Egypt election: Another fait accompli for Sisi?

Egypt will hold a presidential election at the end of the year, with results expected by mid-December, or January in the event of a run-off vote.

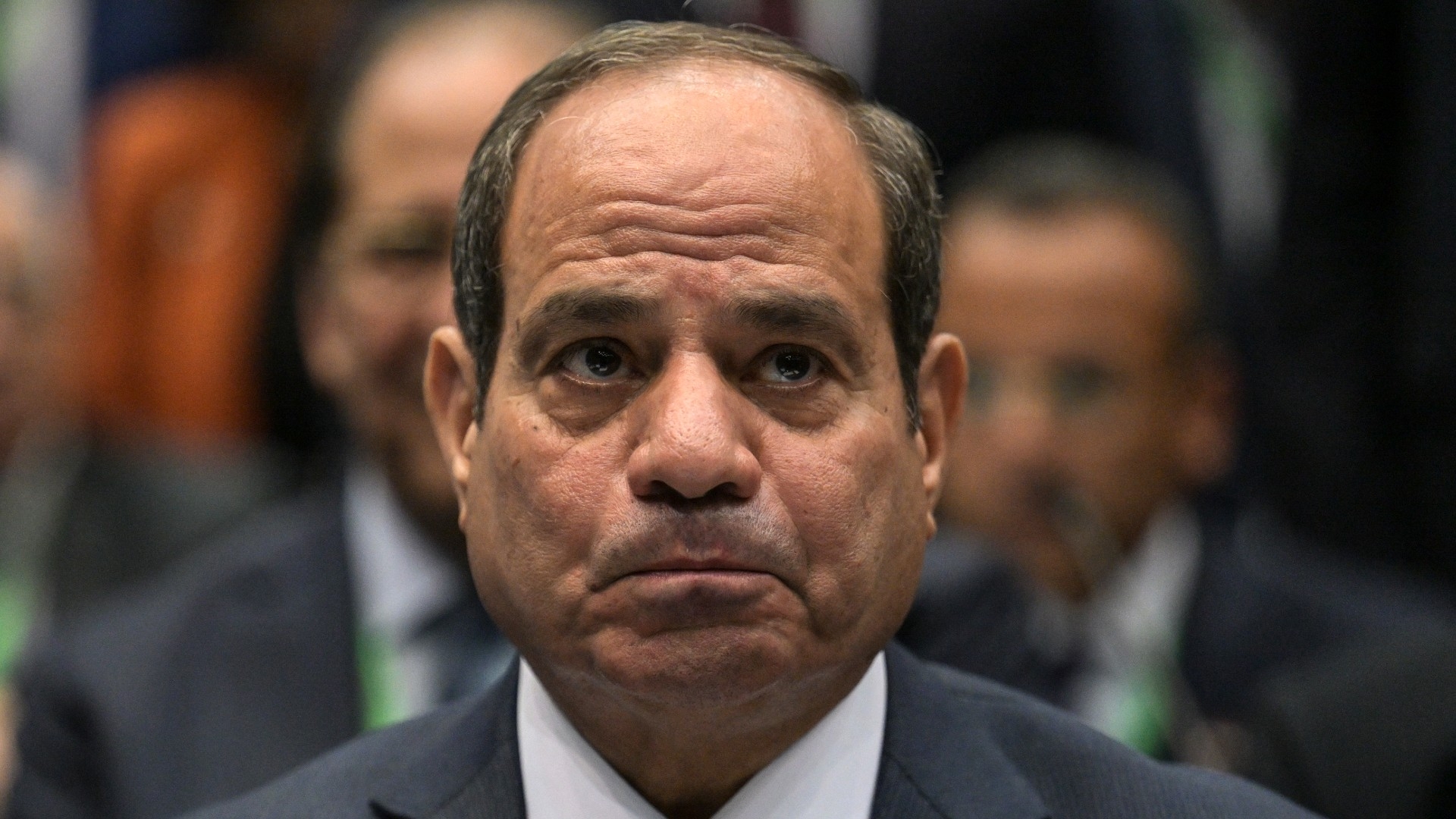

There is little suspense regarding the outcome: President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi will win.

Sisi, then the defence minister, led a military coup in the summer of 2013 against the country's first democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi. Riding the wave of mass fear and playing on the middle-class yearning for stability after the 2011 revolution, Sisi unleashed a bloodbath to pacify the country.

Simultaneously, he promised Egyptians economic prosperity and a rosy future ahead. The country became engulfed in Sisi mania, and there is room to argue he genuinely won the first post-coup presidential election in 2014, whether or not it was rigged.

