Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Who is Iran's supreme leader - and why does he matter?

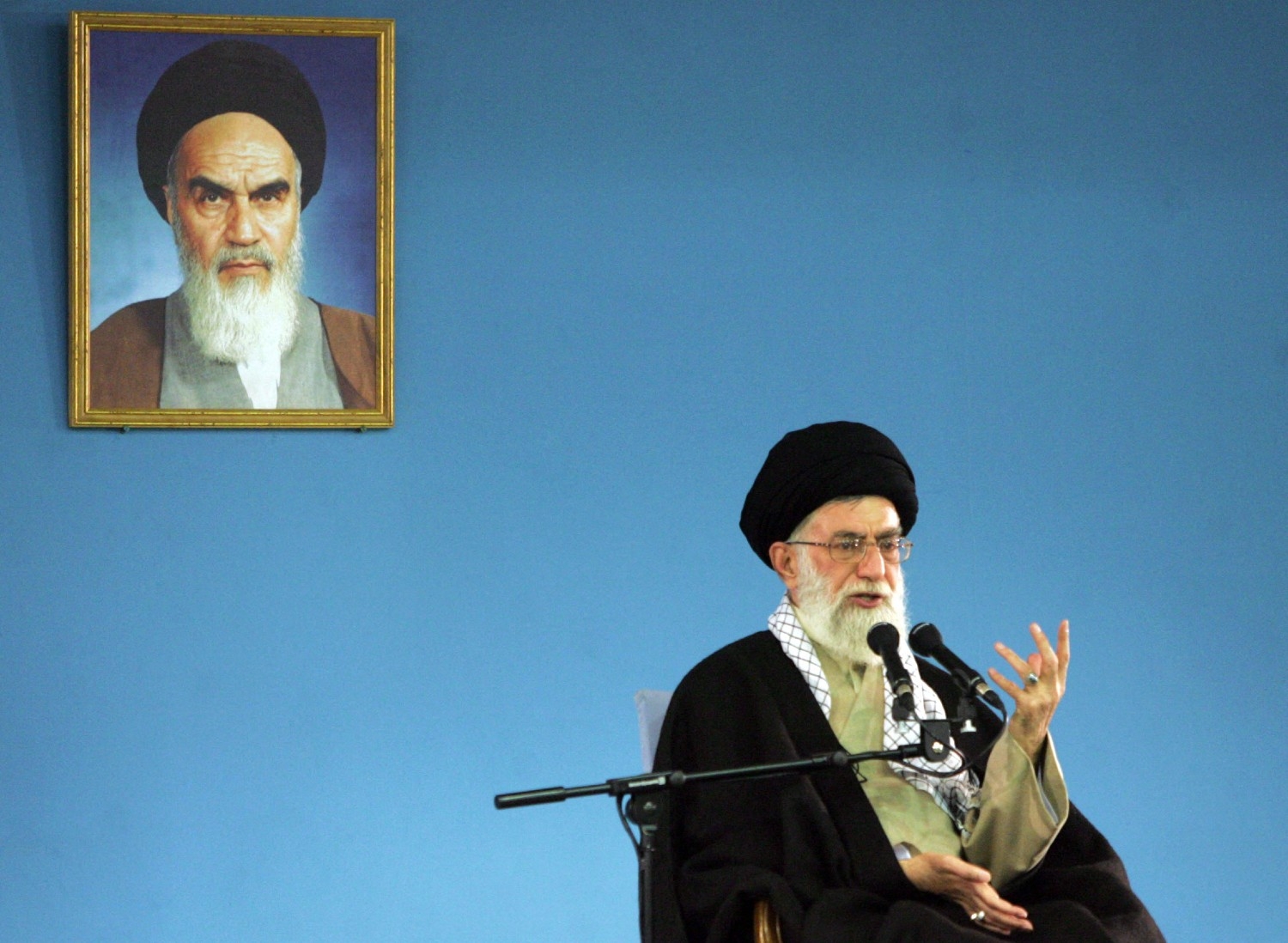

Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has been the key figure in Iranian political life for more than 40 years, and the country’s political and religious figurehead since 1989.

