Hakan Fidan: How Turkey's foreign minister could shape the new world order

Russian President Vladimir Putin did not just invade Ukraine to grab a chunk of the Black Sea coastline back. He was more ambitious than that: he wanted to change the world order; to show the West it no longer called the shots.

But his multipolar world has had the worst possible debut. Ukraine has become a military disaster. Russia has lost at least double, or possibly even triple, the number of men in 17 months of fighting that the Soviet army lost in nearly a decade of war in Afghanistan.

Putin has also failed to keep his allies, China and Iran, with him. Whatever words Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping use to sugarcoat their relationship, the bald truth is that China is at least a decade away militarily from the role of global challenger to Washington. Putin’s invasion bounced China into a role that it is not yet ready to play.

China’s main strategic aim is to increase its trade with Germany, not to threaten it regularly with nuclear armageddon, as Putin’s inner circle does.

Russia’s other main ally in this venture is not happy either. Looking northwards is not as attractive to Tehran as it first seemed a year ago.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

At that time, a delegation of the bosses of the leading Iranian state automotive firms had returned from Moscow with large dollar signs shining in their eyes. Western sanctions had just hit the Russian car industry, and Russia wanted to tap Iran’s sanction-busting expertise. Russia was buying whatever Iran produced: engine blocks, axles, drones, you name it.

Contrast that with the mood in Tehran today. The current row is over Russia’s explosive decision to back the UAE’s claim to three islands that Tehran claims are Iranian near the Strait of Hormuz.

A senior commander in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), Mohsen Rezaei, said that Russia should “correct its position”. High-profile conservatives, such as Mohammad-Javad Larijani and Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, accuse Moscow of “playing the American game” in the Gulf.

Coping with chaos

There are other cracks in the Russian-Iran relationship, such as the recent “informal and unwritten” agreement between the US and Iran, by which, in exchange for some sanctions relief, Iran pledged to expand its cooperation with international nuclear inspectors, not sell ballistic missiles to Russia, and stop attacks on American contractors in Syria and Iraq. As a party to the 2015 nuclear deal, Russia views an interim agreement with suspicion.

Iran is finding out that navigating the new world order is more difficult than watching the old one crumble. But not all Middle Eastern powers are following Iran down this path. There is one country, Turkey, that is coping with the chaos swirling all around it, even though it, too, has regularly fallen out with Russia and Nato in the past.

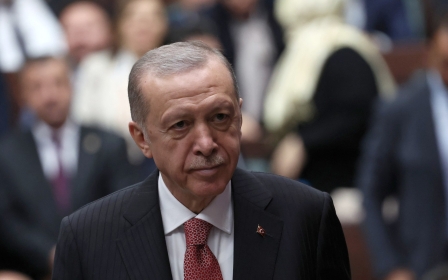

And there is one appointment that President Recep Tayyip Erdogan recently made which could prove crucial in this regard. While everyone homed in on the U-turn in his monetary policy with the appointment of a new team of economic and financial advisers headed by Mehmet Simsek, Erdogan made another appointment that was just as important to his third and last term of office.

Fidan has rebuilt MIT as its head for the last 13 years. He reestablished it as an organisation that evolves and adapts to new threats

It was the promotion of Hakan Fidan, the former director of MIT, Turkey’s National Intelligence Organisation, to foreign minister.

As a rule of thumb the world over, the job of running a national intelligence agency is reserved for hawks. Such posts are so sensitive to absolute rulers of the Middle East that they are given only to close family, an elder brother, or son.

Fidan breaks these rules. He is a political scientist who trained under the Scottish historian and academic Norman Stone. He is not a military hawk, although he served in the army.

He is an intellectual, not a thug. He reads books, which is more than can be said for a couple of recent US presidents. His English is as fluent as his intellectual curiosity is wide. He is as comfortable debating the poor prospects of Scottish independence as he is Islamic theology.

For these reasons, Fidan’s appointment as head of MIT in 2010 was greeted with much suspicion from the Turkish security establishment. He was not one of them. He was too young. He would not last. And the criticism came not only from them: Ehud Barak, then Israel’s defence minister, described Fidan as a “friend of Iran”, saying that secrets shared with Turkey “could become open to Iran over the next several months”.

Last bastion

Before Fidan took over, MIT was as inward-turning as all other Turkish institutions were. The joke went that MIT knew the names of the mistresses of every minister and MP, but not the name of the head of intelligence of the Syrian army.

Fidan had his baptism by fire. Before joining MIT, Fidan, who was then deputy undersecretary at the prime minister’s office, joined secret negotiations with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in Norway. The PKK taped the conversation, and the tape came to light when a PKK member was arrested by Belgian police. They passed it on to their counterparts in Turkey, who were controlled by Gulenists, who leaked it.

Gulenists had infiltrated large parts of the Turkish state: its police force, judiciary, and a large part of the media. They had their own universities and a network of private schools. MIT was the last bastion within the security establishment that the Gulenists had yet to capture.

Gulenists pushed Ramazan Akyurek, who had been appointed police intelligence chief several years earlier, for the post of MIT chief in 2010. Gulenist pundits and publications repeated Barak’s line that Fidan was “pro-Iran”.

Erdogan dug his heels in, although the split with the Gulenists had yet to take place. Akyurek was later accused of turning a blind eye to the assassination of Armenian Turkish journalist and intellectual Hrant Dink, and to illegally wiretapping intellectuals and politicians. He was sentenced to life imprisonment in the Dink case.

