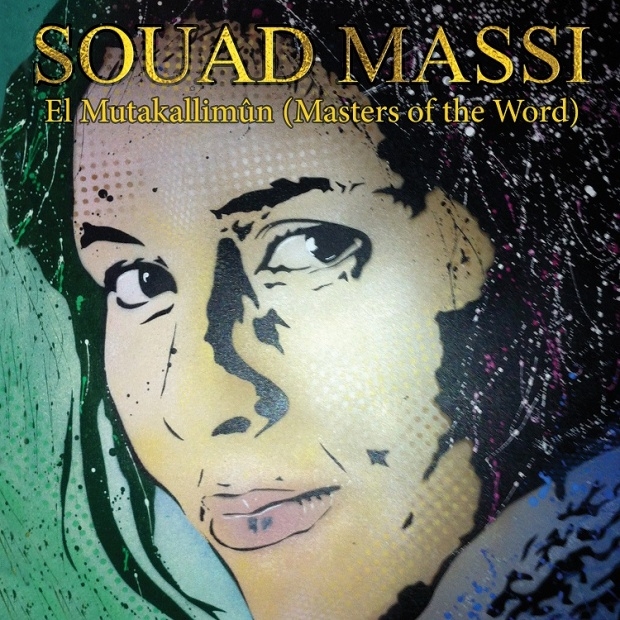

INTERVIEW: Souad Massi, 'I do believe in the power of the words'

In her new album, El-mutakallimun, Souad Massi follows in the footsteps of the legendary poets of the Arab-Muslim Andalusia. The artist, through 10 beautiful texts illuminated by original compositions, brings into sharp focus the work of those poets who illustrate an era when expression was rebellious and diverse.

MEE: Why did you dedicate this album to the Arab-Andalusian poets of Spain?

Souad Massi: I just wanted to give people the opportunity to discover the beauty of the Arab culture. We are not barbarians or uncivilized people. The Arab-Muslim world has produced great works in science, philosophy, mathematics, medicine and poetry, but it all seems forgotten now. I am of Berber origin, but I also belong to this heritage. I was raised in an Arab culture which I cherish. I grew up in a house where we listened to the Arab-Andalusian music, Chaabi and Berber music. Sometimes, I am tired of being confused with people who have nothing to do with the Arab culture. I notice that some young people who study mathematics and algorithms have no idea that Arab scholars have developed these sciences, or that Ibn Sina’s [Avicenna], Qanun [Canon] revolutionised medicine, as much as Arabic astronomy has developed instruments that were later used to map the world and to discover other lands. Why do we not speak of this more often?

MEE: How do you explain this?

Souad Massi: I sometimes have the impression that Europe does not want to draw attention to this cultural richness and these scientists. It is also up to us to ensure that our children, especially when we do not live in our own country, learn their history and that of their homeland. Arab youth sometimes faces an identity crisis; and in France, where I live, they sometimes have to choose between rejection of their own culture or a rather skewed version of their religion. I feel I want to send a message to them and say: “Look at your ancestors. Did you know that Ibn Firnas, who came from Muslim Andalusia, was the first man to fly? Read Ibn Rushd [Averroes] without whom Europe would not have rediscovered Aristotle or the Greek philosophers, thus could not went through the Renaissance era”

MEE: The album’s title, El-mutakallimun, refers to “the speech masters.” Do you believe in the power of poetry?

Souad Massi: Yes absolutely, I do believe in the power of words. The great politicians, those who really made a difference, were primarily great speakers. I am very interested in Malcolm X and Martin Luther King’s journeys, and I was amazed by their ability to motivate the crowds. In my opinion, the mutakallimun [the kalamistes, from kalam: the book] did also believe in it. In Arab-Muslim Andalusia, they used to give original public lessons where they attempted to reconcile reason and faith. Above all, they were celebrating human freedom. El-mutakallimun literally means “scholars who master the expression.” The kings used to surround themselves with these scholar poets because people cherished them.

