Terror in Nabatieh: On the front line of Israel’s war on Lebanon

On a hilltop in Lebanon’s southern city of Nabatieh, rescue workers stood on standby, ready to respond to the near-constant Israeli air strikes below.

The destruction sprawled out in front of their eyes: homes, workplaces and the city’s near thousand-year-old market reduced to piles of charred rubble.

They had just spent the previous night and day rushing to extinguish fires following over 10 Israeli strikes on the small southern city in less than 24 hours.

Ambulances, fire trucks, and other rescue vehicles were parked nearby. Some of the vehicles had been damaged in Israeli air strikes. Their windshields were cracked, doors dented, windows sometimes replaced by sheets of loose plastic.

Many of the rescue vehicles were damaged on 16 October, when Israel pounded the centre of Nabatieh, the main city in the Jabal Amel area, with consecutive air raids, the head of Nabatieh’s civil defence force, Hussein Fakih, told Middle East Eye.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The strikes targeted the city’s municipal building, killing its mayor and at least 15 others, with 52 people wounded.

That day, Fakih and his team rushed to help the victims, but while they were clearing bodies from the rubble, an Israeli air strike hit an adjacent building, wounding him and six of his colleagues.

Fakih, 52, spent 18 days in hospital - including seven under intensive care - for severe wounds to the head and lungs.

Just days after being discharged, he was already back on the job.

“We have to continue our work, although what is happening is unacceptable,” he said. “There is no respect for the protection of rescue workers or medical staff.”

As of 25 October, Israeli attacks have killed at least 163 health and rescue workers across Lebanon and damaged 158 ambulances and 55 hospitals, according to Lebanon's health ministry.

Another Israeli attack on 16 October hit just 40 metres from a civil defence centre in Nabatieh, wounding three more rescue workers and killing one, 30-year-old Naji Fahes.

“He had two children,” Fakih said quietly, remembering his friend and colleague.

“We are experiencing a great loss,” he said, “because these men are heroes, in every way.” Choking up, Fakih turned around to catch his breath before he could continue the interview.

After a few minutes, he turned back around and said: “Despite the strikes, the obstacles that are happening, and all the suffering, the civil defence workers remain present… Citizens depend on us to save them.”

‘Every day our work is becoming harder’

