Salt Journals: Tunisian women describe their country’s legacy of political imprisonment

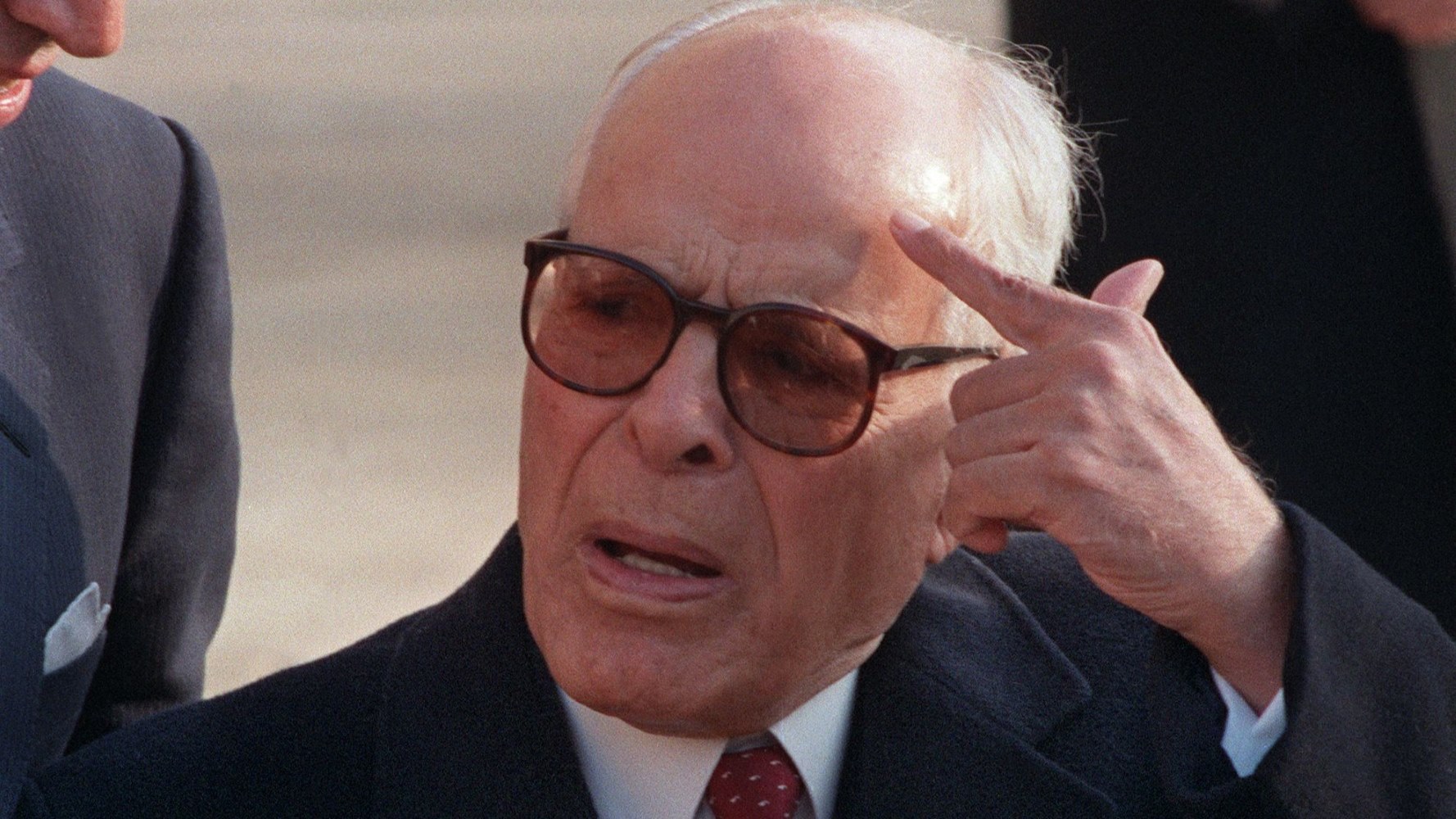

In more than a dozen short stories included in Salt Journals, a diverse group of Tunisian women chronicle their experience of political imprisonment under the presidencies of Habib Bourguiba and Zine el Abidine Ben Ali.

