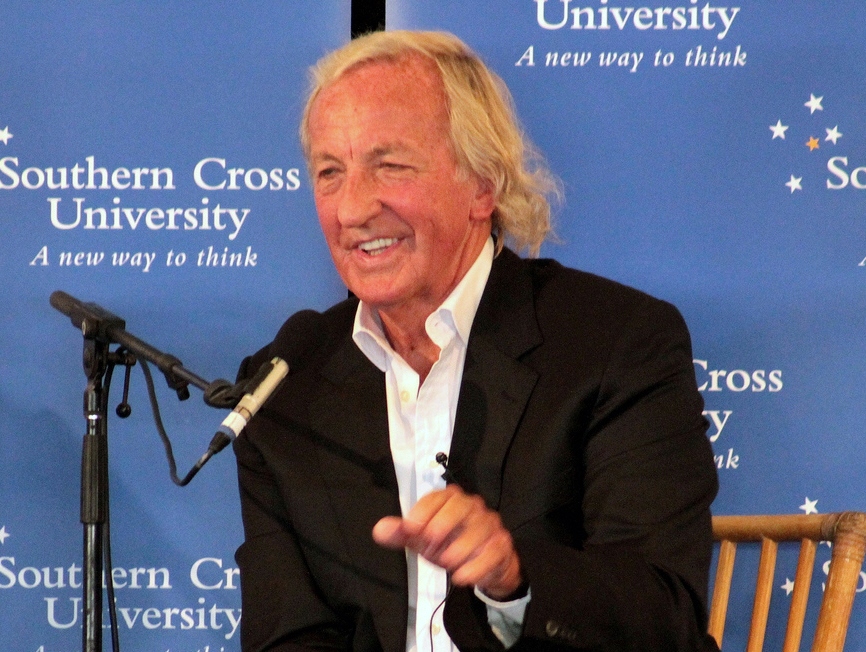

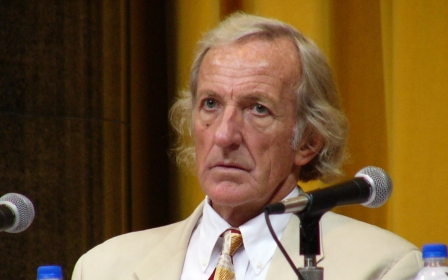

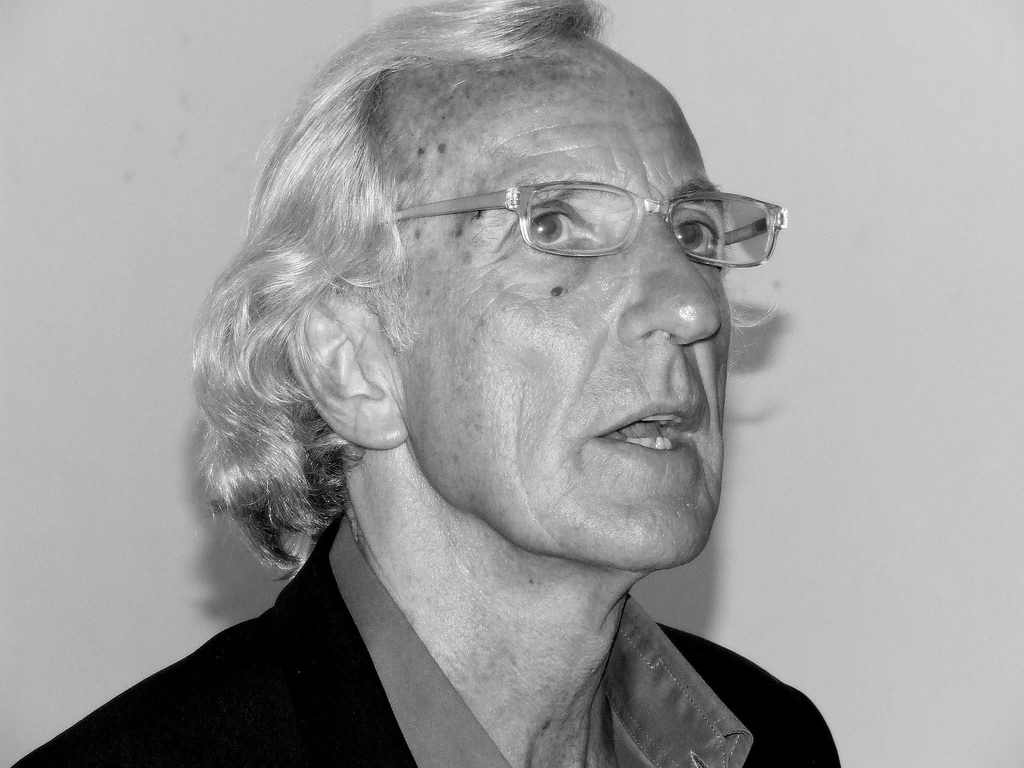

John Pilger: A life telling truth to power

David Munro, the brilliantly gifted director and producer of 20 of John Pilger’s 50 films and documentaries once wrote to him, “You opened my eyes and I thank you, since when they’ve never been shut.” No one knew Pilger better than Munro and their friendship continued even after Munro moved on to other personal projects, with John saying, “We never exchanged a harsh word.”

In the 23 years since his closest collaborator died, countless thousands of people who have watched Pilger’s films or read his books and articles have felt exactly that same sentiment of gratitude. Pilger was a brilliant communicator, a tireless reporter and researcher with an unparalleled record of near half century on the ground exposing the lies and cruelties of the West’s most powerful regimes, led by the United States, and their impact on people of the Global South.

Pilger’s Australian background and his early homes in journalism from Reuters and for 23 years at the Mirror, through ITV’s World In Action to latterly, the little-known Consortium News and CounterPunch, gave him a free-wheeling outsider status in UK journalism.

Original, brave, taking great personal risks, and extremely hard working, Pilger was never in the mainstream press pack. Perhaps it was partly because he was too famous and his high profile stoked jealousy. He won or was shortlisted for multiple BAFTAs and Emmy awards and in 1967 and and 1979 was journalist of the year.

In the 1960s he spent eight years between Vietnam and the US as the Mirror’s star writer. They were times of hectic intensity for any journalist. In Vietnam Pilger immersed himself in the catastrophe of the Vietnamese people under US bombing and the destruction of life, livestock and countryside by the poison of Agent Orange. In the US the stories were in the violence against the civil rights movement and the assassinations of US leaders heralding change, such as Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy. He looked back on Vietnam decades later as a “farce full of lies”. At the time it felt like an intolerable level of injustice and pain for people without a voice, who he, with the luck of being a journalist, would speak for.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Palestine and Cambodia