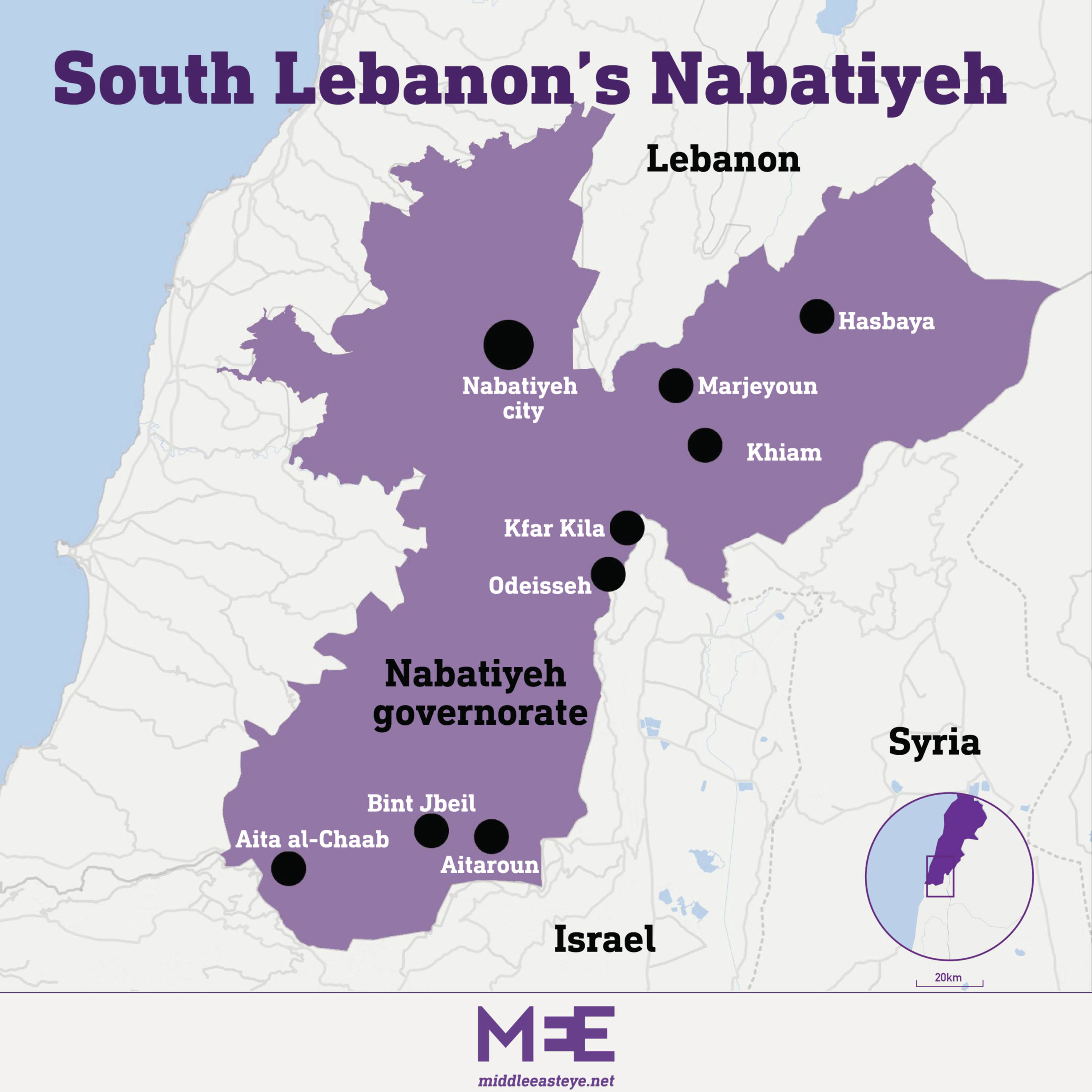

Fakih heads rescue operations from 21 civil defence centres located in different cities throughout the southern Nabatieh governorate, including in several border towns devastated by Israel’s air strikes and ground invasion.

'We are experiencing a great loss because these men are heroes, in every way'

- Hussein Fakih, civil defence chief

Lebanon’s National News Agency (NNA) reported on 5 November that the Israeli army had razed 37 villages in southern Lebanon and destroyed more than 40,000 housing units, in an area three kilometres deep along the border.

At least 3,243 people have been killed in Lebanon since fighting between Israel and Hezbollah began in October last year, according to Lebanon's health ministry. Most have died since 23 September, when Israel launched a wide-scale bombing campaign across Lebanon and a ground invasion.

With more direct Israeli attacks on first responders, Fakih said their work has become increasingly deadly. “Every day our work is becoming harder than the last,” he said.

He noted that 13 civil defence personnel working in southern Lebanon have been killed and around 46 wounded since the start of the fighting.

Fakih estimates that Israel’s direct targeting of rescue workers has increased since around 9 September, when a strike killed three clearly-designated paramedics extinguishing fires in the southern town of Faroun.

The Israeli army has on multiple occasions threatened to target ambulances in southern Lebanon, accusing them of allegedly “transporting” Hezbollah fighters and weapons.

A recent Human Rights Watch (HRW) report documented three attacks in which Israeli forces “unlawfully” struck medical personnel, transports, and facilities. HRW did not find any evidence indicating the use of these facilities for military purposes at the time of the attack.

Over the course of 24 hours, on 9 and 10 November, Israeli strikes on paramedic gathering points and civil defence centres killed 10 rescue workers from the Hezbollah-affiliated Islamic Scouts and the Islamic Health Association.

HRW reiterated in its report that membership or affiliation with Hezbollah, or other political movements with armed wings, is not sufficient basis for determining an individual to be a lawful military target.

“The Israeli military should immediately halt unlawful attacks on medical workers and healthcare facilities, and Israel’s allies should suspend the transfer of arms to Israel given the real risk that they will be used to commit grave abuses,” HRW said.

Fakih said his rescue teams are “constantly repositioning and spreading out” to avoid an attack resulting in a mass casualties of rescue workers. Also, his teams usually wait five minutes if there are no confirmed civilians at the scene of a strike.

“We must protect these [first responders] so they can continue to rescue others,” he said.

The Burn Unit

Fakih and his teams often rush people they rescue in Nabatieh city and the surrounding areas to Nabih Berri public hospital, a few minutes drive from their lookout on the hilltop.

