Google backed Israel’s military. Now its workers are in revolt

It's early morning, and Zelda Montes walks briskly through the crisp New York air as they head to Google's headquarters on Manhattan’s 9th Avenue.

Montes, who self-identifies as they, fumbles with their ID card at the entrance, blending in with the steady stream of Googlers swiping through the security barriers as if it were just another day at the office.

Armed with an oversized tote bag, Montes pulls back their purple hair and heads to the 13th-floor canteen to order their usual: a dirty chai and an egg, avocado, and cheese sandwich with a bowl of raspberries. Their hands tremble slightly as they grip the coffee cup.

Locking eyes with two others, they get the signal that the coast is clear, head down to the entrance, and sit.

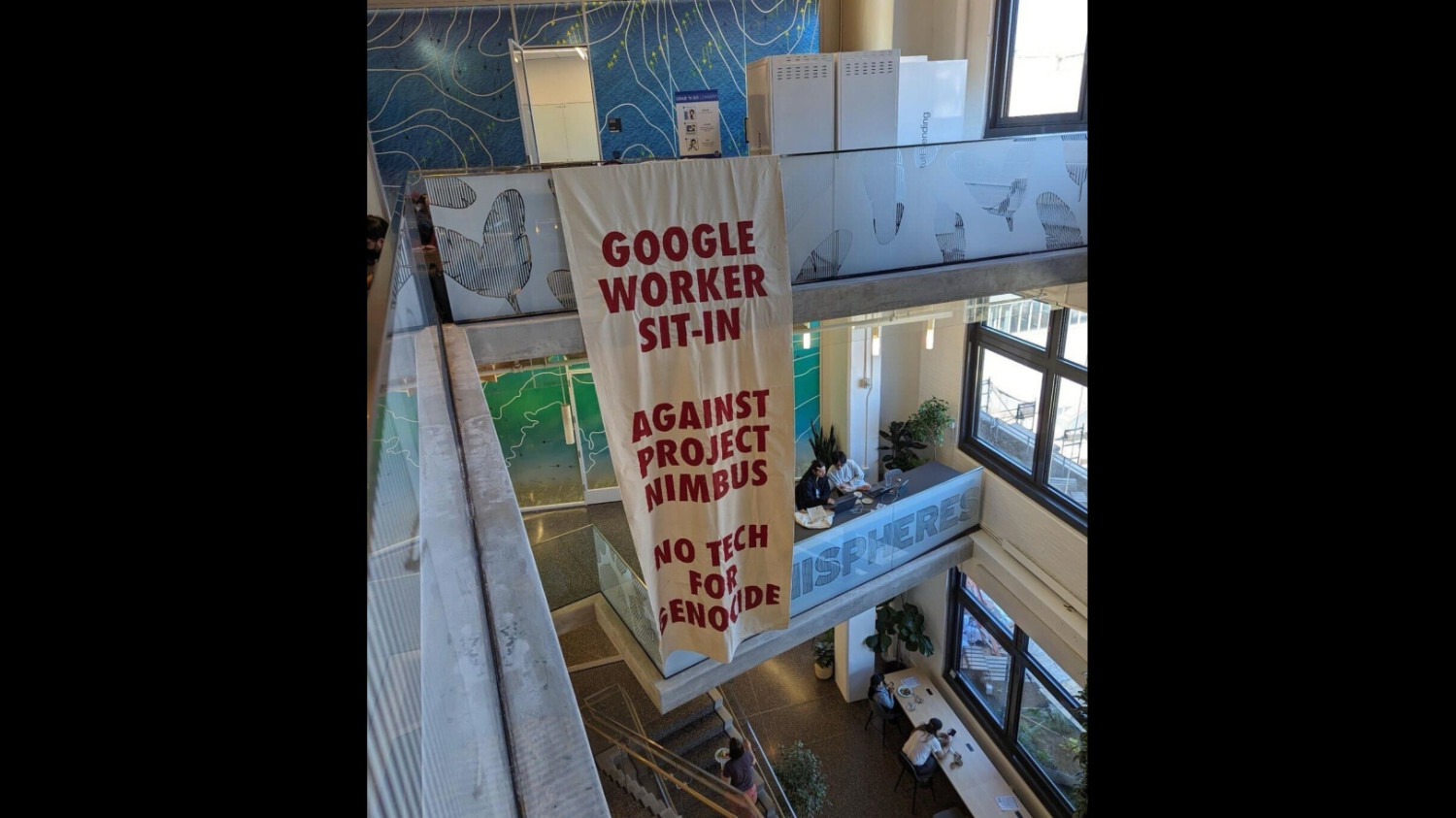

The three Googlers unfurl their banners and begin chanting to demand that Google do one thing: Drop Project Nimbus.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

But this will be the last time they sit inside Google's New York office as Googlers, as Google itself refers to its own employees.