Together, they overcome silence, question the legacy of political oppression in the country and apply a gendered lens to violations that continue to shake Tunisian aspirations for freedom and dignity.

Each chapter is authored by a different writer and the women’s voices often reverberate and bleed from one story into another, alternating between fictionalised selves and testimonials.

In that way, the book forms a rhythmic compilation of sorrow.

Salt Journals contends with the carceral experience both within and outside the prison walls.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In these stories, political detention is considered a collective disruption that impacts families and communities.

But it is also a personal, intimate, life-altering event, especially when the women themselves become inmates.

Salt wounds

Salt Journals quickly dives into a “real Tunisia” very different from touristic cliches, a Tunisia occupied by towering characters like informers and prison guards, and furnished with an illogical landscape that requires careful negotiating.

In The Girl Who Won’t Grow Up, Nouha Dimassi describes a girl raised without her imprisoned mother. In this story of abrupt parting and uneasy reunion, the child tries to recognise her mother when she returns amidst a persistent feeling of estrangement.

“It was the childhood of a girl without a mother and an outcast from a society that either wanted to avoid getting into trouble with the state or really did believe that her mother was a traitor to her country,” Dimassi writes.

“The memories are obstinate, fading a little, only to reappear with resolute cruelty,” she adds, capturing mixed emotions of guilt, alienation and resentment, and the aftermath of state violence on family bonds.

Women are often the caretakers and the familiar Tunisian quffa - a basket used daily to carry groceries from the market also associated with wedding ceremonies - becomes an embodiment of hardships, steadfastness and courage.

Often taking personal risks when visiting imprisoned family members hundreds of kilometres away from their home, women carry their quffa filled with food and memories. Yet the quffa is also a symbol of abuse and bribery as prison staff regularly harass visitors.

“My biggest worry was looking after the quffa,” writes Hasna Ben Abid in Hasna’s Quffa.

She describes a “basket of torment and pain”, which she ends up spilling on the ground after a gruelling journey before having a chance to hand-deliver it to her husband in prison.

Tears ran down her exhausted face.

The collection also includes a poem, The Heart’s Path by Jomaa Ben Ali, in which a woman reminisces about her imprisoned father. It also brushes upon more evocations of prison life that confront torture and rape, denouncing a crushing system of expeditive judgments and arbitrary detentions.

This is also the case with other stories.

“The judge sentenced me to prison based on a search report that was finalized a half hour before I appeared in court before him,” writes Najet Gabsi in Hot Water.

“Our dad had no connection to politics or its people other than the party he was forced to join, brow-beaten by its local chairman into paying the membership fees of all the adults in our family once a year, and placing an inky finger on the ballot slip when elections came around,” Soulefa Mabrouk writes for her part, on a democratic facade that Tunisians know too well.

Arab political imprisonment as a literary genre

Salt Journals, like other narratives within prison literature, engages with transgression, power and violence. Because the stories are narrated from women’s perspective, they seek to break social taboos.

The book features the words of women from various parts of the country, aged from their twenties to their sixties.

They were encouraged to explore their experience and memories through a series of creative writing workshops, a collective experience also reflected in the book process with several editors and translators involved in the project.

“The women have either remained silent or been silenced for several political, societal, and familial reasons that include the imposition of patriarchal morality codes of shame, the protection of family members, a lack of confidence in one’s own power of self-expression, political intimidation by the state, and the gendered relegation of free expression and political protest to the invisibility of private space,’ explains Brinda J Mehta in her introduction.

Salt has a double symbolism here - evoking both tears and the condiment that enhances flavour. Through the act of writing, women relive their trauma thus pouring fresh salt onto their visible and invisible wounds.

Haifa Zananga, one of the book’s editors, spends time establishing who these women are and their challenges, such as overcoming a fear of writing and navigating French, colloquial Tunisian and formal Arabic.

Zananga’s foreword sometimes veers towards essentialising womanhood and these women’s experiences, including through unnecessary stereotypes, for instance referring to “an atmosphere of Scheherazadesque storytelling”.

