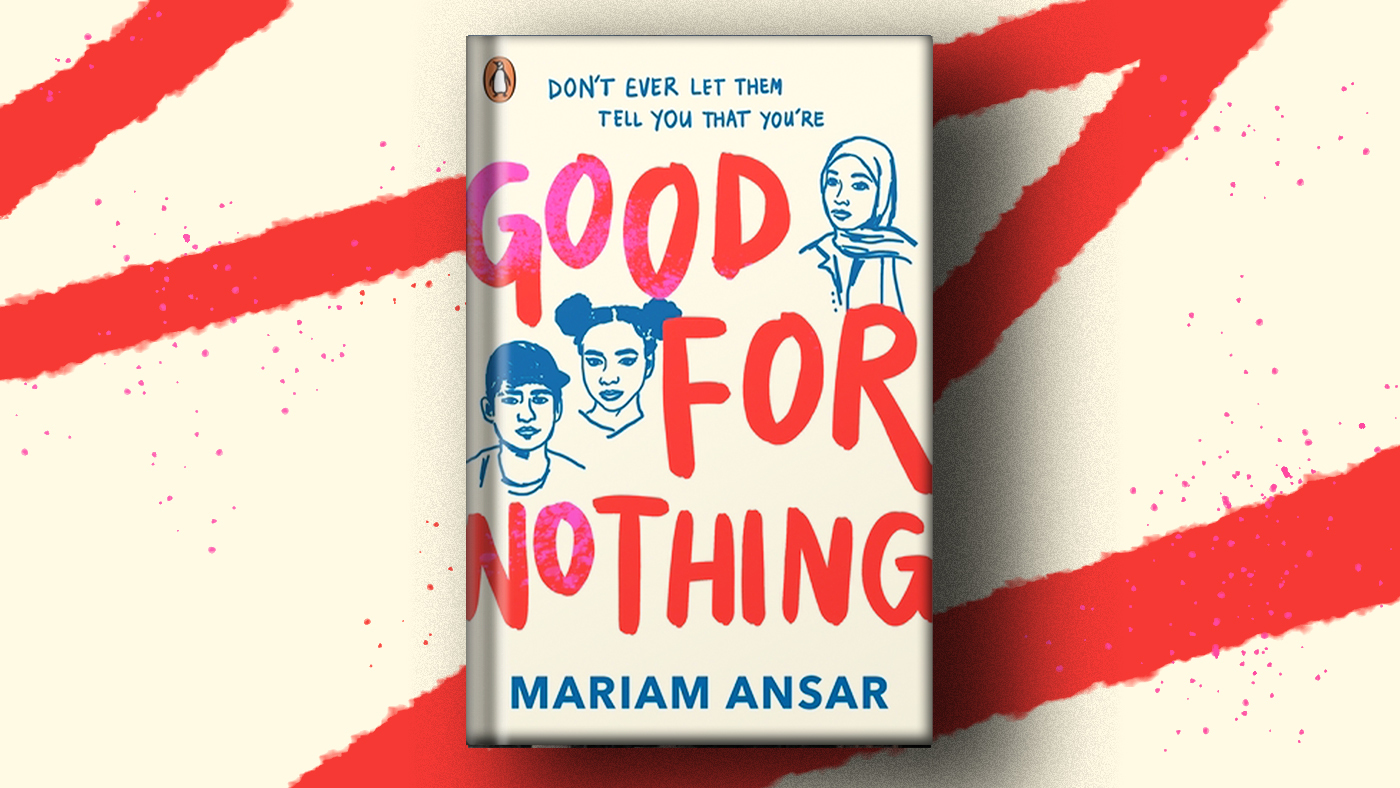

Good for Nothing: British Muslim author Mariam Ansar on skewing stereotypes

There is an essay by Zadie Smith called "Speaking In Tongues" which I still refer to constantly. Even six years after graduating from university, where I sat in the book-strewn refectory room of my old Cambridge college, and looked at it for the very first time.