"Getting fired felt like a possibility but never a reality," remarked Montes, one of 50 employees fired by Google for staging a 10-hour sit-in at one of its American offices in April.

For the last three years, Montes has been one of several activists calling for Google to drop Project Nimbus, a partnership Google and Amazon have with the Israeli government reportedly worth $1.2bn.

The partnership, which focuses on cloud computing, provides services to various branches of the Israeli government, including the defence ministry and the army.

Google, which has not responded to questions sent by MEE prior to publication of this article, has insisted in previous statements that Nimbus "is not directed at highly sensitive, classified, or military workloads relevant to weapons or intelligence services".

Working secretly, some Googlers - past and present from around the world - have been actively trying to organise workers to pressure the company to drop Nimbus and reveal the extent of its involvement with the Israeli army.

And since Israel began its war on Gaza, following the 7 October Hamas-led attacks in southern Israel, which have killed more than 41,000 Palestinians in the besieged enclave, calls to drop Nimbus have intensified. Some employees have staged physical and virtual protests against the deal over fears that Google is enabling Israel to use their work, particularly involving artificial intelligence technologies, to further what many see as an unfolding genocide.

But some employees say they have been met with an intense crackdown from Google, which they say has denied claims by activists that its technology has been involved or played a role in Israel's brutal campaign in Gaza and ongoing occupation – deemed illegal by the International Court of Justice – of the West Bank.

'I had colleagues who were understandably apprehensive about speaking out and worried about the consequences'

- Zelda Montes, former Google employee

The mass firings marked a turning point for the company as it grappled with an internal battle among its employees over the war in Gaza.

Middle East Eye has spoken to Googlers who work in the tech giant's offices in the US and parts of Europe. Many requested anonymity because of their concerns that they too could lose their jobs for speaking out publicly.

These workers, who work in various branches of the company, explained how they organised from within and how Google and their colleagues tried to stop their activism by censoring them, firing them, and threatening some of them by turning the company into a "hostile work environment". Some still work for the company, while others have been fired or have left in protest.

Some who spoke to MEE have been organising by themselves and with a group called No Tech for Apartheid - which has campaigned to end the Silicon Valley tech industry’s complicity in what it describes as Israel’s “ongoing ethnic cleansing of Gaza and the recent genocidal bombing of Gaza”.

Google did not respond to Middle East Eye's repeated requests for comment.

Starting as an intern, Montes worked as a software engineer at Google for two years on YouTube Search and Learning.

"Working for Google was a means to an end to survive to pay for things like rent and food in New York," explains Montes.

"And I had colleagues who were understandably apprehensive about speaking out and worried about the consequences.

"But I didn't want to be complicit, and if it meant that Google was going to retaliate against me or allow for a bunch of harassment against me to persist, then so be it."

Concerns ignored by Google

Montes, like many other colleagues in different parts of the company, started small by raising questions and concerns about whether Israel was using their work to wage its war on Gaza within their direct teams.

Early on, Montes, for example, joined other colleagues and used a YouTube town hall to question why Google was taking money from the Israeli government to run propaganda adverts, after the 7 October attacks, against the UN Relief and Works Agency (Unrwa), the United Nations agency that provides support for Palestinian refugees.

At Google and its parent company, Alphabet, town hall or all-hands meetings are company-wide and typically run in a hybrid format, allowing in-person and virtual participation to accommodate the company's global workforce.

These sessions are presented as opportunities for employees to ask leadership direct questions, fostering open dialogue about key projects, policies, and concerns.

As a company, Google has sought to make a virtue of a culture of openness that encourages employees by enabling them to raise questions and share their interests at the workplace.

'Anytime we would bring up Project Nimbus in the internal chat or during all-hands meetings, the questions would get moderated out or avoided'

- Zelda Montes, former Google employee

Yet, according to Googlers who spoke to MEE, Palestine seemed to be the company's exception.

Montes says their concerns over YouTube taking money from Israel to run "propaganda adverts" were ignored by the YouTube leadership, prompting Montes and others to try other avenues.

