Is Israel going the way of the Crusaders?

In July 2023, I completed what was supposed to become the fourth edition - and third update - of my book, The Gun and the Olive Branch: The Roots of Violence in the Middle East, a history of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Then came 7 October, Hamas’s murderous rampage through southern Israel, and the dramatic, potentially cataclysmic developments, political and otherwise, that it has set in train.

Not to bring these developments into my update would have been absurd, but to do so very problematic, and I decided not to attempt it. I think, however, that the prologue and epilogue of the aborted new edition remain valid, and relevant, on their own.

Here they are, unchanged except for 13 additional words - “and it [Israel] is making one helluva job of that in Gaza right now” - in the last paragraph.

Editor’s note: The following was written prior to 7 October 2023.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Prologue

"Will we always live by the sword?"

- Levi Eshkol, Israel’s then-prime minister, addressing pro-war members of his cabinet on 28 May 1967.

“Yes.”

- Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, speaking to the Knesset foreign affairs and defence committee on 26 October 2015.

In the late 1960s, a literary agent asked me for a book about an important new development in what already ranked as one of the world’s longest-running and most dangerous conflicts, that between Arab and Jew in the Middle East.

This was the rise of the Palestinian “resistance” movement, in the shape of Yasser Arafat’s Fatah and a host of lesser such organisations, remnants of which remain, in much reduced and decadent forms, in operation till this day.

Follow Middle East Eye's live coverage of the Israel-Palestine war

They deemed themselves freedom fighters, bent on the “return”, through “armed struggle”, to their ancestral homeland, Palestine. The Israelis called them “terrorists” bent on the “destruction” of their newborn state. And indeed, “terrorists”, in much of what they did, they clearly were.

It was with one of the most sensational, high-visibility terrorist exploits of all times, the hostage-taking and killing of 11 Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics in 1972, that they shocked the world - and reinforced an almost universally dominant western orthodoxy: that, in this conflict, Israelis were the righteous ones, Palestinians and Arabs the unrighteous.

Theirs was the Violence of my subtitle. Its Roots, however, lay mainly in the violence of the other side.

Recounting all this took me from its first faint, premonitory tremors in the 1880s - via the steadily escalating affrays between Palestinian peasants and newly arrived Jewish settlers of the early 1900s; the inter-communal rampages of the 1920s; the terrorist campaigns of the 1930s and ’40s, pitting Arabs against Jews but, to far greater effect, Jews against both Arabs and British Mandatory authorities; and the expulsion of the bulk of the Palestinian population in 1947-48 - to the serial, seismic convulsions of four full-scale Arab-Israeli wars in the first 25 years of Israel’s existence.

First update: 1976-1983

This seven-year period saw the first-ever Middle East peace agreement between Israel and its most powerful neighbour, Egypt, in 1979, followed by Israel’s invasion of its weakest one, Lebanon, in 1982, and the expulsion from it of Arafat’s guerillas.

It also saw what subsequently came to be quite simply known in the Middle East - rather like Bergen-Belsen or Babi Yar in Europe - as “Sabra and Shatila”, the genocidal slaughter that the Phalange, a Lebanese Christian militia, under Israel’s control and its army’s very noses, visited on the women and children, and older men whom the departing guerillas had left behind, wholly defenceless, in the Beirut refugee camps of that name.

Second update: 1984-2002

This encompassed the first, non-violent intifada, or uprising, staged by the inhabitants of the Israeli-occupied West Bank and Gaza, which Yitzhak Rabin, who will become the prime minister in 1992-1995, instructed his military to put down by “breaking their bones” - with medics in attendance to ensure that no “irreversible” damage was done in the breaking.

It also included Arafat’s very public, penitential pledge to “renounce terrorism”, which went unmatched by any reciprocal Israeli propensity, let alone pledge, to reduce its own, vastly disproportionate “defensive” violence.

In addition, this period encompassed the Oslo Accords, the diplomatic breakthrough that was supposed to lead, via an Israeli withdrawal from the occupied territories, to a final “two-state solution” of the conflict.

But it never would or could, as settlers turned to violence and terror, against other Israelis as well as Palestinians, to protest and thwart it - one of these being the assassin of Rabin, the “traitor” of Oslo, and another the American Israeli doctor, Baruch Goldstein, who machine-gunned to death 29 Muslim worshippers in Hebron’s Ibrahimi Mosque. Israelis’ reverence for him yielded nothing, in its nationwide breadth and intensity, to that which Palestinians habitually bestowed on their such terrorists and “martyrs”.

