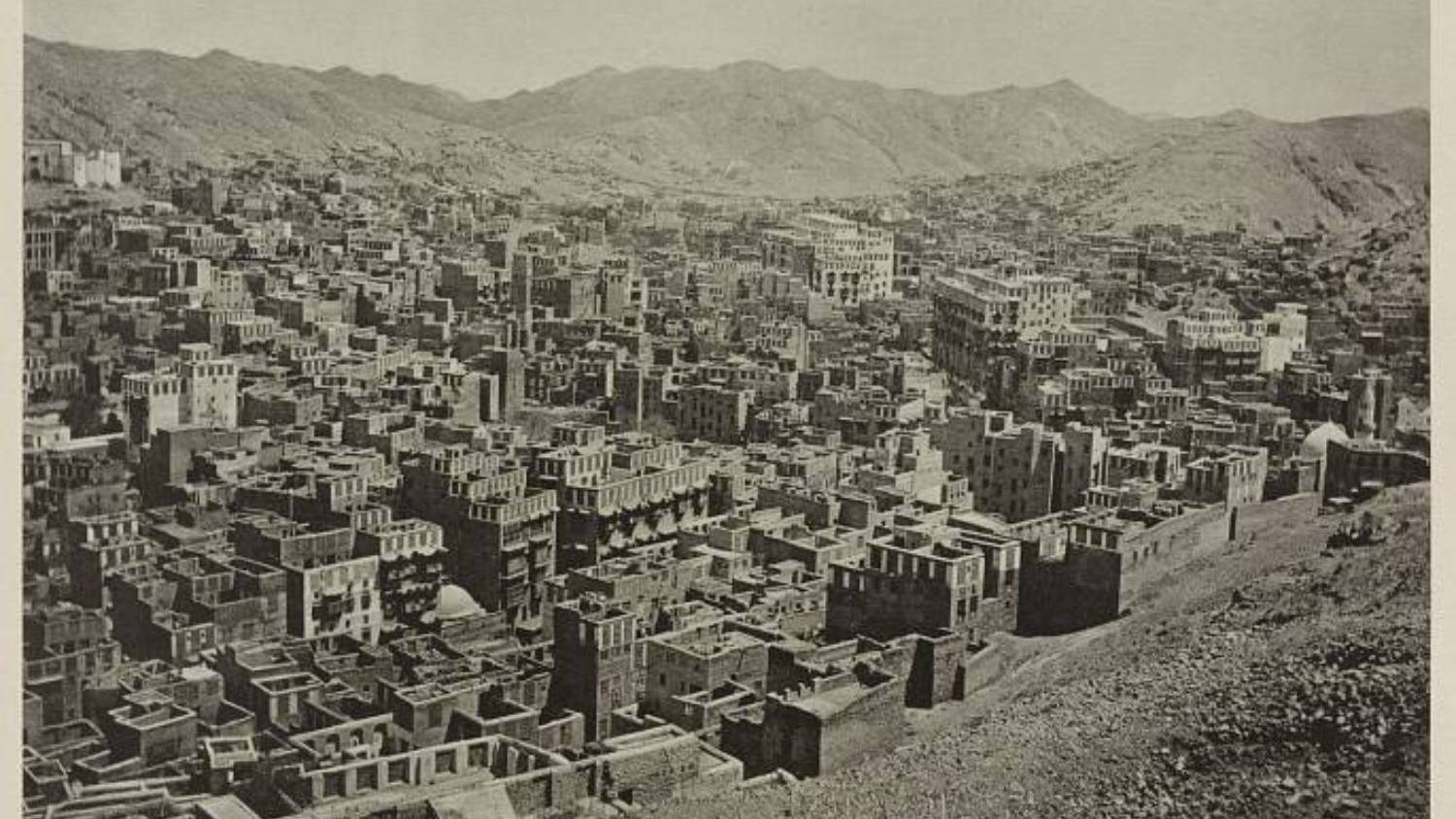

With time, photography became more accessible to others and one of Mecca's first native photographers was a man named Al-Sayyid Abd al-Ghaffar, who took more than 250 pictures of the city between 1886 and 1889. He worked alongside the Dutch photographer Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje who feigned conversion to Islam in order to enter the Muslim holy city. As their relationship developed, Hurgronje became more controlling of what his Meccan colleague could picture and even took credit for his work. The picture above was taken of the city of Mecca was taken in 1887 by Abd al-Ghaffar. (Library of Congress)

After completing the Hajj and before leaving Mecca, pilgrims perform a farewell circumbulation or tawaf, by walking around the Kaaba seven times. Abd al-Ghaffar captures the tawaf in this picture taken in 1909. (Library of Congress)

Mecca remained part of the Ottoman Empire until 1916, when Hejaz, the large western coastal region of the Arabian Peninsula, declared independence led by Hussein ibn Ali, the Sharif of Mecca. However, the Sharif's rule was short-lived and the area was soon conquered by Abdulaziz al-Saud, who occupied Mecca in 1924, eventually uniting Hejaz with other regions of the peninsula under his control to form the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In 1938, oil deposits were found in Saudi Arabia, and from that point the resource became the country's primary source of income. This meant the monarchy no longer needed to rely on the income brought in by religious pilgrims. In time, oil revenues would be invested into the holy sites in a seemingly never ending series of expansion projects. The image above depicts the Grand Mosque in 1937. (Public domain)

In 1955, during the reign of King Saud, the Saudis began an expansion project at the Grand Mosque. When the work was completed in 1973, the mosque was able to accommodate as many as 500,000 worshippers. The developments coincided with the boom in air travel in the 1970s, which made it easier than ever for pilgrims to reach the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. It also created an increase in demand for pilgrimages and almost as soon as the initial work was completed the need for further expansion became apparent. The next major expansion of the Grand Mosque started in the 1990s in a project overseen by the Egyptian architect Muhammed Kamal Ismail. He introduced the now-familiar marble paving, which was sourced from mountains in Greece. The stone ensured the ground pilgrims walked on remained cool, even in scorching weather conditions. Above is an image of the Grand Mosque in 2000. (AFP/Marwan Naamani)

Recent additions to the Grand Mosque area include the imposing 2099 foot Abraj al-Bayt (Towers of the House) complex, which houses a hotel and shopping centre. The development was built at the same time as the further expansion of the mosque itself, which can now accommodate around 2.5 million people. Critics say the new structures around the Grand Mosque are an eyesore and distract from the Kaaba and its surrounding holy sites. (AFP)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.