During that time he has presided over a nation that has undergone significant social and political change, and repositioned itself in the wider world.

Born into a clerical family on 19 April 1939, he undertook religious training at seminaries in the holy city of Mashhad, as well as Najaf in Iraq.

He returned to Iran and eventually settled in Qom, where he furthered his clerical studies under figures including Ayatollah Hossein Borujerdi and Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who was later to become the supreme leader.

During the 1960s and 1970s he participated in covert activities against the Shah, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, for which he was arrested and tortured multiple times by the SAVAK secret police.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In 1979, the Shah was overthrown after popular protests.

Khomeini, who had been in exile since the mid-1960s, returned to Tehran from France amid jubilant crowds and widespread support.

How did Khamenei rise to power?

Khamenei quickly ascended through the ranks of the early revolutionary state, assuming key roles on the Islamic Revolutionary Council, as well as a lawmaker and deputy defence minister. He also led Friday prayers in Tehran.

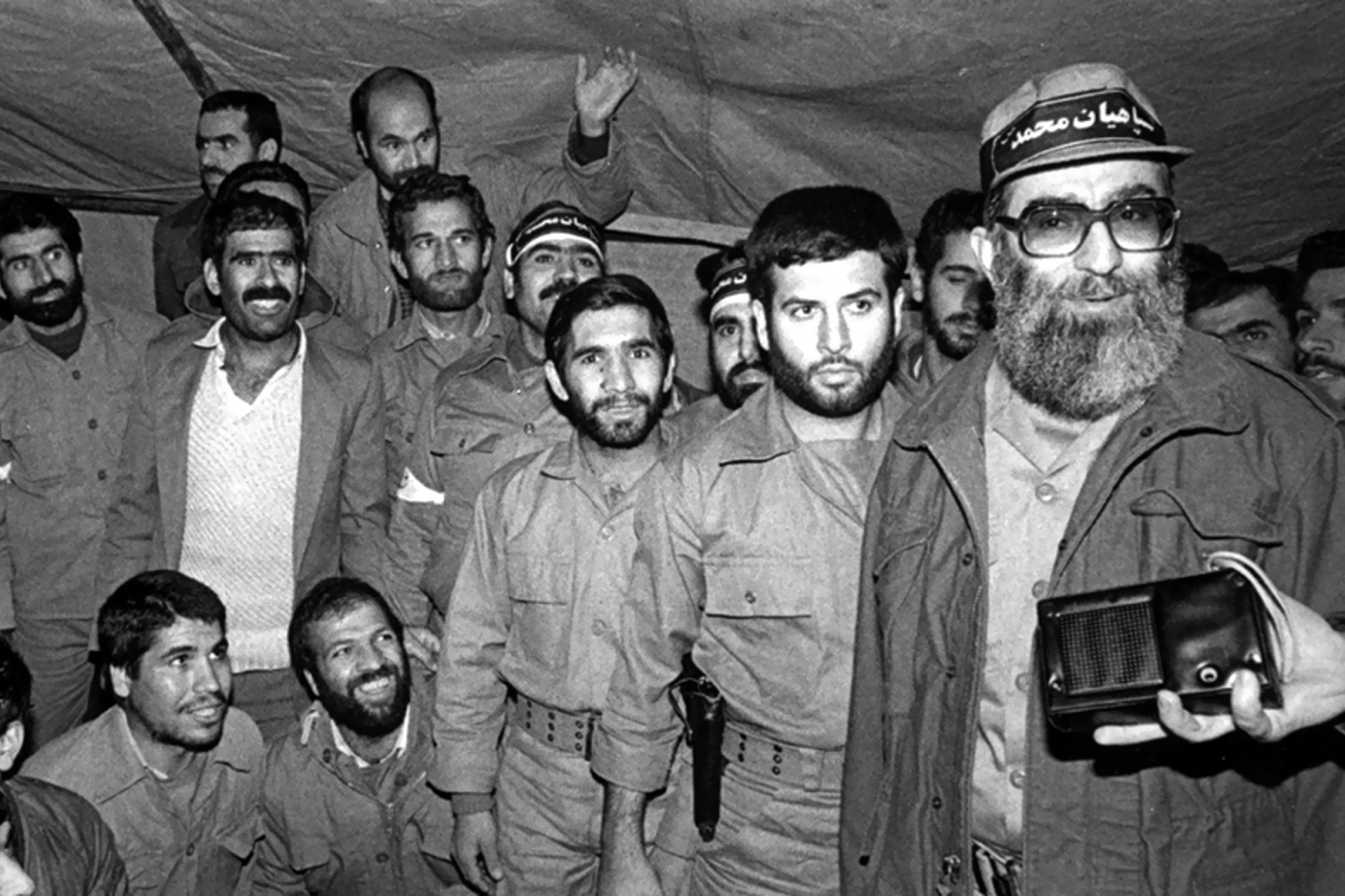

Khamenei was also one of the leading revolutionary figures targeted in assassination attempts in 1981, when a bomb hidden in a nearby tape recorder exploded as he was addressing a mosque. The attack was attributed to the anti-clerical opposition Forqan Group. Khamenei suffered serious injuries and was left paralysed in his right arm.

After President Mohammad Ali Raja'i and Prime Minister Mohammad Javad Bahonar were assassinated in August 1981 by the dissident Mujahedin-e Khalq (People's Mojahedin Organisation of Iran), Khamenei ran for the presidency, winning 95 percent of votes in an uncontested election.

He was publicly backed by the three other candidates, one of whom, Mir-Hossein Mousavi, was to become prime minister. Khamenei sought to cement the clerical establishment's control of the key organs of power, often clashing with more left-leaning figures, including Mousavi.

Khamenei’s foreign policy focused initially on managing Iran’s eight-year conflict with Saddam Hussein's Iraq, during which an estimated one million civilians and troops died on both sides.