That was one pillar of the life experience which marked him indelibly as a young journalist. The second was staying happily on a kibbutz in Israel in the 1960s, but gradually seeing “the dehumanisation of Palestinians”. His 1977 film, Palestine Is Still The Issue, took on the great injustice of the illegal occupation of Palestinian land, and made him notorious.

His 1977 film, Palestine Is Still The Issue, took on the great injustice of the illegal occupation of Palestinian land, and made him notorious

Their historical adviser was a then little-known Israeli historian, Ilan Pappe, now the best known of academics on the subject in Britain. An industry enquiry ensued, and did not support the critiques. That truthful film, and the 2002 follow up with the same name earned John great and lasting respect in a much wider world.

Michael Green, then chairman of Carlton Communications and producer of the film, publicly disowned the 2002 film in a devastating and utterly unfair critique. Green set a tone which much of the mainstream media would use to harass Pilger throughout his career. “It was one-sided, it was totally unrealistic, but it was John Pilger….it was factually incorrect, historically incorrect,” he wrote as the Board of Jewish Deputies, Conservative Friends of Israel in Britain and the Israeli state responded with outrage to a serious film made by a careful and professional team.

The first two of his four Cambodia films, Year Zero: The Silent Death of Cambodia and Cambodia Year One, made with Munro and screened in 1979 and 1980, were revelatory of the horrors of Pol Pot’s rule and its aftermath and were very highly praised. The first helped raise £45m aid for starving Cambodians. But a 1980 visit with the films to the powerful distribution networks in the US gave Pilger a hard lesson. The executives were excited by the searing Khmer Rouge footage, but “no one wanted to show how three US administrations had colluded in Cambodia’s tragedy,” he later explained. And in the most bitter moment of this experience, at PBS the most liberal and independent of them all, the producer turned him down with, “your films would have given us problems with the Reagan administration – sorry.”

Two more great films in Asia followed in the 1990s - The Death of a Nation: The Timor Conspiracy and Inside Burma: Land of Fear. Pilger’s 1994 reportage and commentary on the former Portuguese colony of Timor Leste (until 1975), updated in 1998, was a particular highlight, a focus on a place shamefully unknown in the West throughout an Indonesian invasion and brutal military occupation which ended in 1999. When it was shown late at night on ITV the company received an unprecedented deluge of phone calls from the public.

