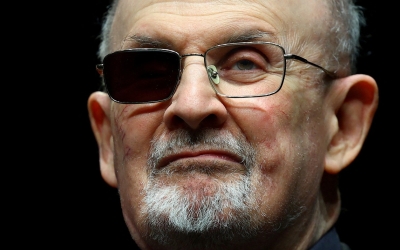

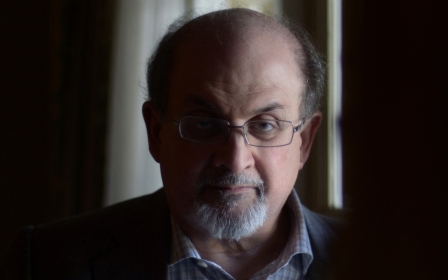

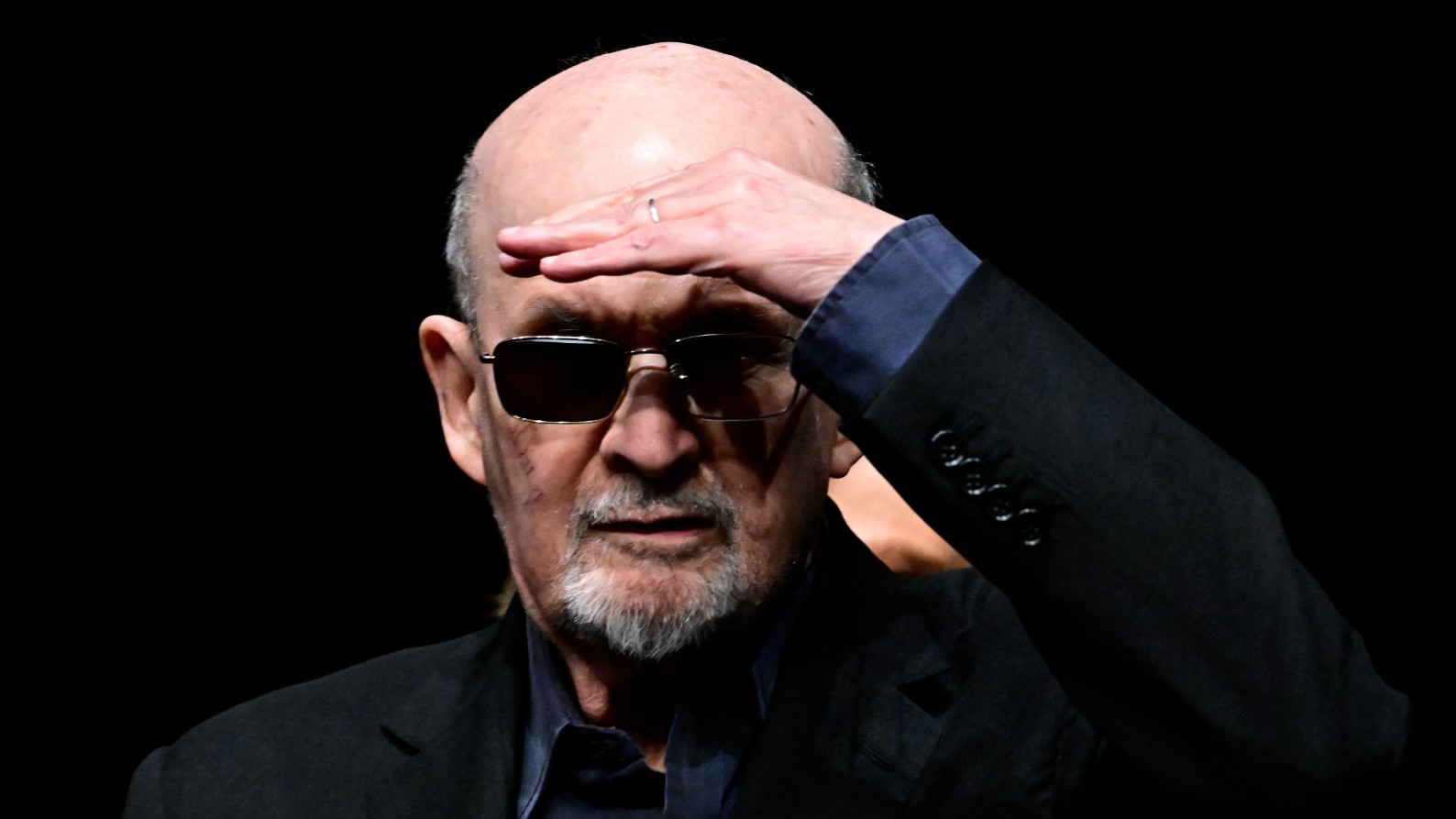

Salman Rushdie is echoing Israeli talking points to justify the horrors in Gaza

A university lecturer in postcolonial literature once told me about the two occasions he had met Salman Rushdie.

On the first, in the early 1980s, Rushdie had recently shot to fame with his blockbuster novel Midnight’s Children, which won the 1981 Booker Prize and sold over one million copies in Britain. Rushdie, my lecturer told me, was affable, loquacious and charming.

The second occasion came after Rushdie’s 1988 The Satanic Verses, followed in 1989 by a fatwa issued by the Iranian leader Ayatollah Khomeini, declaring the book heretical and calling for the killing of Rushdie.

