Sudan war: Revolutionary movement plots path to peace

Early in April, leaders of Sudan's radical revolutionary group Anger Without Borders met with Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, chief of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the country’s de facto ruler.

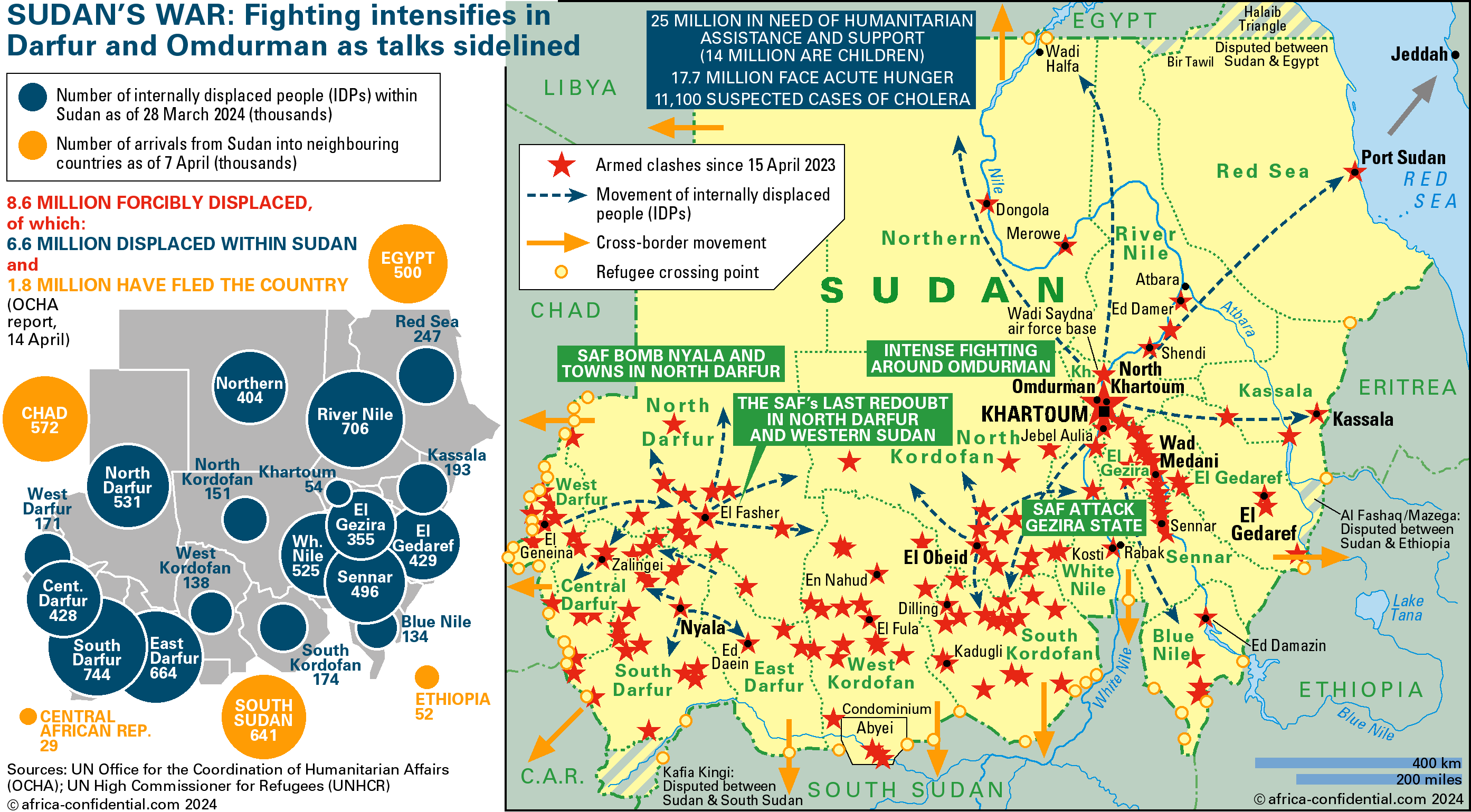

Members of the group had been fighting alongside the army in its war against the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which has been ongoing since 15 April last year, claiming the lives of tens of thousands of people and displacing over eight million Sudanese from their homes.