This period also saw the rise of Hamas, the Islamist rival to a now non-violent Fatah, and the first great wave of suicide bombings that became its gruesome speciality; and the outbreak of the second, violent intifada, which General Ariel Sharon, the incarnation of extreme Israeli violence, had sought deliberately to provoke so as to be able to smash it utterly - and in the process sabotage any prospect for the kind of peace that Oslo proffered.

Third update: 2003-2023

This one opened with a spectacular "first" in the history of Israel’s violence: that of getting others to administer it where it felt unequal to doing so itself. For such was the Iraq War.

No Israeli soldier took part in it. Yet it was very largely, even mainly, on Israel’s behalf, if not at its very behest, that in March 2003 the United States (and its British ally) invaded and occupied that ancient Arab land, in order to overthrow its existing regime and establish a whole new, supposedly US-friendly and possibly Israel-friendly order in its place.

It was perhaps the most extraordinary example yet of Washington’s historic, well-nigh slavish, support for Israel - support that Israelis themselves recognise as one of the two essential pillars of their country’s very existence, survival and still unfolding destiny in the hostile Middle East environment of its own making; the other, of course, being Israel’s very own, very strong right arm - the central theme of this book.

Whenever, for example, the Israeli army 'cuts the grass' in Gaza, it breeds revulsion around the world at what this grass mostly consists of

The war was a disaster, in varying degrees, for all its participants. But not for Israel, relishing as it did this shattering of so potentially powerful, and hostile, an Arab state. Nor was it for Iran, that other, and even more formidable, of its “faraway” enemies. And Israel now conspired, for years to come, to ensure that the US would go to war against Iran too, should it ever get close to the possession of nuclear weapons that would challenge its own, no less illicit and deviously acquired, large arsenal of them.

As for Israel’s other, “near” enemies, over the next 20 years, one of the world’s most powerful armies ran into quite a bit of trouble dealing with those. They consisted of a handful of non-state actors, notably the Palestinian group Hamas and Lebanon’s Iran-backed Hezbollah, which had taken up the “resistance” against the Zionist intruder that all Arab states, and even Arafat’s Fatah, had by now abandoned.

In addition to one quite “big” one, against Hezbollah in 2006, Israel waged an interminable series of supposedly “small” wars on Gaza, the Hamas stronghold. It called them “mowing the lawn” or “cutting the grass”, as if warfare were a routine chore that never ends - and as, indeed, it self-evidently cannot for a nation which, at least according to its longest-ever-serving prime minister, Netanyahu, “will forever live by the sword”.

Those that do so are - as the axiom has it - apt to die by it. The Israelis’ 11th-century forerunners, the Crusaders, certainly did. And the similarities between that epic venture of medieval Christendom and Zion’s of today are inescapable; not only in their essential natures, objectives and means of achieving them, but in the ways that their conflicts with the states and peoples of the region actually unfolded.

'Crusader anxiety'

Israelis in general indignantly reject the charge, standard throughout the Arab and Muslim world, that they are the Crusaders of our times. But they do so essentially on moral grounds only: their cause, the return of an exiled and persecuted people to their historic homeland, simply brooks no comparison with the imperial conquests of the medieval church militants.

For obvious reasons, however, they take a very special interest in them, and their country has become a significant centre of Crusader scholarship. What scholar David Ohana calls "Crusader anxiety", or the "hidden traumatic fear" that "the Zionist project" may “end in destruction” as complete as that of their Christian predecessors, has become an intrinsic part of the Israeli psyche - or, at least, of those who are at all aware of these critical historical parallels. And, he points out, the prospect of an Iranian nuclear bomb does nothing to allay such fears.

Not the least of these resemblances has been the primordial importance, for both Crusaders and Zionists, of those two key, above-mentioned factors: military prowess and the support of foreign powers.

For the one, throughout their 192-year presence in the Holy Land, the support came mainly in the shape of a seemingly inexhaustible supply of new Crusaders led by the kings, princes and great barons of feudal Europe. For the other, it has come mainly from the bounty - armaments galore, annual aid amounting to about one-third of what Washington hands out to the entire world, extravagantly partisan diplomacy - heaped on it by the American superpower.

