Slavery in Mauritania: Differentiating between facts and fiction

Over the past few years, Mauritania has made headlines frequently in world news. These occasions were not due to the country’s frequent coups, but rather the issue of slavery. In 2012, a CNN documentary described Mauritania as “slavery’s last stronghold”. The documentary, which was based on John D Sutter’s three-day visit to Mauritania, estimated that from 10 to 20 percent of the population were enslaved. Driving through the “reel of emptiness” for hours without seeing anyone, Sutter concluded that the country keeps 340,000 to 680,000 people, out of a population of 3.5 million, in bondage and hidden from the outside world.

Another report calls this population of slaves “Mauritania’s best kept secret”. Sutter’s most recent article presents a new estimate for the percentage of Mauritanians enslaved: four to 20 percent. It is not clear why the lower digit is now four percent instead of 10 percent.

Recently, Middle East Eye featured two articles on slavery in Mauritania. One article spoke of 150,000 Africans enslaved by the Arab minority. The author, Michael Phillips, drew a parallel between the apartheid of South Africa and the Mauritanian case. He claimed that Haratine are denied access to schools, which is anything but accurate.

Members of the Haratine community do have equal access to universal education and to other state services, but they are often unable to benefit from them due to various impediments which are exacerbated by rampant corruption and nepotism.

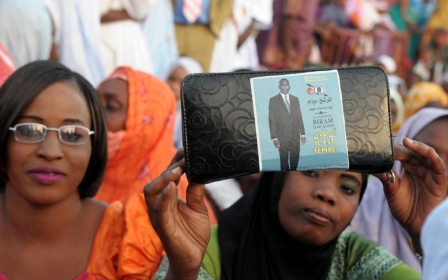

Phillips lavished praise on the former presidential candidate and anti-slavery activist Birama O. Abeid[1], calling him a modern-day Mandela. He highlighted Abeid’s heroic acts against slavery, including the burning (of what Phillips thought were) pro-slavery books by the eighth-century Medinan jurist Malik B. Anas.

Beyond these factual errors, the issue of Mauritanian slavery deserves inquiry. Does this small West African country of 3.5 million people truly have a huge population of slaves? What does slavery really mean in the Mauritanian context? What kind of legal framework is in place to protect people from the scourge of human exploitation and forced labour?

We should make clear at the onset that our intent is not to deny the real suffering of a community, much less whitewash a cumbersome historical legacy. Our goal is limited to elucidating a complex social phenomenon, by painting a more nuanced picture where the dynamics at play are exposed. This is simply a better one - far closer to reality than the picture most often painted and hyped in the press.

What we hope to convey is that the figures published by international organisations about slavery in Mauritania are not only exaggerated but lack any real statistical sources. As the example of the Global Slavery Index (discussed later in this article) shows, the absence of solid data doesn’t deter these organisations from making wild claims. Despite the absence of reliable data, our keen knowledge of the legal and social vicissitudes in Mauritania since independence leads us to believe that the numbers of slaves are far smaller than the numbers currently circulated.

Yet we believe that no matter how small the existing slavery pockets are, real measures must be taken to address that issue. Creating sustainable development programmes to better the lives of the larger and already emancipated Haratine will help drain these pockets, since there are no legal or administrative hurdles preventing the emancipation of the rest.

The context

Mauritania is a vast stretch of land, sparsely populated yet ethnically and culturally diverse. The country is located at a major geographical crossroad separating two distinct regions: the Maghreb and Sub-Saharan Africa. Historically, the country was also an ancient trade route and hence a convergence for a variety of influences. The modern country still bears the enduring hallmarks of these influences.

One of the key features of Mauritania is an age-old social stratification that stands as a reminder of the country’s deeply entrenched African roots. At the heart of that system was the practice of slavery, whose lingering effects continue to fuel controversies at home and bring unwanted attention from abroad.

While the historical institution of slavery in Mauritania has crumbled, its residual effects continue to trouble the country and relegate former slaves - the Haratine - to a subaltern status. Although this very real problem receives less attention than it deserves, the international press and human rights organisations continue to stoke controversy over the issue of slavery using outdated stereotypes and shoddy statistical methods.