Another decade, another war and another continent followed with Paying The Price: Killing the Children of Iraq (2000). Besides that heartbreaking film, Pilger was by then writing copiously and speaking for the anti-war movement in the UK, fired by opposition to the US-led Gulf War and then the Iraq war which, following western and UN economic sanctions, destroyed one of the Arab world’s best supporters of Palestine, and one of its most educated and culturally significant countries.

Kate Hudson, general secretary of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, describes Pilger as “a remarkable and incisive speaker on the anti-nuclear question, exposing decades of lies and hypocrisy about the impacts of nuclear testing and nuclear colonialism, in a profound and accessible fashion.”

Anticipating history

Three films show Pilger’s capacity for anticipating history. In 2004, Stealing a Nation, on Diego Garcia and the Chagos Islands, showed a virtually unknown corner of British colonial history: people displaced, successive UK government lies, the UK judiciary’s selective blind eyes. Eighteen years later, in February 2019, the International Criminal Court found the UK's colonial authority no longer legal in Diego Garcia. In 2016, The Coming War on China foreshadowed one of today’s world’s most dangerous political preoccupations. And, The Dirty War on the NHS made in 2019 gave a preview of today’s realities in the UK.

Over the decades, showings of his films in the British Film Institute’s largest cinema sold out, the showing always followed by a host of questions and his fans mobbing him on the way to the private reception. He wrote in UK papers and magazines across the board from the New Statesman via The Guardian to The Express, and later many more outlets across the world. His dozen books, including his expose of Australia’s political corruption and genocidal history in A Secret Country, have long lives.

Paul Rogers, Emeritus Professor of Peace Studies at Bradford University, said this week, “John was hugely effective in his extensive work on the realities of war and especially the often hidden social costs. To this add his numerous revelations involving western governments and interests that were so readily covered up. Then there is his consistent support for Julian Assange who had himself been so effective in revealing so many secrets of the war in Iraq.”

Journalists who wanted to shoot him down for his politics and his campaigning brilliance could never touch his decades of telling truth to power

For all his fame, Pilger was a rather private man embedded in tight loyalties to friends and his happy 30-year partnership with Jane Hill, a magazine journalist, and his beloved children Zoe and Sam. Many friends and acquaintances had their books and films endorsed generously and their lives enriched by John taking time for them. I remember many such occasions, one random night 23 years ago, for instance. We went to the Royal Court theatre in London because they had really wanted to have his opinion on a Palestine play, but had not liked to ask him for his time. He enjoyed himself, gave generous praise and modestly said he was honoured to have been invited.

In recent years John’s active support of Assange alienated him further from sections of the UK press who had long taken distance from Assange. And some of Pilger’s written judgements against mainstream opinion on complex world issues such as the real responsibility for the use of chemical weapons in Syria – with scientists taking opposing views - brought him harsh criticism. That modern war was very different from the on-the-ground reporting which had made his name. He was accused of being pro-Assad or pro-Putin. But Pilger never backed power in his life. And, like everyone, he made mistakes such as on Russian responsibility for the 2018 poisoning of the Skripals in Salisbury. Other journalists who wanted to shoot him down for his politics and his campaigning brilliance could never touch his decades of telling truth to power.

Role model

It is a fitting honour that The British Library holds the archive of Pilger’s huge work, accessible for history. New generations will learn there so much about the world seen from places like Nicaragua, Palestine, Cambodia, Timor Leste and Vietnam at firsthand, and also discover Washington decision-making in an unvarnished light.

One hot day in July 2005 perfectly sums up John’s life choices and reflects the very best of the private man who was my kind and loyal friend in hard times for four decades. That day his priority was attending a modest gathering in Jubilee Gardens by the river Thames far from any limelight. It was a memorial for the remaining veterans of the International Brigades, young volunteers fighting fascism from 1936 to 1939 in Spain, now all in their 80s and older. John read a poem to one of them, George Green, by his son who was four when his father was killed. Then he spoke of his debt to his late close friend Martha Gellhorn, the legendary American journalist of World War Two who was reporting in Spain in 1938. He read from one of her dispatches, saying that her experience taught him, “about moral courage, about speaking out, breaking a silence”. To the small group of elderly veterans in the red berets of their service, he said, “I thank you, and your fallen comrades, for what you did for us all, and for your legacy of truth and moral courage.”

In an echo of those sentiments, after Pilger’s death, professor Paul Rogers described him as “a role model of rare value”.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.