"People would post questions during our all-hands meetings," recalled Montes. "Anytime we would bring up Project Nimbus in the internal chat or during all-hands meetings, the questions would get moderated out or avoided."

Similar concerns were raised by Googlers who work in the company's artificial intelligence division, also known as DeepMind, but staff said these were also ignored by the company.

Ten days after the 7 October attacks by Hamas into southern Israel, Google's CEO Sundar Pichai told his employees in an email that the company planned to donate $8 million to support relief efforts in Israel and Gaza.

Pichai also used his email to condemn rising antisemitism and Islamophobia and acknowledged concerns around the rising death toll and humanitarian crisis in Gaza.

Google is no stranger to political activism within its ranks. In previous years, the company has seen walkouts by Googlers over sexual harassment claims, hate speech and its contracts with the Chinese government.

In 2018, thousands of Google employees protested a Pentagon contract dubbed Project Maven that used the company's artificial intelligence technology to analyse drone surveillance footage.

The action led Google to cave into its employees' demands and not renew its contract with the Pentagon. However, Pichai did tell his workers that the company would continue bidding for defence contracts.

In 2021, Ariel Koren quit Google after the company tried to make her relocate her to Brazil after she raised concerns over Nimbus.

Following in the footsteps of Koren and others who came before them, Montes and workers in North America and Europe began flooding internal forums and creating discussions internally about Project Nimbus after Israel began its bombardment of Gaza.

These interventions took place virtually and physically on Google's campuses worldwide.

Googlers used internal forums and mail threads to virtually connect with like-minded fellow workers in the company's offices worldwide. These forums, which take the form of mailing lists and message boards, are often divided into shared interests, identities, or causes.

"These forums were the vessels through which everything would be organised at Google," explains Montes.

Montes and fellow activists would use these networks to raise awareness and discuss the company's involvement in Nimbus.

'Whenever the words genocide or apartheid would come up, the moderators would delete the comments straight away without any warning or lock the forums'

- Alex Cheung, ex-Google employee

Like Montes, Alex Cheung was involved in No Tech for Apartheid and regularly participated in internal email threads such as Google's ethical forum to raise awareness about the project.

Both activists, as well as other Googlers who spoke to MEE, said they experienced internal censorship from Google's team of moderators who oversaw the message boards.

"Whenever the words genocide or apartheid would come up, the moderators would delete the comments straight away without any warning or lock the forums to prevent people engaging with it further," explained Cheung.

"It's like we didn't exist. Imagine the culture that is created when you are talking about a form of oppression and watching your employer delete it in real-time."

Sometimes the message boards would also be disrupted by pro-Israel staff. Some would post messages using the words genocide or apartheid in an effort to get discussion of these issues shut down, or warn other users that discussing Nimbus or Israel violated Google's policies and threaten to report participants to HR, accusing them of harassment and causing offence.

"It was so common to see message boards be shut down," explained Hasan, who is Syrian by descent and a former software developer for Google in New York.

"In the end, the managers said moderators banned the word genocide because it caused too much disruption internally - but it felt like just another form of intimidation that favoured

pro-Israeli voices."

One Googler who is Jewish told MEE that the Jewish Google group, also known as "Jewglers", would be "dominated by pro-Israeli voices who would organise against Jews who would bring up Nimbus and possible Israeli war crimes”.

Despite assurances from Pichai that the company would take issues of Islamophobia seriously, when pro-Palestine Googlers faced intimidation from pro-Israel colleagues, the company, according to them, would ignore their concerns and not take any action.

"There was a culture of ignorance from management that turned a blind eye to the abuse we would get online and offline," said Hasan.

Last November, dozens of Palestinian and Muslim Googlers signed an open letter which accused Google of "turning a blind eye" after they said Palestinians had been called "animals" and accused of "supporting terrorism" on internal forums by fellow Googlers.

It noted an example of a manager within the company's US offices who had questioned Muslim or Arab Googlers on "whether they support Hamas" or where their "sympathies" lay by supporting Palestine.

The letter also recorded one instance where an Arab and Muslim Googler was told to "refrain from making comments in support of Palestinians or even acknowledging the Israeli occupation under the guise of being 'respectful in the workplace.'"

The abuse would come in the form of confrontations in the canteen, being reported to HR and doxxed on internal pages.

One Google employee, who is from a Muslim background, told MEE that his managers singled him out after he sent an email calling on colleagues to support Palestine. This employee was issued a verbal warning by Google and was told by HR that they could be disciplined further without specifying the punishment.

