ANALYSIS: Palestine ICC entry a diplomatic milestone

From 1 April, Palestine will be a party to the ICC’s treaty, the Rome Statute

Membership in the ICC is part of a process that can lead to war crimes probes of Israelis and Palestinians and shake up a stalled peace process (AFP)

Published date: 26 June 2015 01:59 BST

|

Last update: 9 years 5 months ago

NEW YORK – Palestine is only days away from gaining full membership to the International Criminal Court (ICC) – part of its diplomatic bid to secure justice for victims, win more international clout and improve its negotiating position with Israel.

From 1 April, Palestine will be a party to the ICC’s treaty, the Rome Statute. While this only grants Palestinians a few extra privileges, it is part of a process that can lead to war crimes probes of Israelis and Palestinians and shake up a stalled peace process.

“It gives the Palestinian government rights … including the issues of elections, of judges and prosecutor, and votes on the amendments of the Rome Statute, as well as the possibility to refer situations to the ICC prosecutor,” ICC spokesman Fadi El Abdallah told Middle East Eye.

Dispirited by slow progress towards a peace deal with Israel, Palestinians have sought to “internationalise” their struggle by securing UN recognition in 2012 and by joining the ICC, a 123-member war crimes tribunal based in The Hague.

ICC membership throws up several tough questions, such as what “crimes” can be investigated, whether the court will face political pressure and whether ICC-style justice will change anything on the ground between Israelis and Palestinians.

ICC Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda can probe crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes in Gaza, East Jerusalem and the West Bank since June 2014 – a jurisdiction that was backdated to before Israel’s attack on Gaza last July and August.

She can probe suspects from anywhere, including Israel, which – like the US, Russia, China and other key powers – is not an ICC member. A “preliminary examination” is already probing Israel’s 50-day Gaza assault, West Bank settlements, Palestinian rocket attacks and other potential crimes, she said.

This early-stage process could take years, and must overcome legal hurdles before anybody – whether Israeli or Palestinian – faces charges. First, the crimes must be deemed serious, and the ICC can only act when national courts are “unable or unwilling” to do so, according to court rules.

Investigators are expected to focus on the high civilian death toll during the 2014 Gaza conflict. Tens of thousands of homes were destroyed and over 2,100 Palestinians, mostly civilians, died, including about 500 children. On the Israeli side, 67 soldiers and six civilians were killed.

Shawan Jabbarin, from the International Federation for Human Rights, a pressure group, said that Israeli bombs indiscriminately hitting Palestinian homes was clearly criminal. “It’s now time for ICC to move from a mere preliminary examination of the conflict to a full investigation,” he said.

Israelis have already staked out a defence for this, saying they try to minimise civilian deaths by warning Palestinian residents about impending attacks. They say Hamas uses Palestinian civilians as human shields and fires rockets from schools and hospitals.

Israeli settlement building in the West Bank is also expected to feature in ICC probes, because the Rome Statute defines the “transfer, directly or indirectly, by the occupying power of parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies” as a war crime.

Hamas, the militant and political group that runs Gaza, is also likely to come under scrutiny. It routinely fires rockets at southern Israeli towns; and the ICC treaty defines “intentionally directing attacks against the civilian population” as a war crime.

Kenneth Roth, Executive Director for Human Rights Watch, another pressure group, said Hamas “is extremely susceptible to prosecution”. “Those are almost the easiest cases to make: indiscriminate rocket attacks onto Israeli-populated areas,” he told MEE.

According to George Bisharat, a Palestinian-American law scholar at California University, atrocities by Israeli forces are more systematic and widespread, but ICC prosecutors will likely investigate both sides for the sake of appearing even-handed.

“Israel knows very well it has engaged in serious violations of international law for decades and knows it is vulnerable – that’s why they’re alarmed,” he told MEE. “But the ICC cuts both ways; it is virtually inconceivable that investigations will not occur against both sides.”

Prosecutor Bensouda said she was insulated from political pressure and follows only ICC rules and evidence: “We execute our mandate in strict conformity with the law and in complete independence and impartiality,” she told MEE.

While Bensouda is credited with streamlining the ICC, the court still struggles to prove its legitimacy and imprison rogues. Last year, prosecutors dropped charges against Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta, while Sudan’s president Omar al-Bashir has dodged an ICC indictment since 2009.

David Hoile, a public affairs consultant specialising in African affairs and a longtime critic of the ICC said the court is costly, biased and hires untrained, callow judges from the court’s donor states. It is a “hopelessly inept as a legal institution” and “irreparably unfit for purpose”, Hoile told MEE.

As such, the ICC has already been attacked by both sides in the incendiary Israeli-Palestinian struggle. Palestinians say it will doubtless succumb to pressure from Israel’s ally, the US. Israelis say it is has already pre-judged the outcomes.

While the court offers a new venue for the Israel-Palestine conflict, the two sides have fought legal battles before.

In February, a New York jury awarded $218.5 million in damages against the Palestinian leadership for allegedly backing attacks in Israel that killed or wounded US citizens a decade ago. Last year, pro-Israel lawyers convinced another New York jury that Jordan’s Arab Bank had materially supported Hamas.

Previous efforts to prosecute Avi Dichter, Israel’s former security chief, over Palestinian civilian deaths in 2002, failed in the US. Attempts to issue arrest warrants against Israeli officials, such as Ariel Sharon and Tzipi Livni, via European courts, did not succeed.

But rulings do not always back Israel. Palestinian lawyers won a landmark victory in 2004, when judges at the UN International Court of Justice (ICJ) voted 14-1 against Israel’s wall-construction on occupied Palestinian land and called for building work to stop.

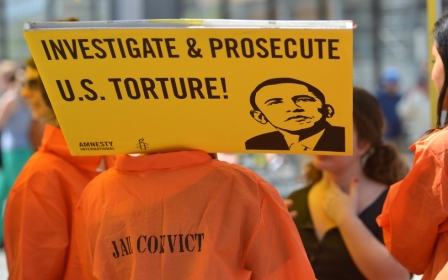

“As with the ICJ ruling on the wall, the evidence of laws of war violations that will be presented to the ICC is so substantial that, for it to retain any legitimacy, it must investigate and prosecute atrocities against Palestinians,” Michael Ratner, director of the Centre for Constitutional Rights, told MEE.

As ICC judicial cogs slip into gear, Israel and the US both assert that Palestinian membership of the court, as well as UN bodies, does not alter the reality that they need to negotiate a peace deal via direct talks with Israelis.

Talks stalled 2014 and, this month, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu rejected the two-state solution that had been the basis for deal-making. US President Barack Obama’s growing hostility to Netanyahu may suggest that he is more accommodating of Palestinian efforts at the ICC.

Some experts argue that Palestine’s looming ICC membership has already affected behaviour in the region. Fearful of war crimes probes, Hamas is unleashing fewer rockets while Israel is building fewer settlements, said Roth.

“Both these parties, especially the Palestinians, are fastened on international legitimacy,” said Beth Simmons, a Harvard University law scholar. “It strikes me that this … ought to provide the strongest circumstances under which deterrence is likely to operate.”

According to Bensouda, the court not only deters atrocities – it protects weaker states from cross-border bullies. With only Jordan and Tunisia in the ICC, the Middle East has fewer members than any other region, she told MEE.

“Once we have territorial jurisdiction with respect to a state party to the Rome Statute, those most responsible or notorious for committing mass crimes on the territory of that state, whether they are nationals of a state party or otherwise, can be investigated and prosecuted by the ICC,” she said.

“It’s a form of protection for countries from the Middle East and elsewhere to become part of the Rome Statute system.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.