“We learned to be faithful in descriptions of events and other people; and we tried to avoid making the self a heroic figure at the expense of others,” Zananga writes, recalling the workshopping process.

Women wearing so-called sectarian outfits faced a number of consequences, from petty insults and humiliation to being prevented from accessing or retaining public jobs

All writing is an act of fabrication and subjectivity and in many ways, the book can be approached as a meta narrative on language and why writing matters.

Writing in this context wants to be principled: to amplify political resistance and uphold a degree of moral integrity. There is no voice granted to women prison guards or women informers.

The collection wants to set a record, bear witness and oppose depersonalisation and the fear of forgetting.

As an act of memorialisation and self-affirming agency, testimonies such as these can indeed directly contribute to a transitional justice process of truth-telling, reparations and healing.

Nawal el-Saadawi demonstrated this potency in her Memoirs of the Women’s Prison about her time behind Egyptian bars in 1981.

Fatna el-Bouih also wrote of forced disappearance during Morocco’s Years of Lead in Talk of Darkness.

While women’s activism upends traditional norms of compliance and obedience, their writing is also significant when it interrogates who gets to be an outcast or an outlaw in an authoritarian regime, which Salt Journals does.

Yet the stories contained in the book can be uneven, with their concise, vignette-like format often preventing the emergence of more complex character development as well as a deeper exploration of key themes such as forgiveness, grief and dilemmas.

In their glimpses, the writers superbly illustrate the absurdity of dictatorship, its pervasiveness and destructive power.

Beyond these women, we think of today’s urgent transnational solidarity, from Alaa Abd el-Fattah to the countless Palestinians arbitrarily detained in Israeli prisons under inhumane conditions.

The question of why someone is arrested is as haunting as the torture rooms that words can feel inadequate to describe, even decades later.

An inventory of Tunisian state repression

Against the backdrop of political imprisonment narrated in Salt Journals is the hardening of dictatorship in post-independence Tunisia, which created categories of citizens and labelled some enemies from within.

Dissent must be quenched, even more so when there are affinities with political Islam involved or other challenges to the state’s secular doctrine.

Salt Journals often recalls the impact of Bourguiba’s Circular 108 which banned Tunisian women from wearing the hijab in public schools, universities and public administration in 1981 when the Islamist party Ennahda was founded.

This secularist policy was also enforced during Ben Ali’s regime.

Women wearing so-called sectarian outfits faced a number of consequences, from petty insults and humiliation to being prevented from accessing or retaining public jobs.

Far too many were also detained following farcical trials.

Stories in the book also remember the removal of subsidises and consequent brutally repressed bread riots of 1983 and 1984, which resulted in the death of 100 people. But Salt Journals isn’t just about Tunisia’s pre-revolutionary history.

More than a decade after the 2011 revolution, the autocratic rule of Kais Saied has reawakened the former regime’s worst tendencies.

A year after unilaterally suspending the parliament in July 2021 under a state of emergency, Saied enacted the controversial Decree Law 54 to combat misinformation online, a measure largely perceived as an attempt to intimidate and prosecute critics and further stifle freedom of expression.

State harassment of Ennahda figures has continued since, expanding to other political opponents and human rights defenders including the recent arrests of politician Abir Moussi, lawyer and journalist Sonia Dahmani and prominent anti-racist activist Saadia Mosbah - a new wave of women political prisoners.

Dahmani was sentenced to two years in prison in late October this year on accusations of “inciting hatred”.

Amidst such significant setbacks, Salt Journals is a timely contribution to remembering and combatting democratic reversals. On the Margins of the Path by Mounira Ben Kaddour Toumi offers a reflection on political violence and consent. She writes of the 2011 revolution:

“For the first time I had a sense of belonging and felt real pride to be part of this people and this country. I realized that silence in the face of oppression and injustice was not cowardice but extreme tolerance and forgiveness and that being content with little was a sign not of weakness but of love for the homeland.”

Fear may have returned in Tunisia but perhaps not for long.

“My country didn’t have a revolution so as to bring back idols,” notes Khadija Salah.

Salt Journals: Tunisian Women on Political Imprisonment is published by Syracuse University Press

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.