It was a decline in the latter, rather than any loss of military prowess, that eventually did for the Crusaders.

It could be the same for the Israelis.

But ironically, and quite unlike the Crusaders, it is precisely the former - their violence - which, as much as anything else, will bring that decline about. For whenever, for example, the Israeli army “cuts the grass” in Gaza, it breeds revulsion around the world at what this grass mostly consists of - which is never Palestinian “terrorists”, but non-combatant men, women and, above all, children, buried beneath homes reduced to smithereens.

And that is only the most periodically shocking of things; a host of others increasingly call into question the integrity and the very legitimacy of the Jewish state.

Epilogue

“Not a hair of their heads shall be touched.”

Thus spoke Chaim Weizmann, the great statesman of early Zionism, in the aftermath of his diplomatic triumph, the Balfour Declaration, which he had conjured from the wartime government of Great Britain in November 1917. He had in mind the Arab inhabitants of Palestine, on whose territory the “national home for the Jewish people” was to arise without “prejudice” to these “non-Jewish communities”.

And he was “certain”, he later said, “that the world will judge the Jewish state by what it will do with the Arabs”.

But remarkably, in his address to the postwar Paris Peace Conference of 1919, he made no attempt to explain just how, precisely, this making of Palestine “as Jewish as England is English” - as he described the Zionist project - could possibly be achieved without harming a hair of anyone’s head.

A famous, and better qualified, attendee at the conference would not have been impressed if he had; Colonel T E Lawrence, otherwise known as Lawrence of Arabia, had already divined, upon meeting Weizmann in person, that what he was really after was “a completely Jewish Palestine” within 50 years - which, the Holocaust aiding, he was actually to get in just 30.

Inevitably, then, any objective history of Zionism could hardly be other than a history, too, of the very great harm which - following almost exactly in the Crusaders’ footsteps - was actually to come down, not just on the inhabitants of Palestine, but on other peoples and states of the region.

But as it did, and contrary to Weizmann’s expectations, the world didn’t “judge”, let alone chastise, Israel - or not, that is to say, those parts of it, essentially the US and the West, whose judgement mattered.

Original sin

Consider Israel’s first, most formative, fateful and egregiously Crusader-like of acts - its “original sin”, to which it owes its very existence.

In 1099, the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem arose upon the debris of one of “the greatest crimes of history”, the massacre of the entire Muslim and Jewish population of the holy city. Eight and a half centuries later, in 1947-48, Israel was born of a similarly massive “crime against humanity”; or, at least, had the article of international law pertaining to that offence been operational at the time, and had anyone had the will to invoke it, that is surely what the Palestinian Nakba, or catastrophe - the ethnic cleansing and expulsion, through force, terror and many an atrocity, of those “non-Jewish communities” - would have been judged to be.

Ben Gurion and his successors yearned for others to attack them. Meanwhile, all they could do was await opportunities to attack those others first

There was no such will, not on the part of western publics, still less of their governments. And least of all Washington’s. For it was in the US that pro-Jewish/Israeli sentiment ran highest, amid widespread celebration of the “noble dream” (as Abraham Lincoln once called it) come true.

There, too, politicians - and journalists and academics - risked the punitive, sometimes career-threatening wrath of an already redoubtable institution, the Israel lobby, if they strayed too far from this celebratory orthodoxy. One who did, and was all but crucified for it, was Dorothy Thompson, perhaps the most famous and admired American journalist of her day; she called the newborn state “a recipe for perpetual war”.

And so, Crusader-like, it was to prove. The chivalry of medieval Christendom spent 192 years doing more or less continuous battle with this or that kingdom or sultanate of an Arab-Muslim Middle East - then pretty much as internally fractious and fragmented as it is today - until, losing western support, they ended up being literally thrown into the sea.

The Israelis have been at it, in very like fashion, for a good 75 years now, in what their official military doctrine defines as “wars” and “campaigns between wars”.

Conquest and expansion

To begin with - for both the Crusaders and the Israelis - such wars were largely wars of further conquest and territorial expansion.

No sooner had Baldwin de Bouillon been crowned first king of Jerusalem, on Christmas Day 1100, than he set about enlarging his diminutive kingdom - and this eventually encompassed the whole of what is now Palestine, and bits of Syria, Jordan and Lebanon, as well. It surrounded itself with formidable frontier fortifications and agri-military settlements, adumbrations of Israel’s great border “walls” and its farm-and-fighting kibbutzim.