In September 1987, Khamenei attacked the US presence in the region at the United Nations General Assembly in New York. “Our message to Third World governments is that as long as the order of domination and the current situation exists, they should try to create unity among themselves: this is the best way to become powerful.”

How did Khamenei become supreme leader?

In 1989, the world changed with the end of the Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union.

Iran also began to witness significant changes. The death of Khomeini on 3 June 1989 was a crucial turning point for the country. Khomeini’s long-time designated successor, Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, had been sidelined and effectively defrocked by Khomeini only three months earlier, due to his calls for more pluralism in politics.

Iran’s Assembly of Experts designated Khamenei as Iran’s new leader, a role which Khamenei himself initially argued he was not qualified to assume.

Khomeini’s theory of Islamic government, on which the Islamic Republic’s political system was partly based, centred on the notion of the guardianship of the jurist, known as velayat-e faqih. It asserts the power of the clergy over the state, and means only the highest-ranking Shia clerical figure is deemed sufficiently qualified to be Iran's supreme authority.

But Khamenei’s position in June 1989 was only that of a middle-ranking hojatoleslam. For some clerics, Khamenei was not sufficiently qualified in religious matters to hold the post. Khamenei himself asserted as much in his inaugural address, noting that he was but a “minor seminarian”.

Subsequent changes to the constitution stated that it was more important for the office holder to be “aware of the times”, and therefore politically minded, rather than derive their authority solely from certain religious qualifications. At the same time, the executive powers of the presidency were also enhanced.

Khamenei’s unconventional assumption of power eventually led to a form of dual leadership between him and Ali Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani, president from 1989-1997.

During the early years of his rule, the two long-time protagonists in Iranian post-revolutionary politics initially acted in step with one another.

Have there been any challenges to Khamenei?

