Lebanon pager attack: Did Israel break international law?

Lebanon has been rocked this week by an Israeli attack targeting Hezbollah that turned communication devices into bombs, leaving dozens dead and injuring thousands more.

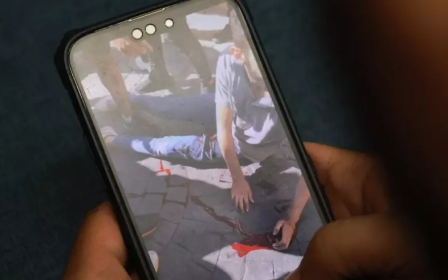

On Tuesday afternoon, thousands of pagers exploded across the country, killing at least 14 people.

On Wednesday, walkie-talkies blew up, including at the funerals of some of those who died the previous day: at the time of writing at least 20 people are dead from that attack.

Many of the estimated 4,000 people who have been maimed have injuries to the head and stomach. Some have lost their eyesight or limbs, notably fingers. Hundreds are still in a critical condition.

As is its policy, Israel has neither confirmed nor denied its alleged involvement in the attacks.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

But multiple media organisations, including within Israel, have reported that the Mossad secret service infiltrated Hezbollah supply chains and planted explosives in the devices.

Here Middle East Eye takes a look at the international legal implications of the attack.

What principles determine humanitarian law for armed conflict?

International humanitarian law is derived from international conventions, treaties, regulations and legal rulings. It includes the Hague Conventions, the Geneva Conventions and judgements by the International Court of Justice among others.

Part of its role is to impose limits on the suffering caused by armed conflict. From this have emerged several core principles that must be considered by states and other participants in conflict before they take military action.

"Distinction" stipulates that parties in warfare must at all times distinguish between combatants and civilian populations, as well as between military objectives and civilian objects (such as a house or a place of worship). Indiscriminate attacks, which hit civilians and civilian facilities as well as achieve military objectives, are prohibited.

"Proportionality" prohibits attacks that are expected to cause civilian deaths and injury, or damage to civilian objects, in a way that would be “excessive” in relation to the anticipated military advantage.

"Military necessity" permits measures that are necessary to accomplish a legitimate military purpose, namely, to weaken the military capacity of other parties in a conflict.

Has Israel's pager attack met these principles?

Alonso Gurmendi-Dunkelberg, a researcher at the London School of Economics focused on the international regulation of war, said it would be difficult for Israel to have checked the principles of proportionality, distinction and military necessity before the attack.

“We don’t have enough information to know how exactly the pagers were detonated, but if, as it seems from existing reports, they were simply simultaneously detonated, then it is difficult to see how these checks could have been undertaken,” he told MEE.

He said that to meet its obligations, Israel would need to have checked each individual communications device to make sure its detonation targeted a combatant - and not a civilian mistakenly holding the object or standing too close.

But it did not appear that any such individual checks were made, given that thousands of pagers and the walkie-talkies detonated simultaneously on each day.

Janina Dill, co-director of the Oxford Institute for Ethics, Law and Armed Conflict, said the attacks raised serious questions regarding proportionality.

She told MEE: “The question arises whether such a proportionality calculation for each explosion would even have been possible or meaningful given that we are talking about hundreds of explosions triggered at the same time.

“People typically carry their pages with them, including taking them home. It is hard to imagine that it would have been possible for the attacking party to limit the effects of these attacks in accordance with the demands of international law.”

Ellen Nohle, at the Diakonia International Humanitarian Law Centre, said that every single explosion had to comply with the aforementioned principles.

“It is possible that some of the attacks may have been lawful, while others were not,” she told MEE.

“It would be concerning if there was no observation to ensure that civilians did not have the pagers on them when they were detonated. A party is required to cancel or suspend an attack if it becomes apparent that the target is not a military objective or combatant.”

Civilians were among those killed and wounded during the attacks. Two children were killed, including Fatima Abdullah, the nine-year-old daughter of a Hezbollah member. Four health workers from private hospitals in Beirut’s southern suburbs were also among those killed.

What is a 'legitimate target'?

Multiple media reports state that the vast majority of those targeted by Israel’s attacks were not engaged in any form of combat at the time.

Many were going about their daily lives: pagers and hand-held radios exploded in homes, supermarkets, vehicles, and even at a funeral.

Gurmendi-Dunkelberg said that it is possible under international law for anyone with a continuous combat function in Hezbollah to be targeted, irrespective of where they are.

“Combatants [including soldiers] can be targeted when doing groceries, provided that distinction and proportionality are respected."

However, added Nohle, under the principle of military necessity, no more force than is “absolutely necessary” to achieve the objective can be applied.

So were all those targeted combatants?

No, they were not. The dead included non-combatants, such as Muhammad Hassan Nour Al-Din, an employee at Al-Rasoul Al-Aazam Hospital.

Among the wounded was Mojtaba Amani, the Iranian ambassador to Lebanon. MEE also understands that an employee of Al Mayadeen, a Hezbollah-aligned TV channel, owned a pager which exploded on his desk.

Nohle said: “It is not lawful to target persons merely affiliated with an armed group, who do not have a continuous combat function."

Dill added: “Only the members of the organised armed group that is part of Hezbollah are legitimate targets of attack in virtue of their affiliation to Hezbollah.

“All other individuals, including doctors and journalists with affiliation to Hezbollah, are immune from direct attack unless they directly participate in hostilities and then only while they are engaged in hostilities.”

But Gurmendi-Dunkelberg noted that there is scholarly disagreement over whether someone with affiliation to a group, but who is a non-combatant, can be targeted under international law.

"Israelis and US scholars say ‘yes’, but the ICRC says no,” he said, referring to the International Committee of the Red Cross.

"According to the ICRC, which is the view I subscribe to, to be targetable, you need to be more than just affiliated to a group, you need to have a ‘continuous combat function’ in said group."

Is it legal to use booby-trapped devices?

The common assumption is that Israel planted explosives in the devices, although it has made no comment on the attacks. Media reports have said the booby traps were created to cripple Hezbollah in any all-out war with Israel.

In November 2020, Iranian nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh was shot dead by a remote-controlled machine gun. Israel, which has tried for decades to stop Tehran's nuclear programme, was blamed for the assassination. And in January 1996, Yahya Ayyash, the chief bomb-maker for Hamas, was killed by a booby-trapped mobile phone in Beit Lahia, Gaza.

There are specific treaties and conventions around the use of booby traps in hostilities.

Under Amended Protocol II to the Convention on Conventional Weapons, to which Israel is a party, it is prohibited to use booby traps or “other devices” that are specifically constructed to contain explosive devices, according to Andrew Clapham from the Geneva Graduate Institute and author of the book War.

A booby trap is defined in the convention as a device or material that is designed, constructed or adapted to kill or injure, and which “functions unexpectedly” when a person disturbs or approaches an apparently harmless object.

“Other devices” describes munitions and devices designed to kill, injure or damage that are “actuated manually, by remote control or automatically after a lapse of time”.

Nohle said this week's detonations were likely to be considered under international law to be “other devices”.

Clapham told MEE: “It seems clear that the pagers [and walkie-talkies] have been adapted to kill or injure, and they function unexpectedly when performing an apparently safe act.

"Therefore their use is a violation of international law if carried out by agents whose acts are attributable to the state of Israel, or if carried out by individuals whose operations are directed by Israel.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.