But while Anger Without Borders had taken up arms alongside the army, its meeting with Burhan started an argument on social media. Burhan, after all, was the man who, along with Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, the RSF chief better known as Hemeti, had orchestrated the military coup of October 2021 that blew up Sudan’s transition to full civilian leadership.

And so, Anger Without Borders was accused of seeking to legitimise military rule in Sudan through its meeting with Burhan who, over the Eid al-Fitr holiday of 10 April had announced that his aim was not to return the country to any kind of civilian government.

Appearances, though, can be deceptive. What really happened, according to group member Nuha Abdul Gadir, who spoke to Middle East Eye, was an ambush. The revolutionaries had been set up as part of a “piece of propaganda”.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“The members of Anger Without Borders were summoned for a normal meeting, then suddenly found themselves in a room with Burhan. Our leaders tried to leave but the soldiers prevented them. They were lured there so Burhan could be photographed with them,” Gadir told Middle East Eye.

'We can’t put our hands on the hands of Burhan, which have been dirtied by the blood of the revolutionaries'

- Nuha Abdul Gadir, Anger Without Borders

“We can’t put our hands on the hands of Burhan, which have been dirtied by the blood of the revolutionaries. Our leaders joined the army to defend our people from the violations of the RSF,” she said, specifying that fighting the RSF was not the same as fighting for the army, and referring particularly to the army and RSF-led operations against protesters in 2019, which left hundreds of civilians dead.

With Sudan’s war now more than a year old, the country’s revolutionary movement, as well as its technocratic civilian leaders, has been trying to forge a pathway to peace that does not end up solidifying military rule.

Sometimes, this has meant taking difficult decisions, with different civilian actors seeming to offer support to one or other of the warring parties. The army is now made up of a constellation of different groups representing wildly diverging ideologies, from radical revolutionaries to ultra-conservative Islamists.

Many of those groups see the army as a means to an end: namely, defeating the RSF, which international human rights groups have concluded is committing genocide against “non-Arab groups” in Darfur, the vast western region of Sudan that serves as its powerbase.

Heart of the revolution

The resistance committees - nationwide groups of local activists that have been at the heart of Sudan’s revolutionary movement - have, along with the affiliated emergency response rooms (ERR), been organising lifesaving wartime support across Sudan, and are actively trying to bring the war to an end.

In a document titled, “The political vision to end the war in Sudan,” the resistance committees have detailed their bottom-up approach to solving the crisis in Sudan through political pressure and popular organising. This stands in contrast to the approach taken by technocratic civilian actors like former prime minister Abdalla Hamdok’s Taggadum coalition, which is seeking to convince the warring parties to head back to the negotiation table.

The next round of US- and Saudi-mediated ceasefire talks, scheduled to being in Jeddah, are now no longer happening.

At a recent conference in Paris, the international community pledged $2bn in aid for Sudan. Neither the SAF nor the RSF was invited to take part in the conference, which was attended by Sudanese civilian actors.

The resistance committees have expressed doubts over the commitment of international donors and hit out at world actors for “forgetting” the crisis in Sudan.

A leading resistance committee member from Gezira state told MEE that the groups’ roadmap called for the dismantling of the RSF and the creation of a new army that would stay out of Sudan’s politics and allow the building of full civil rule.

The source, who asked for anonymity for security reasons, said this would not be possible under the SAF’s current leadership, which is against the revolution and against civilian rule.

“The question of how to build a new army is the main challenge for the war in Sudan. We are working with retired officers and officers who have been dismissed to formulate the creation of a professional army that accords with the process of disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration,” he said.

“We believe that junior army officers, who have no interest in continuing the war, will stand with our vision.”

The resistance committee leader said they were against the RSF “and against the leaders of the SAF who failed to protect the people. We also warn the elites that are supporting the militias and foreign countries that are supporting the militias to stop what they are doing”.