The Guardian and the Intercept reported a similar incident last November when the company singled out Mohammad Khatami, a software engineer, from a group of Googlers who sent an email advertising a memorial event for Gaza. Khatami, who is Muslim, was ordered to attend a meeting with HR but declined to say what the outcome of the meeting was.

Googlers noted that the company's reaction to their activism starkly contrasted with its response to the war in Ukraine, which was noticed not just in the US but worldwide.

"When the war in Ukraine kicked off, Google sent out a message of support for Ukrainians and Russians working for the company," noted Clare Ward, who requested a pseudonym due to fears of retribution from Google.

"I just remember seeing much more visible solidarity with Ukraine with fundraising campaigns and people putting up Ukrainian flags next to their name.

"And generally speaking, some people have a Palestine flag or a 'Free Palestine' next to their name, but that is not without internal threats from managers warning us off about being public with our support for Palestine.

"Generally, there was an open political space that allowed us to speak freely and openly about political issues. But nowhere near as much moderation and shutting down of conversation as we have seen with Palestine."

When the censorship took place virtually, Googlers slowly moved their activism away from the keyboard and onto Google's campuses.

This activism would take the form of "tabling," where Montes and other Googlers in the US, London, and Amsterdam would sit in the canteen during the day with a sign that read "Ask me about Nimbus" to educate and encourage colleagues to sign a petition.

"People would come up to us often to ask what Nimbus was, and we would happily talk to them because the company doesn't tell them about it," explained Montes.

The activists would try to organise events and film screenings to educate their colleagues about Palestine. Google's management shut down these events, irrespective of whether they were in London or Los Angeles, citing safety concerns.

One screening, scheduled to take place during Arab Heritage Month in April 2024, was among events cancelled by Google.

Firing of workers

Things came to a head when Israeli bombs killed a Palestinian software engineer, Mai Ubeid, and her whole family in Gaza in late October 2023. Ubeid graduated from a Google-funded coding boot camp in Gaza called Sky Geeks and later interned at a firm that was part of the Google for Startups accelerator in 2020.

Googlers organised vigils outside its offices in New York, Seattle and London for Ubeid, who was disabled and wheelchair-bound.

These vigils were met with hostility from Google and colleagues. Ward, who worked from the London office, noted an instance where a pro-Israeli employee "harassed" Googlers handing out leaflets about the vigil for Ubeid.

Like other Googlers who spoke to MEE, Ward said her manager had encouraged her to stop organising for Nimbus and speaking out against the project.

Some were issued warnings by their managers for handing out leaflets related to Ubeid and reminded of the company's policies against leafleting on company property. They believe Google used CCTV and pictures taken by pro-Israel colleagues who sent them to human resources to identify them.

Some relayed concerns by their peers that they were "afraid" to speak out because their senior manager had previously served in the Israeli army’s Unit 8200, an elite Israeli intelligence unit that specialises in cyber espionage, surveillance and intelligence gathering.

Like many tech companies, Google has a track record of hiring former members of Unit 8200, many of whom go on to careers in Israel’s own thriving tech sector and are highly regarded for their technological skills.

Hostility at the workplace became so severe that Googlers began meeting off-site to plan next steps to organise - including passing petitions in person to avoid any backlash from Google.