From then on, Sisi's popularity plummeted, as he squandered billions on white elephants, repressed dissent of all shades, destroyed civil society organisations, militarised state organs, and impoverished Egyptians with successive currency devaluations, coupled with austere neoliberal policies that have left the economy in shambles, under the control of army generals.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Although flag-waving and national chauvinism are central to Sisi's public discourse, Egypt has lost much of its regional clout in recent years. The regime is dependent on continuous support from Arab Gulf despots, namely in Saudi Arabia, the UAE and, lately, Qatar.

In a move that left many feeling a sense of national humiliation, the regime gave up two strategic islands in the Red Sea to Saudi Arabia in exchange for financial backing. Egypt has also seen a sharp decline in relevance in its historical spheres of influence, such as Palestine and Sudan, let alone the other Nile basin states, where Ethiopia is threatening Egypt's water resources by erecting a dam, despite Cairo's vehement opposition to the plan.

Parallel chain of command

Sisi has made a mockery of the rule of law by controlling the judiciary, ensuring impunity for police and army killings, and amending the constitution to prolong his rule. Mega-prison complexes have been built to house a growing population behind bars.

Cabinet ministers and government executives are neither policymakers nor empowered to take initiatives. Instead, the country is micromanaged by Sisi, his sons and Major General Abbas Kamel, director of Egypt's General Intelligence Service (GIS), along with a cabal of officers. A parallel chain of command centres on active and retired army officers staffing all government departments.

The rationale among dissidents for contesting the election is simple: Sisi has killed politics and abolished any margins for organising in the streets or in cyberspace

In the previous two elections, in 2014 and 2018, Sisi was declared the winner with roughly 97 percent of the vote each time. And as expected, in recent weeks, Egyptian media outlets - which are mostly under the control of the GIS - have been publicising pro-Sisi endorsements from businessmen, state-dominated professional and labour syndicates, movie stars and singers.

Simultaneously, police have been distributing among the urban poor across the country basic consumer commodities, with Sisi's smiling face imprinted on each pack, serving as a tool for electoral propaganda.

On Monday, as the National Elections Authority announced the official start of the race, media outlets published photos of Egyptians "rushing" to local registrar offices to sign endorsements of Sisi. According to my labour sources, workers and civil servants have been bused in by their companies' management to take part in these endorsement charades.

From now until 8 November, the law stipulates that any candidate aiming to contest the election must either gather 20 endorsements from members of parliament (which is dominated by the regime-supporting Nation's Future party), or at least 25,000 citizens across 15 provinces, with a minimum of 1,000 in each province. This algorithm makes it almost impossible for any serious contender to challenge Sisi.

Lodging a protest vote

The demoralised and besieged activist community, and citizens in general, vary in their views on what's to be done. Some have called for a boycott, since the end result is already known. Building on that narrative, many contenders intending to run against Sisi are regarded with suspicion - as collaborators who must have struck some deal with the security services. Some politicians, who are staunchly pro-regime or have a history of collaboration with the state, surely fit that description.

Another stream among dissidents and the general population advocates taking part in the election, but lodging a protest vote for the "real" opposition. Here, things get trickier.

At the time of writing, there are three figures from opposition parties who have declared their intention to contest the election: Ahmed Tantawi, a former parliamentarian with the Nasserist Karama Party; Gameela Ismail, the head of the quasi-liberal Dostour Party; and Farid Zahran, the head of the Egyptian Social Democratic Party.

The most serious contender among the three is surely Tantawi. He is a seasoned politician from Kafr el-Sheikh province who was a source of annoyance for the regime when he was a parliamentarian. He lost his seat later, due to security services rigging the vote. He has publicly criticised Sisi and called on him to leave office, earning the dictator's wrath, which forced Tantawi to leave Egypt for Lebanon last year.

In exile, he announced his intention to run for the presidency, and returned to Egypt this past May. Since then, he's been laboriously building a campaign on the ground, despite repeated security crackdowns on his relatives and campaigners. Tantawi made international news recently when it was discovered that his iPhone was targeted with spyware (likely by the Egyptian regime), prompting Apple to deploy security updates to all its products.

Ismail and Zahran, meanwhile, were accused earlier this year of meeting with Egypt's spy chief, where the latter allegedly encouraged them to run in the election to provide a democratic facade. Both have denied the accusation. Discussions to unify the ranks of the opposition to rally behind one candidate haven't gone anywhere.

Sisi is almost certain to win this race, not because of his popularity, but because he wields the state's institutions and its fearful repressive apparatus. But the rationale among dissidents for contesting the election is simple: Sisi has killed politics and abolished any margin for organising in the streets or in cyberspace.

Now that the regime is weaker and less confident than it was a decade ago, thanks primarily to its economic blunders, the election offers a rare opportunity to revive - at least on a modest level - the ability to organise. Campaigners say this is one step on the long road towards reclaiming the streets.

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.