The exercise I was involved in - a weekly seminar named Practical Criticism - revolved around analysing a text without considering its contexts: who wrote it, when did they write it, what socioeconomic factors could they have been responding to?

Such emotional aspects had to be divorced from the reading. We were taught to consider words, rhyme schemes, pentameters and tetrameters instead. Ironically - despite my old supervisor’s efforts - context has always been the first thing I consider in any text.

Reading "Speaking In Tongues" was no different.

In it, Smith - who also attended the university, but was born in north London - discusses the particular experience of gaining a “double voice” in a prestigious environment. A sort of blending, a code-switching, or costuming of vowels and consonants so that you are considered passable; acceptable, if only by your more privileged peers.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

I can understand that. I’m from Bradford: a town in West Yorkshire best known for its large South Asian population, the birthplace of the singer Zayn Malik, many well-respected restaurants, and a certain brand of deprivation-induced delinquency.

When I was at Cambridge, I attended lectures and ran into supervisors who told me that the reason why the accent I had at the time didn’t pronounce its "Ts" was less to do with it being northern and more to do with it being working class.

I watched friends smile, unconvinced, when I suggested that the north deserved more attention for all its flaws and lack of government funding.

I went to mingling events with other British-born Muslims - naively expecting some camaraderie - and found that saying you’re from Bradford got its own set of laughs. Some non-funny jokes. Everyone in your ears: kasmey (I swear), yara (man!), bro.

My tongue gained another in all of those scenarios. Or, at least, my mouth was so heavy with unspoken words that it felt like I needed another one. If only to be taken seriously. If only to be heard beyond half-baked stereotypes; privileged braying laughter; the regional distinctions between people of colour.

But the way I spoke back in primary school - when we lived at my grandma’s house, and all my friends called brown-brick terraced houses "home", and I walked along back streets surrounded by kids playing cricket with makeshift stumps - remained inside me. Maybe confident, maybe defiant. Or both. It refused to be erased.

Retiring Muslim tropes

Retrospectively, I’d like to believe that I chose to remember that first tongue. That some part of me always recognised its lack of futility. The absence of good-for-nothing status.

So it was during a free hour in my college room, when I felt particularly isolated from the ivory tower I believed I’d chanced myself into, that a character called Eman, and another called Amir, and another who would later be named Kemi, strolled into my head.

There are a few genres which always come up when you’re searching for a Muslim-centric narrative. Certain tropes that are somehow palatable to the publishing industry:

Hijabis that fall for white non-Muslims and lose their hijabs in the process. Terror tales that warn of the dangers of religious extremism in sensationalised depictions of Afghanistan or Iraq. Long sweeping fantasies in vaguely Middle Eastern countries. Trauma-driven narratives that highlight all the negatives of practising your faith, and recently, trauma-driven narratives that highlight the absence of practising your faith at all.

It isn’t up to me to specify which is okay and which isn’t: stories have and will be told by those that are lucky enough to be given the permission to do so, whether by themselves, or by someone else.

But I can say - when I began drafting my novel - that I was tired of the repetition: the ceaseless slog of the same, the same, the same in order for readers to ignore the difference, the difference, the difference of being Muslim. I remain tired of this.

I read The Iliad by Homer during the drafting years, seeking inspiration. I made space for the text on my bookshelf, and instantly found myself drawn to the two princely brothers of Troy: the young, reckless Paris and the responsible, generous Hector. Paris is responsible for the deaths of many.

But it is Hector who dies in an attempt to undo Paris’s mistakes. I thought: "Doesn’t everyone know brothers like that? The one that is a fuck-up and the one that knows he has to save the other? And carries this responsibility until the end?"

I kept notebooks dedicated to shaping my characterisation of Eman, Amir and Kemi. I created a brother for Amir: Zayd Ali. The Hector to his Paris, the one who would always save him, even if it meant his own death.

Though the narrative changed after these initial thoughts, Zayd’s death did end up becoming the catalyst for the entire novel.