David Ben Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, was bent on expansion, too - to be accomplished, he once said, not by “moralising” or “sermons on the mount”, but by the “machine guns which we will need”.

But unlike his medieval predecessors, innocent of any such niceties as the rules and ethics of war, he couldn’t just invade and conquer a neighbouring country at will. His, after all, was a “peace-loving” nation, which had only just secured its very controversial admission to the United Nations on the strength of a solemn pledge to that effect.

Nor would such an action have been becoming of the supremely moral and democratic state, and “light unto the nations”, which he told the world he was building; and which much of that world, notably its liberals and its left, had already taken to its heart, on account, among other things, of its “inspiring” socialist ideals and the kibbutzim at the core of them.

Ben Gurion and his successors yearned for others to attack them. Meanwhile, all they could do was await - or seek to manufacture - opportunities to attack those others first; opportunities which, crucially, would enable them to do so in the guise of legitimate “self-defence”.

The perfect one finally arrived in June 1967, when, in response to taunts and provocations on its part, Arab armies began converging on Israel amid a foolish and fearsome clamour of bellicose rhetoric. For a moment, the world trembled on Israel’s behalf: was it to become the site of a second Holocaust within 25 years of the first?

No way, of course. As foreseen - and long prepared for - the iconic, one-eyed general, Moshe Dayan, and other disciples of the master, immediately saw to that. In the Six-Day War of June 1967, they achieved at a stroke the almost identical territorial and strategic goals that King Baldwin had taken 20 years to do eight centuries before - plus conquest of the whole of the Sinai. They also precipitated a mini-Nakba, another great wave of Palestinian refugees.

The world did not judge Israel for that either. On the contrary, it raised it, the “darling of the West”, to unprecedented heights of prestige and popularity.

Judging the Zionist enterprise

And with this - Crusader-like again - the Israelis found themselves presiding over an indigenous population, composed of those they had not killed or expelled, almost as numerous as their own.