Since 23 September 23, when Israel escalated its attacks across Lebanon, the hospital has treated around 1,200 people wounded in nearby Israeli strikes, the hospital’s director, Hassan Wazzani, told MEE.

'We have to pull out the dead bodies of people we love, friends and families we know, neighbours, people from our own area'

- Hussein Jaber, civil defence

Fakih was one of those patients.

The hospital also has one of the country’s two leading burn units. Wazzani said that in addition to “injuries to the head, abdomen, legs and arms”, victims of Israeli air strikes also often have severe burns.

One of the two patients in the burn unit when MEE visited was 29-year-old Mohammad Ahmad Nazar, receiving treatment for second and third degree burns all over his body. A large piece of shrapnel had also ripped through his right leg, leaving him with several stitches.

His voice was faint, and he looked to be in pain as he spoke. Two days earlier, when MEE first visited on 7 November, he was in so much pain he could not utter a single word.

Around three weeks earlier, Nazar and his two friends were home making dinner for their neighbours in their village Arab Salim, about 10kms from Nabatieh city.

The young men had been serving food almost every day to these people, who Nazar said had been “left behind” and did not have family or relatives to care for them.

But that evening their benevolent act was interrupted by an Israeli missile barrelling into the house next door and sending their home up in flames.

“The moment we were hit, I felt the air pressure hit. Suddenly you lose all senses, no vision, anything,” Nazar said.

One of Nazar’s friends, Ali, was killed in the strike. He was about Nazar’s age.

Nazar said that once he heals he will still return to Arab Salim. “It’s my village,” he said. “It’s scary, but we have nowhere else to go.”

‘Tired of being strong’

In the room next to Nazar, Saadoun Barakat, 52, had been hospitalised in the burn unit for over a month when MEE visited.

His left arm, which was covered in second and third degree burns, was still heavily bandaged. Blood was crusted at the end of the bandage, where a few of his fingers poked out.

An Israeli air strike on 24 September hit his home in the southern village of Marjayoun. His brother Khalid, sitting next to him in the hospital room, said that at first, the burns had left him unrecognisable. He showed MEE a photo of Barakat soon after the strike, his face dark purple and eyes swollen shut.

“There was a burning pain… When the missile first struck it was like hell,” Barakat said from his hospital bed.

The cost of long in-patient stays, like Barakat’s, would be exorbitant if the Ministry of Health did not cover it, Wazzani, the hospital director noted. For instance, one day in the burn unit costs around $500, he said.

The director worried that the hospital wouldn’t be able to sustain the costs for an extended period: “I don’t know if in the future, they will have money. We’re in an economic crisis.”

Meanwhile, sonic booms from Israeli jets breaking the sound barrier shake the hospital’s windows nearly every day.

The booms, which mimic the sound of explosions, gave Barakat panic attacks, Ali Omeis, the hospital's supervisor, told MEE.

Just a week after Barakat was admitted, the force of a strike a kilometre away in Nabatieh caused parts of the ceiling to fall in front of his hospital bed - shocking the already-traumatised patient.

Omeis said that only heavy drugs like morphine and alprazolam (an anxiety medication) could ease his intense pain and panic.

On the way down from the burn unit, Omeis commented on the hospital staff’s own physical and psychological exhaustion from the war and consecutive crises in Lebanon.

“We’re tired of being strong,” he said. "From Covid, the financial crisis, and now this war.”

‘Mentally, we are all struggling’

Back at the hilltop, Fakih’s colleagues also spoke about the immense stress and psychological pressure they were under.

“Mentally, we are all struggling,” Hussein Jaber, 30, from Nabatieh’s civil defence, told MEE.

“We are struggling with the lack of stability. We are always on the move, can’t sleep well, and are being put in intense situations,” he said.

“We have to pull out the dead bodies of people we love, friends and families we know, neighbours, people from our own area.”

From the back of an ambulance, Jaber pulled out a tattered fire suit and broken helmet. He said it was Naji Fahes's gear, which he was wearing when he was killed on 16 October.

“We are doing our jobs and feel responsible for saving people’s lives, yet we are in great fear because we are also being targeted,” Jaber said.

Once the conversations finished, silence fell over the hilltop, broken only by deadly hum of an Israeli drone. The rescue workers simultaneously looked to the sky, trying to spot it.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.