Khamenei has faced opposition, both within the establishment and, perhaps more seriously, among the wider population. But his position at the time of writing seems secure.

The relationship between the presidency and supreme leader came under increasing strain during the 1990s, as the liberalising tendencies of Rafsanjani collided with the conservatism of Khamenei.

Khamenei’s relative pragmatism was especially tested with the rise of the liberal reformist movement in Iranian politics from the mid-1990s onwards.

This reached its zenith with the election of Mohammad Khatami as Iran’s fifth president in 1997. Khatami rode a wave of popular optimism and secured support from Iran’s rapidly growing young population and female voters.

Khamenei now adopted a more recognisably conservative outlook, often acting as a balance against the more liberally inclined Khatami. This approach also extended to curtailing reformist efforts to further open Iran to the West.

When Mahmoud Ahmadinejad became president in 2005, the assumption was that he and Khamenei would be in lockstep, due to Ahmadinejad’s popularity among Iranian conservatives.

Nowhere was this more apparent than following the disputed 2009 presidential elections, when Ahmadinejad controversially secured a second term with Khamenei’s support. The ayatollah's authority was challenged by popular protests in support of defeated candidates, Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, and the rise of the Green Movement.

The demonstrations marked some of the most open displays of dissent against the Islamic Republic’s rulers since the early years of the revolution. Lesser demonstrations, against economic conditions, took place in 2017 and 2019.

The most recent widespread signs of discontent in Iran during Khamenei’s reign began in autumn 2022, after Mahsa Amini, 22, died from her injuries after being detained by the "morality police" for allegedly wearing her headscarf "improperly".

Widespread protests followed, both at Amini’s funeral and subsequently, lasting several months and resulting in the deaths of hundreds of people. At times, some demonstrators called for Khamenei to go.

In October 2022, Khamenei argued that the protests were not about the death of Amini or wearing of the hijab but the involvement of foreign governments. “It is about Islamic Iran’s independence, resistance, strength, and power," he said. "That is what this is about.”

How did Iran reach a deal on nuclear issue?

Iranian electoral politics swung back towards a more moderate outlook when Hassan Rouhani became president in 2013.

Khamenei reasserted his authority against his president, but also gave his consent for Rouhani to pursue a more pragmatic foreign policy.

Much of this focused on the attempts of foreign powers to stall Iran’s nuclear ambitions, an especial cause of tension between Tehran and Washington which had resulted in crippling economic sanctions against Iran for much of the past decade.

Khamenei initially allowed Rouhani and his negotiating team considerable power: as secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, he had led nuclear talks with key EU powers between 2003 and 2005.

Discussions eventually came to fruition with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action in 2015. One year later, sanctions were lifted.

Khamenei cited the need to demonstrate “heroic flexibility” in the negotiations. At the same time, he imposed strict limits on Iranian concessions to world powers in the agreement. Later, he accused the US of reneging on its commitments, saying: “The nuclear deal, as an experience, once again proved the pointlessness of negotiating with the Americans, their bad promises and the need not to trust America’s promises.”

US President Donald Trump’s subsequent violation of the deal in 2018 was seen by Khamenei as proof that the US could not be trusted, and set the stage for a sharp downturn in Iran’s relations with the US and some of its key allies in the region.

Despite offering conditional support for a return to the JCPOA, talks aimed at reviving the deal under the presidency of Joe Biden have been put on ice since 2022.

What does Khamenei think of the rest of the Middle East?

Multiple conflicts have destabilised the Middle East during the past decade, most notably in Syria, a key Iranian ally, where Iran-aligned groups have had a key role in enabling President Bashar al-Assad to restore control over most of the country.

For Khamenei, the Arab uprisings of 2011 were a chance to invoke an “Islamic Awakening” across the region, for which Iran could act as a potential model of Islamic government.

But the ensuing conflicts that resulted exacerbated long-standing geopolitical rivalries, none more so than between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Up until their 2023 rapprochement, the kingdom was regularly chided by Khamenei for its culpability in regional conflicts, its close relations with the US, and more recently its increasingly open convergence with Israeli interests.