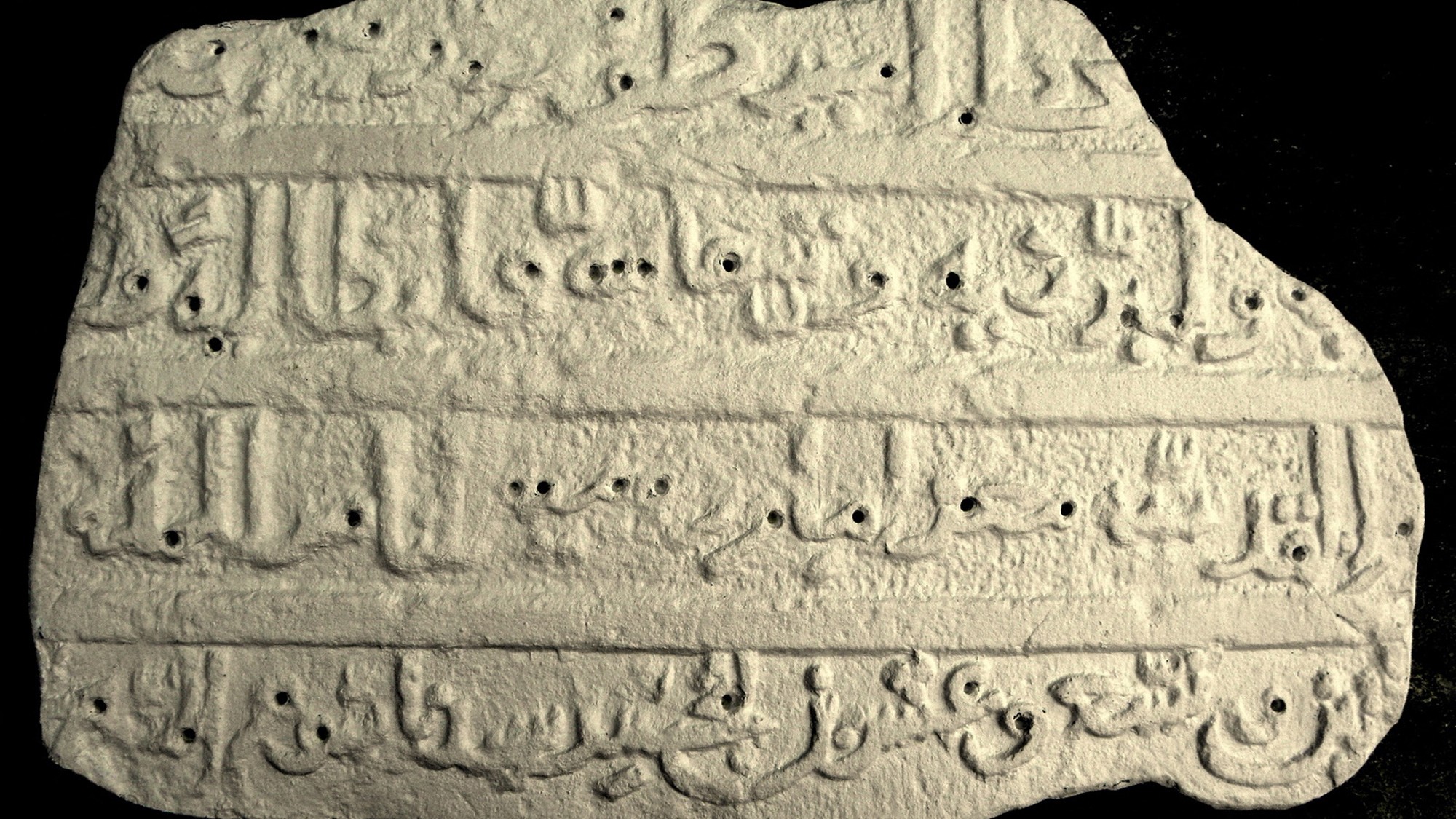

Crusader historians rarely fail to cite the 12th-century Muslim traveller Ibn Jubayr, and his description of a Muslim community that “bewails the injustice of a landlord of its own faith, and applauds the conduct of its opponent and enemy, the Frankish landlord, and is accustomed to justice from him”.

For his is perhaps the most credible surviving eyewitness evidence that, however barbarous in battle, the Crusaders were perhaps not all that bad in governance - or not, at least, in relation to the admittedly far from exacting mores of the time.

This was eventually to imperil Israel in the same way that a similar process across medieval Christendom had once imperilled the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem

Could the same, or better, have been said of the Israelis about their present-day conquest and occupation of the West Bank and Gaza? Objectively speaking, it couldn’t - and yet it generally was. For theirs, the Israelis maintained, was “the most benevolent occupation in history”, and a still doting world was little disposed to question it.

So when did it come to pass, that which could aptly be described as the world’s first - and truly damning - “judgement” on the Zionist enterprise it had for so long, and uncritically, embraced? For come, as Weizmann had predicted, it eventually did - albeit several decades after he had.

It came, aptly enough, in the context of the conflict’s most characteristic, Crusader-like of features: its perpetual violence.

Peddling its violence versus the Palestinians’ as tantamount to good versus absolute evil had long brought Israel a certain additional credit in the eyes of a western public already so smitten in its favour.

Palestinian “terrorists” were simply "murderous fanatics bent on killing Jews"; Israel’s army - which subsequently took to calling itself the “most moral in the world” - surpassed all others in its concern for innocent civilian lives.

But during its 1982 invasion of Lebanon, it tore that already frayed contention irretrievably to shreds. When Sharon as defence minister unleashed that country’s Christian militia, the Phalange, on the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila, he not only knew full well what it was going to do there, but he also spurned the entreaties of American diplomats, who obviously knew too, to stop it until the genocidal job was done.

Western disenchantment

Virtually the whole world reacted with varying degrees of shock, or with the tearful sorrow of one 80-year-old Israeli professor, who had instantly discerned in it a carbon copy of Babi Yar, the ghetto into which “the Nazis sent the Ukrainians to massacre the Jews”. Nowhere, said the Washington correspondent of the Jerusalem Post, had Israel done greater damage to itself than in the US, its friend, ally and benefactor extraordinaire.

Although, unlike the Crusades, Zionism was autogenous in origin, it was essentially the great powers of the day, first Britain and then the US, which enabled its implantation on others’ land

Sabra and Shatila, and the whole military misadventure in Lebanon - Israel’s Vietnam, of which it was the gruesome climax - was the first big signpost pointing towards what was to become the long, slow process of western disenchantment with its “beautiful Israel” of yesteryear.