It used to be said that the French always fight the last war. In a similar fashion, the international organisations are addressing a problem of formal slavery that has mostly ceased to exist, while ignoring the legacy of slavery and the plight of former slaves. The misapprehension of the problem is compounded by a general lack of understanding of the Mauritanian social structure and the nature of the institution of slavery in the Mauritanian traditional nomadic society.

The concept

Historically, slavery in this context is not the same type of human exploitation (involving systematic torture and segregation) as that which formerly took place in Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi, for instance, or even in the Caribbean islands. In the Mauritanian case, slavery was a particular form of rural fiefdom within an agro-pastoral lifestyle, marked by social stratification and division of labour. Both landowners and livestock owners retained dependents who provided labour, tilling the land or tending the herds in exchange for sustenance for themselves and their dependents. Slaves were one unique segment of that system of interdependence; their dependence was both permanent and inheritable, unless bartered or sold.

Despite their subordinate status, slaves lived and travelled with their masters and often shared the same domiciles. That system endured for many centuries, but in the past five decades, it has been in a steep decline. Although social clichés and cultural stereotypes persist, their translation into exploitation has become marginal over the years because of the rapid social and urban transformations the country has undergone. Mauritania, where 95 percent of the population was nomadic on the eve of independence in 1960, has become largely sedentary. Today, nomads constitute less than five percent of the population.

It is in the encampments of these few remaining nomads and the small villages on the periphery of urban life that vestiges of slavery may continue to exist. Given the absence of dependable statistics, their numbers are hard to determine. However, due to the country's fast-paced social transformation in the past decades, we believe a more realistic estimate for the number of remaining slaves in Mauritania is several thousand.

Law and slavery

In part, the collapse of slavery and the social transformations that accompanied it were brought about by numerous legal interventions from the state. Legally, the practice was banned on several occasions. For instance, Mauritania ratified in 1961 the convention against forced labour (N 29, 1930), having already enshrined abolition, albeit implicitly, in its 1959 constitution. A more explicit abolitionist decree (N 81-234) was passed by the military junta of President Haidalla in 1981, along with agrarian reform. This decree was justified on Islamic legal grounds and supported by the clerical establishment. Another law (N 025/2003) was passed in 2003, instituting penalties for crimes of human exploitation. These laws were further bolstered in 2007 with stricter legal measures, criminalising all forms of forced labour. In April 2015, a new law increased the penalty, in certain cases, from five to ten years in prison, and included new features to make Mauritanian law fully in compliance with international legal conventions.[2]

Despite that legal arsenal, the missing element remained the absence of robust implementation and monitoring mechanisms. As a result, the impact of these progressive policies was, for the most part, modest.

Although technically free, the descendants of former slaves (Haratine) continue to live in difficult socioeconomic conditions, making up the lion’s share of slum-dwellers and a majority of the unemployed.

Slavery and ethnicity

Further complicating the issue of slavery is the perceived racial character of the slave-master relationship in Mauritanian society. This is precisely why a similar practice of slavery within the Mauritanian African community, where both slaves and their masters share the same skin colour, is mostly overlooked both as an area of research and as a sphere of state intervention.

The political upheavals - which in the late 1980s led to extrajudicial execution of Afro-Mauritanian officers and the expulsion en masse of civilians in the early 1990s - have contributed to a conception of a slavery-race correlation by outsiders unfamiliar with the complex anthropological landscape of the country.

A vocal segment of those who were unjustly expelled proceeded to claim they had been enslaved to secure refugee statuses and international sympathy, although almost none have ever been enslaved. Some in fact had their own slaves. We have heard several testimonies to this effect from Mauritanians in the diaspora. This same strategy was even used by some Moorish individuals to obtain similar privileges in the West. Yet, the readily recalled stereotype of whites enslaving blacks became the most salient view of an otherwise complex system of social stratification.

Despite these shortcomings, an attenuation of racial tensions - including the ones arising from the increasingly pressing Haratine problematic - starts with an appropriate resolution to the Negro-Mauritanian issue. Addressing the legitimate grievances (political and identity claims, etc) of this community would be a good starting point.

The human rights organisations’ chorus and their statistics

As we stated earlier, the numbers circulated about Mauritanian slaves by international human rights’ organisations range from four percent to more than one-fifth of the population. These figures are fictive, but how do international organisations generate them?