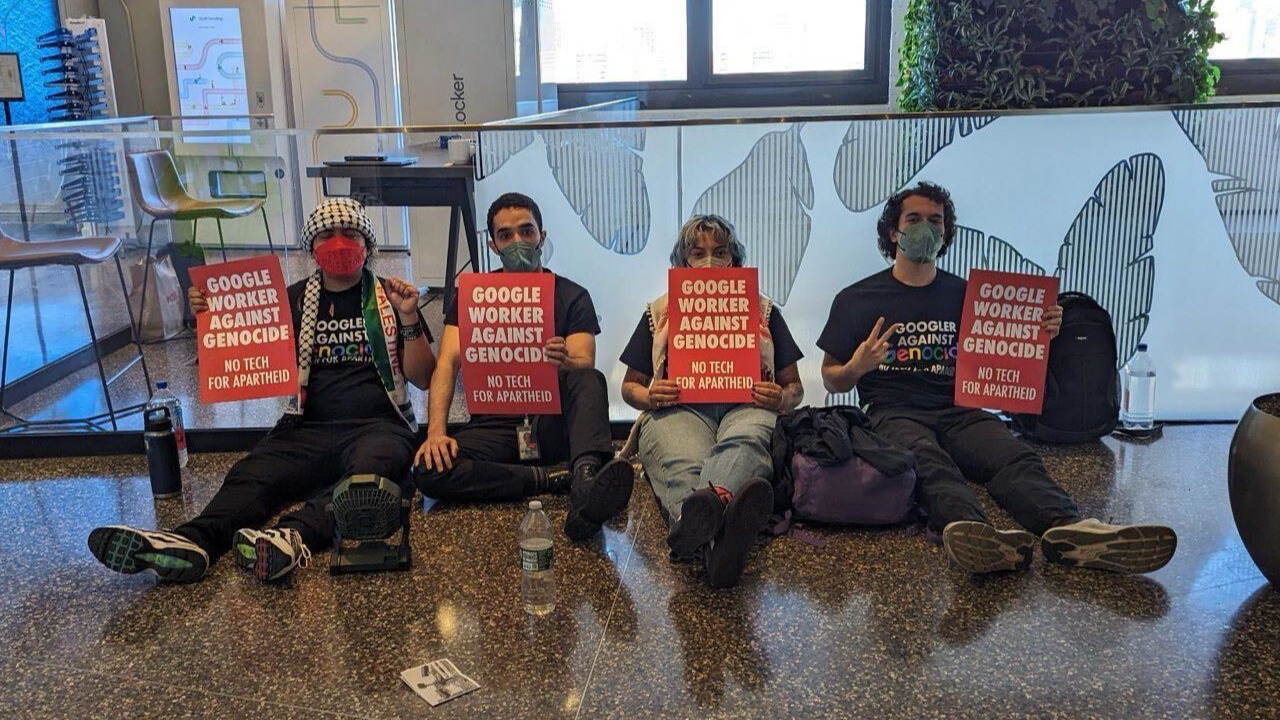

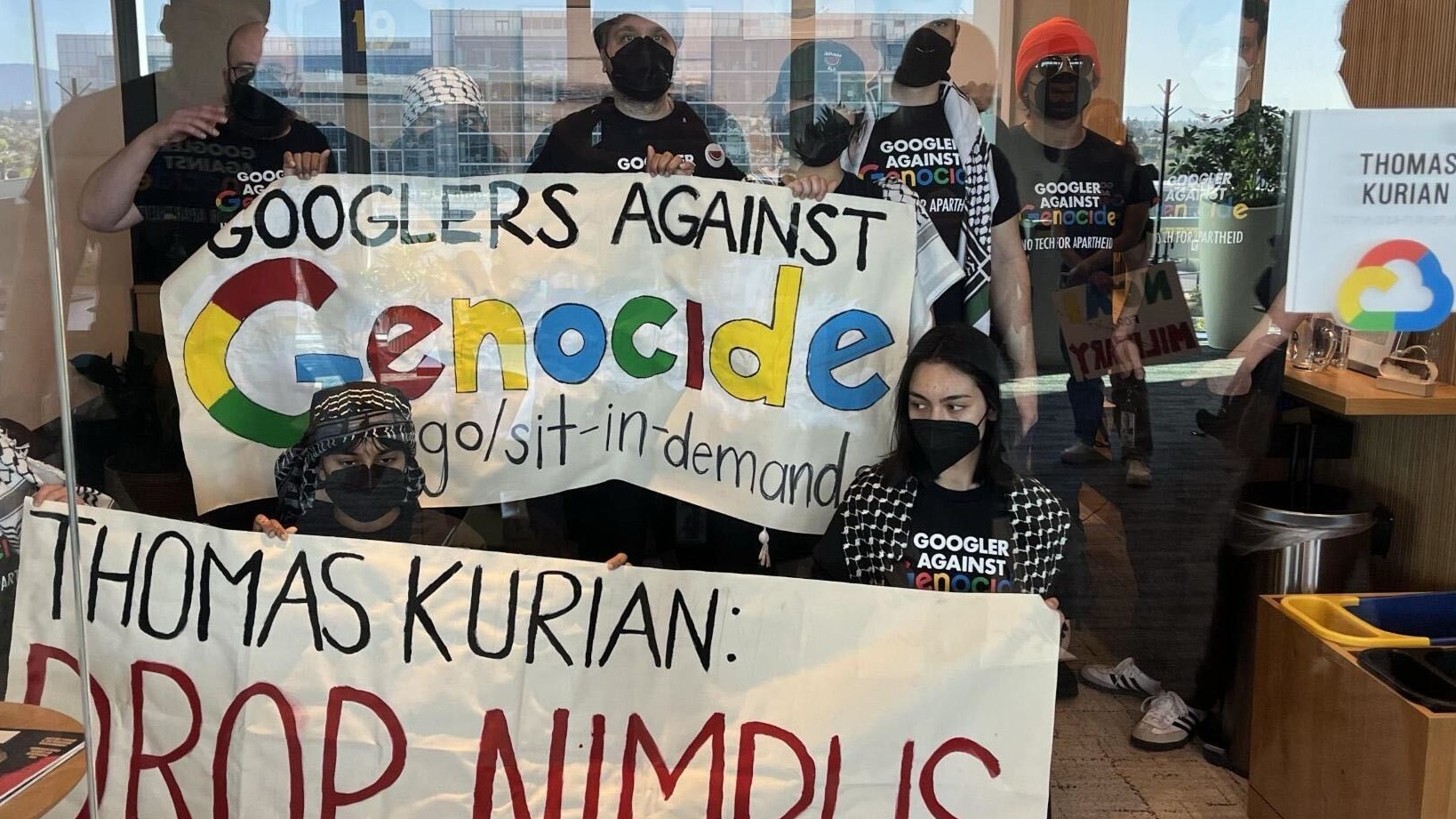

Workers, including Montes, Cheung and Hasan, decided to stage a sit-in at the company's offices in New York City and Sunnyvale, California. Activists occupied the entrance to the company's offices and the office of Google Cloud chief executive Thomas Kurian for 10 hours.

'We believe, as the IDF claims, that Google's cloud tech is giving Israel a significant technical military edge, and we don't want to be involved in that'

- Oscar, Google DeepMind worker

The company called in the police and fired 28 workers on the spot and 22 others after an investigation that involved analysing CCTV footage.

The day after, Chris Rackow, Google's head of security and a former US Navy Seal, sent a memo warning employees to "think again" if they planned to protest in its offices.

But despite the firings and months of intimidation, many remaining Google workers are determined to continue their campaign against Nimbus.

Google did not respond to questions on why it fired the employees but told the Guardian at the time: "We continued our investigation into the physical disruption inside our buildings on April 16, looking at additional details provided by coworkers who were physically disrupted, as well as those employees who took longer to identify because their identity was partly concealed – like by wearing a mask without their badge – while engaged in the disruption.

"Our investigation into these events is now concluded, and we have terminated the employment of additional employees who were found to have been directly involved in disruptive activity.”

'Existential crisis'

In August, more than 200 workers inside Google DeepMind signed a petition urging the company to drop Project Nimbus and pledging to never work on military contracts.

Oscar, who declined to give his surname, signed this petition and noted that DeepMind's leadership had not responded to the petition directly.