And this was eventually to imperil Israel in the same way that a similar process across medieval Christendom had once imperilled - and finally undone - the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem.

The papacy, the nearest thing to the superpower of its day, had first preached holy war for the liberation of the Holy Land from infidel Muslim rule, and then, over nearly two centuries, sponsored or otherwise inspired campaign upon campaign to that end.

Although, unlike the Crusades, Zionism was autogenous in origin, it was essentially the great powers of the day, first Britain and then the US, which enabled its implantation on others’ land, along with its subsequent growth, maturity and continuing survival in the hostile environment of its - and their - making.

It was not for moral reasons, wrath or remorse over the very un-Christ-like conduct of its “soldiers of Christ” that the papacy finally wearied of the whole messianic enterprise. It appears to have been little troubled, if at all, by their great, inaugural atrocity, the Jerusalem genocide - or by later, lesser ones, such as Richard the Lionheart’s mass execution of some 2,700 Muslim prisoners of war. It was simply turning its attention to new and more pressing preoccupations closer to home.

The 20th-century world, with its 20th-century “values”, could hardly, in all honesty, but have been troubled by the similar - if perhaps not quite so nasty - things that the Crusaders’ 20th-century successors have done, and continue to do, in pursuit of their very similar dream.

Respect, devotion, solicitude - these, genuine or assumed, Israel still commanded in many quarters, particularly governmental and official ones. But in many others, and in society at large, such sentiments were steadily yielding to their opposites: to criticism, censure or outright condemnation, and calls for punitive action, like the sanctions, arms embargo and economic boycott that brought down the apartheid regime in South Africa.

Living by the sword

The Israelis lumped all this under the heading of “delegitimisation”. And, for them, delegitimisation ultimately amounted to an existential threat - a no less serious one, according to Netanyahu, than a nuclear-armed Iran or the missiles of Hamas and Hezbollah.

Why? Because if Israel was a state forever condemned to live by the sword, as Netanyahu said it was, then it could not fashion, maintain and effectively wield that sword without the support and goodwill of Washington and the West, any more than the Crusaders could have done without that of the papacy and medieval Christendom.

Thus, the US was obliged, by law, to keep it continually supplied with every possible “superior military means” to “defeat any … military threat from any individual state or possible coalition of states”.

Every time such things happened, and the world got to hear about them, the 'Jewish and democratic state' delegitimised itself a little fraction more

The arms themselves were only one thing; another was the uses to which Israel put them, and which, however unlawful in intent or criminal in execution, the US could always be relied upon to support or condone.

Thus automatically, robotically, did it cast its veto against any resolution, of which there were dozens down the years, even mildly critical of Israel at the UN - the very body to which, virtually unique among nations, it effectively owed its very creation - and with it, of course, the “legitimacy” that, it now lamented, the world was seeking to deprive it of.

It would undoubtedly go on doing so, with ever-growing intensity. For every time the “most moral army in the world” buried women and children - along, sometimes, with an actual “terrorist” or two - beneath homes in Gaza; every time a leading politician or rabbi delivered some breathtakingly racist or bloodcurdling remark about Arabs or Palestinians; every time religious settlers embarked on a “pogrom”, an olive tree-uprooting campaign, or an attempt to burn down an entire Arab town, praying as they went about it, the pressure increased.

Indeed, every time some religious or ultra-nationalist firebrand ascended al-Haram al-Sharif, the Noble Sanctuary, site of Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock, and dropped an incendiary hint or two about resurrecting an ancient Jewish temple in their place - every time such things happened, and the world got to hear about them, the “Jewish and democratic state” delegitimised itself a little fraction more.

Clearly, its more forthright friends began warning it, the one-time “darling of the West” risked becoming its “pariah”, along with the likes of its arch-enemy, the Islamic Republic of Iran.

'Shared values'

With notable exceptions, that was how matters stood with much of the western public in the early 2020s. This was worrisome, but more so was the prospect that western governments, being democratic ones, would surely, sooner or later, heed their publics, and act to propitiate them.

There were as yet, it is true, not too many premonitory signs of that, and virtually none at all from the all-important American one. Indeed, not merely uninfluenced by the “delegitimisation”, successive administrations actually joined Israel in its fight against it.