I want the texts that are about Muslims to be just as rich and sharp, just as perceptive and loving, as the texts of the classical era; or the Victorian; or the medieval. I want them to be emotionally difficult and tangibly rewarding. Beyond interracial love stories, beyond headlines seeking to sensationalise the worst of us.

After all, the tradition of Muslim characters is nothing if not interesting: Shakespeare’s Othello is -in some interpretations - ambiguously racialised as deriving from Muslim Spain. Shelley’s Frankenstein features orientalised depictions of the Ottoman Empire in the passive, submissive Safie.

Contemporary texts can offer more scope, more depth, more richness: Fatima Farheen Mirza’s A Place For Us and Leila Aboulela’s Bird Summons instantly come to mind. The literary starting point is obvious. It’s a relay which - I feel - begs to be continued.

Today the silent majority of Muslims pray and buy treats for their family after dinner. They struggle with their hijab, and search TikTok for style tips. They play football and argue about their teams with stringent fervour.

They’re students, shopkeepers, taxi drivers, teachers, accountants, journalists, doctors, entrepreneurs… Who writes for them? The real people? Including the northern, brown-skinned, kasmey-yelling bros who act hard, and feel hard, but aren’t, underneath it all?

A picture of West Yorkshire

Good For Nothing fixates on a town named Friesly. This is my fictional homage to Bradford, Dewsbury, Doncaster, and the likes.

In Friesly, the streets are steep and winding. The hedges are overgrown and evergreen - a consequence of setting my tale in a rare English summer. A history of wool mills and the struggle to end Victorian child labour permeates the background. South Asian aunties go for walks in parks which feature polluted ponds and shuffling, shivering homeless people.

Family restaurants boom with shoddily planned weddings and an extensive mithai collections. The barbers are perpetually busy, the Asian supermarket is manned by the wise and the vicious. Young people are dealt their silent struggles and go about their business under the watchful eye of their parents and the police.

My characters - much to the dismay of the students I teach every day at a school in Bradford - are not based on anyone in particular. Yet they are an amalgamation of everyone I have met, seen, spoken to, and not spoken to. I think that it is the job of the writer to bottle magic.

The quiet wistfulness of girls who have always done their homework, the frenzied charm of troublemakers skipping out on detention, those that walk in the golden glow of talent, and those that simply don’t. I also think that it is the job of the writer to notice what goes unnoticed - and, to borrow a phrase from Toni Morrison: “to make the local global”.

I think that it is the job of the writer to bottle magic

I am unsure if the silent majority recognises what stories they live every day. Certainly the young child that I was on my grandma’s street, arm in arm with a neighbour with the same name, face, and stance as my own, wouldn’t.

Nor the mosque attendees of mine and my siblings’ youth, who drew unflattering images of our teachers and flashed them to the class with ease.

My sister’s retelling of three South Asian women, clad in salwar kameez, sharing a purse to buy themselves chocolates. My students, arguing with such colourful aggression, and wondering why I can’t tell when they’re joking. Then there are the stories from Pakistan, Latvia, Romania, Croatia and - oh, just down the road.

Still, there is a certain feeling I get, reading my own book with the form class I was given to take care of. Year 9 are livewires, emotionally hectic - in the throes of their own growing up. I see them most days, after two lessons and break time. All different heights and sizes, all relaxed and worn-in like their school uniforms.

They’re the type to laugh a lot, and they are kind with their questions, and they are so excited to speak that they interrupt one another easily.

There is a palpable glee when they read certain sentences in Good For Nothing aloud: "kasmey"; "he was pissing me off"; "the owner of Mahmood’s Foods"; "it’s because of the jalebi"; and most recently, the very simple statement: "shit, man".

That glee is evident in me, too. They speak with one tongue and recognise this tongue in others.

And no one has ever made them feel worse for it.

Mariam Ansar's debut novel 'Good For Nothing' is published by Penguin

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.