The first thing to note is that the government of Mauritania doesn’t disclose any information about the ethnic constituents of the population in its census. Of course, a government this guarded about ethnic data is very unlikely to publish information about a phenomenon these reports claim it goes to extreme measures to conceal.

The second important fact is that no international agency of any standing has ever managed to conduct a census in Mauritania about slavery. All of the international agencies’ data about the country’s population come from the Mauritanian Office of Statistics.

Of course, international slave hunters and local NGOs could carry out surveys to produce estimates of the population in bondage. But no NGO has demonstrated that it has done so. International and local activists as well as researchers who came to Mauritania to find slaves have ended up citing two or three cases of slavery, which get repetitively cited to make claims of widespread slavery.

It is true that one person in bondage is one too many, but in a country where up to one-fifth of the population is supposedly enslaved one should easily find hundreds of cases.

In the absence of real cases and authentic data, international organisations rely on unreliable figures provided by locals who neither have the technical know-how nor resources to carry out real surveys. Yet, these individuals’ careers depend on the impression of a widespread slavery. Their estimates suggest that they substitute the paucity of information with guestimates, where descendants of former slaves who are no longer in bondage are counted as slaves.

Since their information clients demand no real statistics, the locals’ various approximations are what end up filling the pages of international organisations’ press releases. This explains the rarity of cases, contradiction of narratives and wild variance in slavery figures (10-20 percent or four-20 percent, for example).

Furthermore, most of the cases brought before Mauritanian courts often turn out to be cases of labour malpractices rather than cases of bondage. The US Department of State, whose omnipresent gaze (via the US Embassy) in the small Islamic Republic is ever watchful for issues of this nature, has been using the more neutral phrase “slavery-like practices” in its annual report since 1999.

In fact, the 1999 report mentions that “Anti-Slavery International has stated that there is insufficient evidence one way or the other to conclude whether or not slavery exists, and that an in-depth, long-term study was required to determine whether the practice continues.” Slavery should have been in decline since, but in these reports it keeps rising, although no in-depth studies of any sort have been done.

Even as it scolds the Mauritanian government for its laxity in implementing its anti-slavery laws, the majority of the US Department of State’s (DOS) reports conclude that “a system of officially sanctioned slavery in which government and society join to force individuals to serve masters does not exist.”

In contrast to the Arab-Black/master-slave binary, some DOS reports suggest that slavery is likely to be found in the south: “Widespread slavery was traditional among ethnic groups of the largely nonpastoralist south, where it had no racial origins or overtones; masters and slaves alike were black.”

This view is based on the DOS’s belief that even before slavery was banned in the 1980s and before the majority of the population became sedentary, “slavery among the traditionally pastoralist Moors [Arabs] had been greatly reduced by the accelerated desertification of the 1970s, [since] many white Moors dismissed their former black Moor slaves because the depletion of their herds left them unable either to employ or to feed slaves.” This contradicts Phillips’ suggestion that slavery is practiced by an Arab minority against Africans.

Contradictions

From an uncertainty about the existence of slavery, to a perception of its prevalence among Africans in the south where masters and servants are black, to a contrasting assertion that Arabs expect servitude from blacks, the portrait of Mauritania’s best kept secret appears to have been painted in a dark room of ignorance, via the opaque ink of neoliberal policies by the latter-day saints of Orientalism.

To their credit, the reports of DOS remain relatively cautious, but they and others provide a background for a slew of cherry-picked quotes, running in a circuitous manner. For example, the numbers that MEE’s recent article cites - although smaller than the numbers cited by CNN’s - came from a report by the Global Slavery Index, but the article says little about how the Global Slavery Index obtained that information.

Despite placing Mauritania on the top of the list, the Global Slavery Index’s methodology paper admits the shaky foundations of that ranking: “no random sample survey information is available; no census has been performed in the country for some time (even the number of people in the total population is in doubt).” The only justification for the speculative four-percent rate is that it is more conservative than the wild 10-20 percent range found in the reports of the local NGO SOS-Esclaves and BBC, neither of which conducted empirical surveys in the country.