The Gulenists had one more go at trying to unseat Fidan. His office in the old MIT headquarters in Ankara was the first government office to be bombed by helicopter in the abortive military coup in 2016. For hours, everyone thought Fidan was dead.

Not for the first time, his peers underestimated the abilities of the quiet survivor. Fidan has always been intrigued by the relationship between intelligence and foreign policy, which was the subject of his Master’s thesis. Completed in 1999, it reads today somewhat ironically, because Fidan uses the CIA and MI6 as models around which Turkish intelligence should orient itself.

This was when American power was at its height. The winner of the Cold War was hailed as the undisputed leader, militarily and economically, of the world.

Building institutions

The two decades that were to follow produced the “war on terror”, in Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Syria and Libya, and now Ukraine. They are all major western intelligence and foreign policy failures. But in 1999, all that was to come. At the time, the US really did think it could break and remake countries at will.

But what attracted Fidan about the US and British intelligence services was how they were organised and embedded as institutions. This is a very Turkish concern, because the country has been plagued by an absence of institution-building. Fidan wanted to change that and went about remaking MIT into a professional, dependable institution that delivers.

He did the same with TIKA, the Turkish aid agency. Fidan used TIKA as an instrument to expand Turkish influence in the Balkans at a time when the cauldron of ethnic war was still hot to touch.

Fidan has rebuilt MIT as its head for the last 13 years. He reestablished it as an organisation that evolves and adapts to new threats. He created a division devoted to strategic analysis and one devoted to cyber warfare. It’s a non-political organisation. Unusually for Turkey, you rise through its ranks through merit.

A non-partisan intelligence service is particularly important. Had Joe Biden’s preferred candidate Kemal Kilicdaroglu won the presidential elections, MIT would have been given to the far-right leader Umit Ozdag, along with three other ministries. This was the substance of a secret protocol that the loser Kilicdaroglu has only just revealed now.

Fidan is not a politician, although his relationship with Erdogan is close. Erdogan has had his back on more than one occasion, and Fidan notably stayed loyal when others around him - such as former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu - broke ranks to join the opposition.

Fidan's hardest task lies ahead of him. The old world order is on the way out … But the new world order is a long way from forming

The key to Fidan is that he regards himself not just as the servant of the state, but as its guardian. Even before he moved to the foreign ministry, MIT had some important files from conflict zones. It was the agency that secured Azerbaijan’s victory in the latest bout of fighting with Armenia. It was the agency that oversaw the Turkish pushback against the Wagner Group and renegade general Khalifa Haftar in Libya. It negotiated the now-defunct grain deal between Ukraine and Russia, and countless prisoner exchanges.

During the course of his tenure, MIT created many enemies. Rival intelligence agencies don’t like competition, especially from an effective operator.

On Fidan’s appointment as foreign minister, opinion in Iran appeared divided. The Telegram channel Afsaran-ir, which is close to the IRGC, praised Fidan for his ties with them after Israeli forces raided the Gaza Freedom Flotilla in 2010.

The Iranian Diplomacy website went the other way, with Islam Zolqadrpour writing: “Between 2010 and 2020, under Fidan’s leadership, Turkey deployed security and intelligence strategies which were all against Iran’s interests in the region. Turkey’s National Intelligence Organisation is the main sponsor of terrorist and warmonger organisations in northern Syria, and Fidan is the main figure organising their policies.”

The line about acting against Iran’s interests is partially correct. But it depends on how you define interests.

Ringside expert

MIT has thwarted 10 different Iranian assassination squads from all three Iranian intelligence agencies, who were not only targeting Israelis and Jews on Turkish soil but also in one case, using Turkey as a springboard for an operation in the Caucasus. Only some of these operations have come to light.

Israel has also done a body swerve on Fidan. When he was appointed MIT director in 2010, Haaretz reported Israeli defence establishment concerns. Now, he is credited with rebuilding relations with the leadership of Israeli intelligence. What the Israeli media fail to point out is that Mossad operations in Turkey continue to be intercepted.

During his tenure, Fidan has become something of a ringside expert on the politics of the Gulf. This, too, was forced on him. He was the first to take Saudi calls begging him to bury the affair of the botched murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul.

He was the first to make sure the tapes of the murder went public, and the first to brief CIA Director Gina Haspel on their importance. Similarly, he was the first to restore Turkish relations with the man who ordered Khashoggi’s murder, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

Now, Mohammed bin Salman and Emirati leader Mohammed bin Zayed are at loggerheads, but both camps have warm and growing relations with Turkey. This would all make an interesting political science lecture after Fidan retires; the title of one session could be: “How to befriend the two men who did their best to have me killed.”

Fidan’s hardest task lies ahead of him. The old world order is on the way out, although Nato does not seem to know it. But the new world order is a long way from forming.

What you have instead is a diplomatic minefield as dense, and as boobytrapped, as the one facing Ukrainian troops trying to recapture lost territory.

Dividing the world into Manichean blocs - democracies and autocracies - falls as a conceptual model at the first hurdle. To protect their way of life, liberal democracies are shedding their liberalism, particularly towards ethnic minorities, and becoming more nakedly mercantilist abroad. The most egregious abusers of human rights are rewarded with bailouts and arms sales.

This situation requires nuance, intelligence, and the ability to listen and assess information. It requires someone who has spent time establishing personal relationships and now has the means to enact foreign policy.

It requires an intellect capable of giving voice and shape to foreign policy. That, the new Turkish foreign minister has in abundance. Other foreign secretaries would do well to take him and Turkey seriously.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.