Based in the UK, Oscar was more confident that his job would be safe if he openly spoke about Nimbus because of British laws protecting workers' rights. But he acknowledged his activism would "limit" his career progression within DeepMind.

"It feels like being in a golden prison. We are compensated very well working for DeepMind. I worked hard to get to my position, but for the first time in my career, I feel very uneasy with what we are doing," said Oscar.

"We believe, as the IDF claims, that Google's cloud tech is giving Israel a significant technical military edge, and we don't want to be involved in that.

"Many researchers and engineers at DeepMind don't want our AI models being used for military purposes and DeepMind still claims it's not happening, despite our models being taken having no visibility on how that gets used."

Many within DeepMind and Google believe Nimbus is a small part of Google's strategy.

Ward acknowledged that an AI arms race and the emergence of Open AI's Chat GPT is forcing Google to re-evaluate its identity as a company because they are having "an existential crisis”.

"If you look at the tech landscape right now, Google is losing the battle over artificial intelligence and how people are using it," said Ward.

"My manager would bring up Chat GPT and Open AI every other day. There is pressure from the top and we feel it on the ground level."

Oscar echoes Ward's reflections on the company, highlighting DeepMind's pivot towards creating AI products like Chat GPT, and believes Nimbus represents something more significant for Google.

"The money we know of for Nimbus is not big, but it sounds like they just want to position themselves for military contracts in general," said Oscar.

"They will not be backing down. That is more important to Google than what a fraction of employees in the company think.”

Main photo: A demonstrator wears a Google-themed protest T-shirt in Seattle in May 2024 (Reuters)

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.