Global Slavery Index’s methodology paper explains this reduction as follows: “Because of these caveats, the Walk Free Foundation retained the more conservative estimate used in the 2013 Index. This proportion of the population estimated enslaved is 0.04.” It is not clear why the conservative percentage should be four percent as opposed to five, six, or one on the continuum from ten to zero.

In the chain of statistics’ production, international NGOs such as the Global Slavery Index, rely on their local counterparts, which are financially dependent on these same or similar international organisations. In a roundabout manner, local NGOs also tend to publish the statistics, which they would have first generated, after their release by international organisations had bestowed on them the aura of international credibility. Thus, in order to understand slavery figures one has to understand the objectives of the financiers of local NGOs.

While it is a complex task to trace all foreign donors and to determine their level of investments, some of these groups have earned some notoriety. A good example is the American Anti-Slavery Group (AASG). Since its creation in 1994, the AASG has provided various forms of assistance to a variety of individuals and NGOs working on the issue of slavery in Mauritania. SOS Esclaves, whose unreliable data constitute the background of Global Slavery Index’s 2014 figures, was for a period of time a recipient of AASG’s largess. AASG has also lent support to the former presidential candidate and anti-slavery activist Abeid. But what is AASG?

AASG was founded by Charles Jacob, a man with close ties to the far right in Israel and some Islamophobic American organisations and personalities, such as the American Defense Initiative of Pamela Geller. Jacob has used his public stature and his academic work to instigate uproar against a supposed looming takeover of America by an Islamic tsunami. Both Jacob and Geller have sponsored anti-slavery ads and posts featuring deliberately erroneous facts and figures about Mauritania.

Jacob’s ties to Israel explain his relative silence about Mauritanian slavery issues during the decade between 1999 and 2009 - the period in which Mauritania had an open diplomatic relationship with Israel. They also explain how Jacob uses his campaigns against oppression perpetrated by non-Westerners (which to him mean Arab Muslims) to divert attention from the atrocities committed by Israel and to combat the success of Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement on American university campuses.

Conclusion

Despite the errors and contradictions in NGO and news reports, there are still small pockets of slavery in the country. These exist in areas where governmental institutions have little presence and where their services are almost absent. Ironically, these are also the areas where national and international NGOs, which claim to fight slavery, never go.

This problem has to be addressed. But this is a relatively smaller problem compared to a more pressing issue in this respect. While the country’s slavery problem is not of the scale painted in Western media (especially since the country dissolved its relationship with Israel), the country has a massive slavery-related problem. In addition to the small pockets where slavery is practiced, hundreds of thousands of former slaves and their children are on average poorer and less educated.

Instead of squandering considerable resources to vilify the country and stoke up racial tensions among its various ethnic groups, these international agencies and foreign governments, if truly disinterested, could help, for instance, create programmes of sustainable development within the areas where the most vulnerable (not the most vocal and internationally connected) members of the Haratine live. This must also include real measures to reach out to those segments to ensure that their members are properly educated about, and are engaged in, the management of the programmes the government creates to improve their lives.

[1] Birama O. Abeid is currently imprisoned, in company with other militants, on charges of disturbing the public order for the organising of an unlawful march. This is an odd occurrence given the fact that Abeidi is notoriously known for his inflammatory rhetoric that amounts, for many, to outright racism and was never indicted for that deplorable behaviour. So his latest troubles with the justice system are more likely related to his opposition to the government and thus more political than legal in nature. For instance, his recent statements bestowing praise on public media are in sharp contrast with his public statements, during and before the electoral campaign where obscene racial slurs were commonly used in order to appeal to the most extreme segment of his ethnic base.

[2] L’Eveil Hebdo, no 1015, April 7, 2015

- Ahmed Meiloud is a senior fellow with the Southwest Initiative for the Study of Middle East Conflicts (SISMEC) and a Doctoral candidate at the School of Middle Eastern and North African Studies at the University of Arizona. His research interests include studying the various movements of political Islam across the Arab World, with special focus on the works of the thinkers, jurists and public intellectuals who shape the moderate strands of Islamism

- Mohamed El Mokhtar Sidi Haiba is a social and political analyst, whose research interest is focused on African and Middle Eastern Affairs

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A man walks towards a desert zone that was reforested in front of dunes, 8 June 2002, in the Mauritanian Kiffa region (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.