As recently as July 2022, and from Jerusalem itself, US President Joe Biden was solemnly pledging to “combat all efforts to … delegitimise Israel”, given the two countries’ “shared values” and their “unwavering commitment to democracy”.

That Israel could be called a democracy at all was debatable. A true democracy would normally encompass all the inhabitants of the territory that a state comprised, or - as in this case - laid claim to.

But in no way did Israel’s “democracy” extend to that vast majority of Palestinians, inhabitants of the occupied territories, over which it had ruled for more than half a century, while discriminating against the minority of them who were inhabitants of Israel proper.

Imagine, then, what must, or surely should have, been the embarrassment and consternation in Washington, when, just months after Biden’s Jerusalem proclamation, Netanyahu embarked on a programme of “judicial reforms” that would further undermine that already doubtful democracy, or destroy it altogether.

True, these supposedly “shared values” weren’t the real, or at least the main, reason for Washington’s boundless indulgence of its “favourite nation”. That - as Ilhan Omar, the iconoclastic young Muslim and Somali-born congresswoman from Minnesota, so succinctly put it - was “the Benjamins, baby”.

Omar was referring to the $100 banknote, which sports an image of Benjamin Franklin, one of the US “founding fathers” - dollars being the principal “currency”, both literally and figuratively speaking, lavished by the lobby and its super-rich friends on the suborning of Washington’s great and good on Israel’s behalf.

Whatever the reason, it made little difference. The extraordinary thing was that, in this, his democracy-demolishing fit, an Israeli prime minister was effectively stripping an American president of just about his last remaining, ostensibly principled justification for his country’s historic but - as Arabs and Palestinians not unreasonably see it - manifestly unprincipled, politically expedient bias in Israel’s favour.

And, in any case, whether Israel was still a democracy of sorts or not, that now counted for little against what, in other ways, it also was, or on the way to becoming.

'Warriors of God'

It was an ethnocracy, long embarked on a form of apartheid that - as visitors from South Africa, such as the late Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the anti-apartheid champion, who called the “parallels to my own beloved South Africa … painfully stark indeed”, always testified - was as bad, if not worse than what used to be their own.

It was gradually taking on the attributes of a theocracy, with rabbis, often of the most bigoted and reactionary kind, gaining such influence in the nation’s affairs that, in the eyes of anxious secularists, who now habitually refer to this process as the “Iranisation” of Israel, it was beginning to look like a Jewish version of the ayatollahs’ realm.

It was a state and a society held hostage by a golem of its own creation, its religious settlers - wild and weird embodiments of a fusion between the 19th-century “blood-and-soil” nationalism in which their secular predecessors were steeped, and the newfangled, militant Judaic messianism of their own, whom it would probably require a civil war to rein in.

The state really was looking more and more like the Crusaders themselves, taking after them not merely in method - perpetual war - but in aspirations too

And, yes, in its deepening religiosity, the state really was looking more and more like the Crusaders themselves, taking after them not merely in method - perpetual war - but in aspirations too, with one in particular that exemplified the resemblance above all others.

For those antique "warriors of God”, the supreme, most sacrosanct of tasks had been to save the Holy Sepulchre - the site, Christians believe, of Jesus’s crucifixion, burial and resurrection - from the “pollution” and derelictions of Islam.

Similarly, for an unknown, but growing number of their Israeli successors - and not just religious ones - the return to Zion will not be complete until the Third Temple arises, alongside Al-Aqsa and the Dome of the Rock, or in their stead, on this, the third-most holy place of Islam; similarly indeed - but, of course, if that ever actually came to pass, apocalyptically, too.

So will the world, upon finally waking up to all that their protege has wrought upon the land and peoples of the region in the three-quarters of a century since Weizmann forecast that it would “judge” Israel for this - will it forsake or repudiate the state, leaving it to whatever fate might expose it?

By the light of modern "values", the US and the West would have much stronger grounds for doing so than the papacy and medieval Christendom once had for abandoning the Crusaders by the light of theirs.

Improbable, no doubt. But the more Israel "delegitimises" itself in the eyes of the world - and it is making one helluva of job of that in Gaza right now - the less improbable it becomes, and with it the possibility, and nightmare scenario of Ohana, the Crusaders scholar, that its fate will come to resemble that of the Crusaders themselves. Not driven into the sea, of course, but in some way or another strategically/militarily/diplomatically overcome.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.