Khamenei viewed many contemporary developments as due to perceived anti-Iranian forces, as illustrated by the emergence of the Islamic State (IS) group as a significant existential security threat to Iran.

In recent decades, Khamenei has established Iran as the hub of the Axis of Resistance, using the military nous and operational expertise of its elite Quds Force under the leadership of the assassinated Qassem Soleimani to enhance its strategic depth and counter threats against the Islamic Republic.

The axis has drawn in allies at state and sub-state levels from across the region, all of whom share Khamenei’s worldview of an independent region expunged of US forces.

"The policies of America in the region are 180 degrees apart from the policies of the Islamic Republic," he said in 2015.

Iran's conception of the axis includes Syria, Hezbollah in Lebanon, allied factions of the Iraqi Popular Mobilisation Forces and Yemen's Houthi movement. Palestinian groups, including Hamas, Islamic Jihad and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine are also seen as key members.

It is this project that perhaps will be seen as one of Khamenei’s most significant legacies, and one that has already left an indelible mark on regional politics.

What does Khamenei think of Israel?

Iran-Israel relations have been contentious since the founding of the Islamic Republic, with Khomeini declaring the last Friday of Ramadan as “Qods Day”, a pro-Palestinian day, reflecting his opposition to recognition of Israel’s legitimacy as a state.

Iran’s support for the Palestinian cause has been a long-standing feature of its foreign policy, forming a regular theme in Khamenei’s pronouncements on Iran’s international relations.

For the broader Axis of Resistance, Palestine-Israel remains a central focus, acting as the key element in its “unification of arenas” concept, whereby Iran and its allies have begun to foster ever-closer coordination in their confrontation with Tel Aviv.

Israel and Iran have been involved in an escalating shadow war for many years. Israel has regularly targeted Iran and allied figures in Syria and Lebanon, as well as being responsible for a number of attacks on Iran’s nuclear programme.

Up until April 2024, Iran had largely followed a policy of what it termed “strategic patience” in response to the targeting of its interests, and continued to avoid direct confrontation with Israel, given its ongoing assault on Gaza.

However, the launch of several hundred drones and missiles against Israel on 13 April, in response to its bombing of Iranian diplomatic premises in Damascus on 1 April, marked a “new equation” in Iran’s approach to its nuclear armed rival.

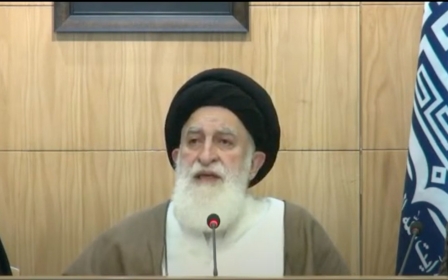

Who will succeed Khamenei?

Given Khamenei’s age, speculation is naturally rife around who might become his successor.

Some point to a possible dynastic succession involving his son, Mojtaba, while others have cited President Ebrahim Raisi as a potential candidate.

With reformist and even pragmatic conservative voices increasingly sidelined in Iranian politics, it seems most likely at present that Khamenei’s successor will come from the harder end of the conservative camp, although the appeal of more unifying candidates being involved in the process cannot be discounted.

Whatever happens, the role of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) will be key, given the huge political and economic power it wields. It is no surprise that one of Khamenei’s key achievements has been the role that he has permitted the IRGC to assume for itself in Iran’s domestic politics and foreign policy.

Regionally, the IRGC has been the primary actor in reinforcing and expanding Iran’s strategic depth, playing a major role in shoring up its national security, while entrenching its position domestically.

As such, Khamenei has overseen the development of an ever deepening security apparatus at home. While he has been perhaps the key figure in ensuring the Islamic Republic endures, the tensions between those who seek to challenge the totality of its rule through greater freedoms, and those who wish to guard it, will continue to shape Iranian political and social life under any successor.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.