Turkey: Visually impaired Algerian woman deported to Syria after police check

An Algerian woman residing in Turkey was deported to northwestern Syria after what she thought was a routine police identity check.

Djazira Bali, who is visually impaired, lived in Istanbul with her Syrian husband Muhammed Zekeriya, and their children, but had travelled to the southern city of Reyhanli to obtain financial support from a friend for a medical procedure.

They were stopped by a Turkish police patrol and asked for their identity papers but were only able to produce photographs of the documents.

The officers refused to allow the pair to retrieve their documents from where they were staying and instead, the couple says they were deported within 24 hours to the Syrian city of Afrin, which is under the control of Turkish-backed Syrian rebels.

Bali and Zekeriya’s case is part of a wider Turkish crackdown on migrants and refugees.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

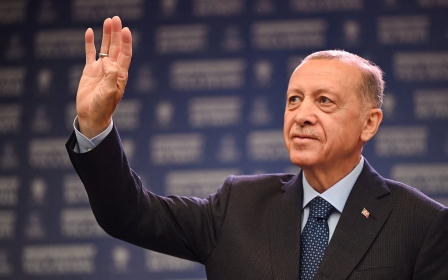

In recent months, following the re-election of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in May’s presidential election, authorities have stepped up their campaign to deport Syrians and others deemed to be living in Turkey illegally.

Immigration was a key issue during the election and both Erdogan’s ruling AKP and the opposition CHP courted anti-immigrant sentiment in order to gain support from voters.

“The police could have easily checked our data on their tablets, but they didn’t,” Zekeriya said, referring to a central database that patrols can access to verify a person’s identity.

As a result, what should have been a straightforward stop turned into a nightmare for the family who were uprooted from their lives in Turkey, despite being eventually allowed to return home.

We slept in a street

In an instant messaging conversation with Middle East Eye, Zekeriya recounted his family’s story.

He said the couple had been married for six years but had run into financial difficulties after the birth of their children.

Their money troubles have been further exacerbated by Bali’s visual impairment, which requires specialised lenses at a cost of $1,500 a year.

They were travelling to Reyhanli in order to secure funds to pay for these, but instead, the couple found themselves destitute in a warzone.

“They didn’t even ask us to sign deportation papers but we were nonetheless lucky, we were not beaten,” said Zekeriya.

“Many people in the deportation centre were beaten when they begged guards not to deport them.”

The family’s arrival on 22 August in the Afrin region of Syria, which is under the control of Turkish-backed rebels, brought its own culture shocks.

According to Zekeriya, Bali was asked by rebels to cover her hair with a headscarf, but even more worryingly for the family, they had no place to stay.

“I am from Aleppo and my wife is from Algeria. We do not know anyone in Afrin. We had not been directed to any temporary housing, even to a camp.” Zekeriya said. “It was such a tough situation.”

“I found myself having to sleep in the street, and then I started posting videos of my distressing situation on social media,” Zekeriya added.

“Fortunately, a displaced civilian from Damascus came and welcomed us into a room in his flat, which had been damaged by [past] clashes."

The return

Days after the videos spread, Zekeriya received a phone call from a man who appeared to have a number associated with the Turkish state.

The caller identified himself as an official working on immigration issues in the Turkish capital of Ankara.

He took details of the family’s case and their residency in Turkey and asked that they not leave Afrin for the time being.

Meanwhile, Bali’s relatives had contacted the Algerian authorities on her behalf and there seemed to be tentative diplomatic support, but Zekeriya was still not optimistic.

“Many were promising quick solutions,” he said. “But locals told me that thousands of deportees were promised return [to Turkey] without benefit, including three people from Morocco who were stuck in Syria for eight months.”

Last year, Middle East Eye reported that three Afghans were stuck in northern Syria after being deported from Turkey.

“Fortunately, the rebels came on 27 August and asked us to accompany them to the border crossing,” Zekeriya said.

At the border they met an official he suspects was a Turkish intelligence officer, who he describes as “angry”.

The official allowed Zekeriya and his family back into Turkey.

Losing everything

But the family's troubles were not over yet.

While in Syria, Zekeriya’s videos had also attracted the attention of someone else - the landlord of his flat in Istanbul - who was worried about losing rent and contacted the beleaguered Syrian.

“He called and asked me if he could give the flat to new tenants, and I agreed. I thought I would be stuck for a long time like the others,” Zekeriya said.

As a result, the family lost their rented apartment and have been unable to afford a new one due to the cost of real estate agent fees, deposit and rent in advance.

'Our life has been completely destroyed and I don’t know what to do'

- Muhammed Zekeriya, Syrian refugee

Middle East Eye spoke to two government sources who are familiar with the case, who described the deportations as a mistake.

One said that the Turkish government would not send back anyone to Syria without them agreeing to do so voluntarily.

Another said that as soon as the mistake was realised, Turkish authorities acted to bring the couple back to the country.

“I now live in a shared flat for men, while my wife lives with the children in another shared flat for women,” Zekeriya said, describing his situation after his return.

“Our life has been completely destroyed and I don’t know what to do.”

He told Middle East Eye that he now plans to make the voyage to Europe by sea.

Zekeriya said that Turkish authorities do not care whether a migrant or refugee has the correct paperwork and he believes he could be deported again.

Despite condemning anti-immigrant sentiment, Erdogan is under pressure to appease the country’s far-right and has pledged to return a million refugees to Turkish-controlled areas of northern Syria.

Xenophobia

Syria remains a dangerous place for refugees due to the constant threat of conflict, as well as continued government persecution of dissidents.

The France-based Syrian Network for Human (SNHR) told MEE that the Syrian authorities had arrested 112 refugees who returned to Syria from Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan and Iraq from the start of the year through to September.

“Our reports and research indicate the continuation of violence and human rights abuses throughout Syria. Syria is still an unsafe country for the return of refugees, said Fadel Abdul Ghany, the founder of the SNHR.

“The forced deportation of any refugee from any country, whether Syrian or of other nationalities, is a violation of international law,” he continued.

“Contrary to what some Turkish media outlets broadcast that Syrian refugees affect the local economy, the bulk of the Syrians are funded by the European Union, and they help boost the Turkish economy.”

Expressions of anti-immigrant sentiments are not limited to arbitrary arrests and deportations but are also becoming increasingly common in public spaces.

In August, Arab media outlets reported the death of a Yemeni teenager, who was reportedly beaten to death after getting into a fight with a Turkish boy in Istanbul.

That same month, a Moroccan man was murdered by a taxi driver after an argument over the latter’s refusal to take a trip over a “short distance”.

While in both of these instances, the exact motivation remains unconfirmed, they help foster a climate of fear that migrants and refugees feel.

Additional reporting by Ragip Soylu in Ankara

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.