The United Arab Emirates is the RSF’s main patron, while Africa Confidential has reported that the army has been operating Iran-supplied drones, notably the Mohajer-4 and Mohajer-6, since January.

Middle East Eye recently reported on Russia’s role in the war, as Moscow moves to play both sides, strengthening relations with the army while continuing to facilitate the supply of the RSF through the Wagner Group.

“Our roadmap also includes the formation of revolutionary governments from the grassroots in different states after the design of new interim constitutions through a dialogue between the Sudanese people,” the resistance committee source said.

'Impossible balance'

Muzan Alneel, a Sudanese scholar, described the resistance committees as the only genuine democratic group to face the militarisation of politics in Sudan.

“The success of the resistance front in advancing its position was captured in the slogan of the ‘Three Nos’ - no negotiations, no partnership, no legitimisation - against the military council,” Alneel, co-founder of the Innovation, Science and Technology Think-tank for People Centered Development, told MEE.

'We believe that junior army officers, who have no interest in continuing the war, will stand with our vision'

- Resistance committee leader

In the period leading up to the beginning of the war in April 2023, this slogan was chanted at protests and, Alneel said, even the civilian Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC) coalition, made up mostly of technocratic, elite politicians, “felt compelled to include it at the bottom of their statements”.

However, the argument the resistance committees made – that “the latest coup would only encourage further violence and perhaps even a war” was, Alneel said, ignored by international political and media organisations.

“For the two warring entities - both of which had expanded their influence using violence, massacres, and coups, and faced no consequences other than further legitimisation - it was only logical to attempt a full takeover via further violence," Alneel told MEE.

But she criticised the resistance committees for now supporting the army to protect the state, saying they had “attempted to strike an impossible balance between calling for an end to the war and supporting the army of the coup government”.

“For months, they attempted to hold together two contradictory goals: namely, the revolution’s goal of protecting and prioritising human life, and the counter-revolution’s goal of protecting the state,” Alneel said.

“The counter-revolution, boosted by decades of bourgeois propaganda promoting patriotism over human life, appears to have defeated the revolution,” she said.

Situation on the ground

Facing little real pressure from the outside world, both sides have escalated the fighting, with the army targeting Khartoum and Gezira states.

There is fierce fighting in el-Fasher, the capital of North Darfur, where there are fears that the RSF could massacre non-Arab civilians. Across Darfur, there is already "clear and convincing" evidence that the RSF is committing genocide.

Currently, according to a military analyst monitoring the battle, the RSF is maintaining static positions around el-Fasher, with clashes and exchanges of artillery taking place in the northern and eastern sectors of the city.

For the first time since the war began over a year ago, there is fighting in River Nile state.

Former rebel movements from Darfur and Blue Nile are fighting alongside the army and they have shifted the balance of power slightly, advancing towards Gezira state, which has been under RSF control since the paramilitary stormed through it in December, meeting little army resistance.

The army is laying siege to the RSF-controlled al-Jili oil refinery north of Khartoum, alongside rebel fighters from Darfur governor Minni Minnawi’s Sudan Liberation Movement.

“The pro-SAF Darfur rebels are fighting hard in al-Jili and Gezira but not really making advances. There are serious coordination issues between the SAF and rebel groups,” the military analyst said.

“We are besieging the RSF in al-Jili around the Khartoum oil refinery and we believe that its seizure is only a matter of time for us. We have destroyed 37 vehicles and captured 18 others from RSF,” Alsadig Alnur, a spokesperson for the SLM/ Minnawi faction, told MEE earlier this month.

The former rebels of another faction of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, led by the deputy head of the Sovereign Council, Malik Agar, are advancing from Sennar state towards RSF-controlled areas in the south of Gezira state. Eyewitnesses told MEE there had been fierce fighting in Wad Alabas, eastern Gezira.

The war has devastated Sudan. According to the UN, almost 25 million people will be in need of humanitarian assistance in 2024, while 8.8 million have been displaced from their homes.

Mass killing, rape and sexual assault, theft and looting have all been widespread, as the Sudanese people struggle to see an end to the bloodshed.

Additional reporting by Oscar Rickett.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.