Even today, men in power like to surround themselves with artists in order to get some of their lustre. I like these words written by a contemporary Iraqi poet Ahmad Matar: “Poetry is not an Arab regime that eclipses with its leader’s death. And it is not an alternative to action. It is an art form whose mission is to disrupt, expose, stand witness to the reality and that expands beyond the present time. Poetry comes before the action... So poetry is regenerating. Poetry illuminates the path and guides our actions.”

MEE: Texts such as “Houria” celebrate freedom, freedom of thought and resistance to power. Did you think of Arab Spring by selecting the texts?

Souad Massi: When you look at the history of the Arab world, it is made of authoritarian powers, but also of resistance. And this fact is still relevant today. In my opinion, it is also important to underline the fact that texts from the 9th century already denounced tyranny and described how poets resisted tyranny. Author of the poem “To the tyrants of the world” (Ela Toghat al-Alam), Tunisian poet Abou el Kacem Chebbi’s verses were taken up by protesters in Tunisia and Egypt.

They all chanted: “Beware! That neither the spring will deceive you. Nor the sky’s clarity, nor the light of day.” The Arab world is diverse and it existed before Islam’s era. These poems openly dealt with themes such as alcohol, sexuality and homosexuality; poets celebrated love, and even died of love as in the poem of Ibn Qays Moullawah, “O Layla” which was, in the entire Muslim East and India, the equivalent of Tristan and Isolde or Romeo and Juliet. I like to take refuge in these poems because the times we are living now sadden me. The Arab world seems to be delivered to chaos and war, and Europe to racism.

MEE: How do you explain the fact that your country, Algeria, is at a kind of blind spot while these movements are taking place in the Arab world?

Souad Massi: At the beginning of these movements, I have to admit, I was really happy. I said to myself: “Finally a breath of freedom!” The people will come forward to change things and overthrow all these dinosaurs. But in hindsight, I was more doubtful. I had the impression that some movements were not as spontaneous as they seemed to be, or that they were subsequently used for other purposes, it does sadden me.

For me, Europe has a share of responsibility for what is happening in the Arab world. When France sells Rafale fighter jets to Egypt ruled by Sisi, there seems to be a problem. Relating to Algeria, we had our own revolution in the 80s with the Berber Spring in 1988 and the civil war that followed in the 90s. Algerians then realised that this hasn’t brought them any changes. The trauma is still widespread in Algerian society. But to me, it would be preferable to act otherwise, peacefully, ideally. Because even though I am sad for those who died for their freedom, I think repression was very hard, especially in Egypt.

MEE: You played in Eyes of a Thief, a movie directed by Palestinian director Najwa Najjar. How was this new experience for you?

Souad Massi: Najwa Najjar is a friend, but she is a real fighter first. We shot in Nablus under the Israeli occupation and in very difficult conditions. It was painful to undergo, all these curfews, these ill people who could not pass the checkpoints, all these “herded” people. I know that this word could be shocking, but this is the reality I have observed. For a month, I lived in Nablus amid daily shootings, and yet people keep on working and above all living. Making this movie was a way for me to stand by the Palestinian people, and this wasn’t for the sake of vanity. For ten years I had received offers to do movies, and I turned them down.

It was a great - albeit difficult - experience because I had to play a character, and on stage I do not play, I am myself. But humanly, Palestinians have shown me their strength and their generosity. Nablus’s young girls have a free mind, they go to school, they are beautiful, they invited me to go out at night, whereas even in Algiers I do not go out after a certain hour. Any act of daily life is for them a form of resistance. I remember an old woman, dressed all in white, walking down the street with the portrait of her dead son. She invited me to drink tea and told me about her life and her son.

MEE: You said you refused to play in Israel? Why?

Souad Massi: If I had to go on tour in the Middle East and I was asked to perform in Israel, I simply could not. Yet I know that I have fans in Israel who send me beautiful messages asking me to perform in their country, but I really cannot.

An artist must also play this role to unite people but also to raise awareness. At the same time, this does not mean I hate the Israeli people, it simply means that I do not agree with their government’s policy. So, for the time being, not performing in Israel is the only way I have found to express that. Even though I can feel close to Jewish culture, I differentiate it from Israeli policy.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.