Understandably, this experience, and that of living in hiding for several years, had changed him; perhaps there was also an element of the literary superstar status which had accrued to Rushdie, only boosted by the fatwa. Whatever the reason, this time, my lecturer found Rushdie to be aloof, cold and condescending.

I’m reminded of this transformation by another transformation Rushdie has undergone: on the question of Palestine.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In May, in an interview with German broadcaster Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg, Rushdie condemned student protests in solidarity with Palestine as “slid[ing] into an antisemitic discourse… in many cases”, and cynically dismissed calls for a cultural boycott of Israel as “a universal problem”.

He continued that while “any normal person can only be shocked by what is happening in Gaza right now, by the extent of innocent deaths, I think the demonstrators could also mention Hamas. Because it all started with them.

"And Hamas is a terrorist organisation. And it’s funny that a young progressive student policy supports a fascist terrorist group, because that’s what they do in a way. They demand ‘free Palestine’, liberate Palestine.

“I have been in favour of a Palestinian state for most of my life," he continued. "But if there were a Palestinian state now, it would be run by Hamas and we would have a Taliban-like state. A satellite state of Iran. Is this what the progressive movements of the western left want to create?”

Falling into line

Just like that, Rushdie fell into line with the consensus among the West’s pro-Israel political elites (nowhere more pronounced than in Germany, the country of his interviewers).

He could have paid tribute to students who have put their studies and future careers on the line, and faced violence from police and pro-Israel counterprotesters in response.

He could have acknowledged the 76 years of Israeli apartheid, colonisation and dispossession of Palestinians, rather than claiming that “it all started” with the Hamas attacks of 7 October 2023.

And he could have spoken out more forcefully against Israel’s carpet-bombing of Gaza, starvation of its population, and damaging or destroying all of its universities, alongside killing over 35,000 Palestinians.

Instead, he merely echoed hollow Israeli talking points, the underlying purpose of which have been to justify the horrific devastation of the Gaza Strip.

Rushdie was not always so dismissive of the Palestinian cause. His conversation with the Palestinian-American political activist and cultural critic Edward W Said, held at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in September 1986, stands as one of the most engrossing and enjoyable interviews of the 20th century.

The credit lay mainly with Said, who had recently authored his lyrical and powerful After the Last Sky, which Rushdie accurately described as “a passionate and moving meditation on displacement, on landlessness, on exile and identity”.

Rushdie provided Said with a sympathetic page on which to write his narrative.

The Rushdie-Said interview was recently screened at the ICA, as part of a day of solidarity activities for Palestine. The audience laughed at Said’s cutting takedowns of laughable Israeli propaganda from the 1980s and applauded at the end of the video.

There were, too, weary sighs when - ironically, given his recent statements - Rushdie complained of “the difficulty in making any kind of critique of Zionism without being instantly charged with antisemitism”.

Bad-faith arguments

While that difficulty hasn’t changed, Rushdie’s own politics certainly have. In the years following the fatwa, Rushdie was turned into a cause celebre for western politicians with an Islamophobic and imperialist agenda. Rushdie gave his support to the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and became a figurehead for neoconservatives and right-wing agitators who argued that Islam was a threat and the West was a superior civilisation.

An element often overlooked in the case of Khomeini’s fatwa was that dozens of intellectuals from the Islamic world leapt to defend Rushdie against the attack on his freedom of speech and his safety.

Follow Middle East Eye's live coverage for the latest on the Israel-Palestine war

In 1994, the collection For Rushdie: Essays by Arab and Muslim Writers in Defense of Free Speech included contributions by several Palestinians, including the eminent writers Mahmoud Darwish, Emile Habibi and Said.

The essay “So Be It” by Palestinian filmmaker Michel Khleifi retains perhaps the most resonance. Writing that “I am against double standards”, Khleifi pointed out that to be in support of “complete and absolute freedom of expression, to dignity” should also mean support for “the people’s emancipation - and the Palestinian people also have the right to dignity”.

After the fatwa, Rushdie was turned into a cause celebre for western politicians with an Islamophobic and imperialist agenda

He continued: “One question bothers me: these politicians, religious leaders, these men who hold the power, have they forgotten that they were once young, that they had dreams and doubts and all other kinds of problems with the outside world?”

Rather than hypothesising what form a Palestinian state might take, and ultimately repeating the same bad-faith arguments that Benjamin Netanyahu and countless other Israeli politicians, security personnel and commentators make to justify their denial of Palestinian freedom, and the indefinite perpetuation of occupation, Rushdie could listen to a rising generation of Palestinians.

Journalists from Gaza, such as Bisan Owda and Motaz Azaiza, and the East Jerusalem poet Mohammed el-Kurd, are hardly the mouthpieces of a Taliban-like state in waiting. Rather, they give voice to the dreams and frustrations of Palestinian youth, who have known nothing but occupation, apartheid and now genocide for all of their still-short lives.

It is a shame that Rushdie, with his prodigious imagination, cannot imagine himself in the place of these Palestinian youth. Nor can he imagine a free Palestine that is independent, peaceful and prosperous.

With the recognition of the state of Palestine by Ireland, Norway and Spain, Rushdie is falling out of step even with many western governments, and increasingly echoes the hard right he once decried.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.