ANALYSIS: Push for genocide recognition further isolates Turkey

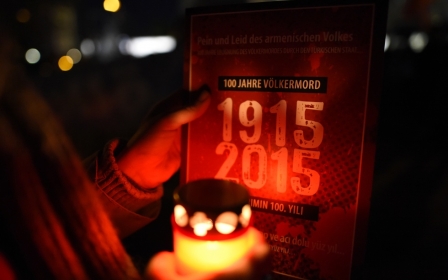

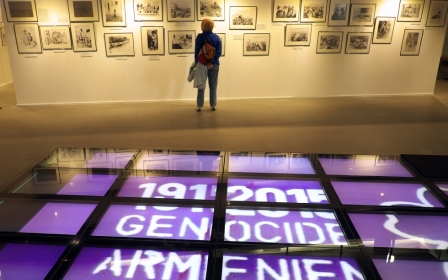

On the centenary of the mass killings and deportation of hundreds of thousands of Armenians in Asia Minor by the late Ottoman administration, calls for recognising the atrocities as genocide is dividing the public opinion both in Turkey and abroad.

Fed up with the constant denial and state language of Turkey, many Turkish citizens are commemorating the 1915 massacres together with many others in different parts of the world.

While Istanbul's Taksim Square is the meeting point for those who gather for the remembrance, the Armenian capital Yerevan, Paris and many other cities around the world that host large Armenian communities have seen commemorations.

Infuriated with the recent genocide recognition of the Pope, the EU parliament and several countries, Turkish officials' rebuttal coincides with another commemoration ceremony, the centenary of the Dardanelles military campaign during World War I.

The Dardanelles events were moved from 25 April to 24-25 April this year, which has been interpreted by some as an attempt to overshadow the 100th anniversary of the Armenian genocide. "It’s not just Gallipoli," said Nazar Buyum, an Armenian columnist and writer at Agos daily.

During the WWI, the allied British and French forces fighting against the Turks tried to cross the Dardanelles strait to capture Constantinople, the capital city of the Ottomans. When the naval campaign has failed earlier in March 1915, they launched an amphibious assault to go by land over Gallipoli.

With soldiers fighting for the British empire from Australia, New Zealand, India as well as Nepal, the operation was not successful and Turks won the battle. For many Turks, the Dardanelles and Gallipoli campaigns have become one of the legendary moments in the country's military history.

To mark the 100th anniversary of the Dardanelles campaign on this very same day, Turkey is hosting an international conference with a high-profile attendance from the belligerents of WWI. But behind this move Buyum suspects an ulterior motive.

"Someone also had the audacity to suggest the organisation of a Gallipoli memorial concert in an Armenian church in Istanbul for 24 April. The government does everything to overshadow the centennial of the genocide this year.”

The G-word

Loaded with a constant reminder of the notion of "crimes against humanity", the G-word and its recognition has become the battleground of today's diplomatic quarrels. For many years, Turkey pushed and sometimes threatened its allies to avoid using of the word, hinting the potential consequences that they could face if they do otherwise.

Although Turkey recognises the extent of the tragedy and the atrocities that the late Ottoman administration committed, the official language does not scale up to the level of genocide. For Turkey, the indiscriminate mass deportation of the Ottoman Armenians from their homes to the deserts of Syria was a wartime measure during the World War I and was not intended to let them perish en masse. This view is highly challenged.

According to Marcus Meckel, the penultimate foreign minister of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), considering the German experience, Turkey should eventually recognise the genocide. But for him, it is not the first step that it should take. "States first start with opening up a space for discussion to find what happened and how was it like during the atrocities," he told Middle East Eye.

Meckel is currently presiding over the German War Graves Commission, an initiative working within the framework of the commemoration and remembrance of both world wars.

For the Armenian side, the recognition of the genocide has become the prerequisite for starting a reconciliation process; but between Turks and Armenians there is almost no middle ground. To overcome the deadlock, Turkey and Armenia initiated a rapprochement process, which started with what was called "football diplomacy" in 2009.

The former Turkish president Abdullah Gul's visit to Yerevan in 2009 to attend a national football game between Armenia and Turkey led to the signing of the Zurich accord. The protocols, which aimed to open the border between the two countries and establish formal relationship, were never approved by the parliaments of each country.

There is a more recent conflict that has put relations between Turkey and independent Armenia into a semi deep freeze. The Nagorno-Karabakh war between Azerbaijan and Armenia in the last years of the Soviet Union, and Turkey's siding with Azerbaijan has become another obstacle to reconciliation. The border has been closed since 1993.

Turkish perspective

Due to the Soviet occupation of Armenia for most of the 20th century and the relative lack of public attention to the Armenian genocide during that period, the commemoration of the atrocities and the occasional demands for its recognition is a rising phenomenon of the last few decades.

For most of the last century, a culture of denial in Turkey, reinforced with state school curricula, dominated the minds of Turkish citizens. The lack of a critical approach to the issue with different perspectives as well as the prevailing nationalist ideology in Turkey has prevented the opening of discussion channels even at the national level.

Halil Berktay, a Turkish historian at Sabanci University calls this state mantra "The theory of the immaculate conception of the Turkish Republic." According to this view, Turks and the Turkish state are infallible, and that is the reason why a genocide could not have taken place.

This way of thinking has been repeated by various officials on different occasions, the latest example being last week when the former deputy prime minister, Emrullah Isler, insisted that genocide as a concept that could be only committed by Europeans. He said: "There is no genocide in our culture, our traditions, and our history. There is tolerance, compassion, and love. […] If there is genocide, it is the Armenians who have committed it."

It was not until 2005 that the events of 1915 could be discussed in Turkish academia. A conference held that year - amid massive threats to its organisation - was the first of its kind in Turkey to bring about different perspectives from different countries.

The milestone development paved the way to a more open discussion environment, helping many historians, especially those who are not in line with the official Turkish discourse, to contribute with heterodox approaches on the issue.

A reminder of the intolerance in some quarters toward those who question the national myth came with killing of Hrant Dink in 2007 by a Turkish ultra-nationalist. Dink was a renowned Turkish-Armenian journalist and the editor-in-chief of Turkey's notable bilingual newspaper Agos.

However, this sorrowful development sparked a massive outpouring fromTurkish society, with calls for a different approach and mentality toward the past. Hundreds of thousands of people attended Dink's funeral, carrying placards that read: “We are all Hrant, we are all Armenians.” Since then the anniversary of his death has become a commemoration day for many Turkish citizens.

Turkish government on the defensive

The reactions to the assassination of Dink and the Turkish government's attempts to normalise relations with Armenia in the aftermath was largely received as a positive development in different parts of the word.

Although the issue of recognition on the eve of each 24 April anniversary has occupied the minds foreign ministry officials in Ankara, the stumbling block of parliamentary approval of the Zurich accord in both countries prevailed.

When it became clear that the protocols would not be signed anytime soon, Turkey again came under pressure to make conciliatory moves over the 24 April commemorations. The prime minister of the day, Recep Tayyip Erdogan's condolences to Armenia last year, repeated by Ahmet Davutoglu this year, were positive steps, but the increasing pressure from the international community is putting the government on the defensive.

For some, parliamentary recognition of the genocide is a tool to push Turkey in the right direction for an eventual admittance of its role in this crime against humanity. However, for many others, these attempts are only pushing Turkey to be even more on the defensive, potentially closing all the doors for a possible reconciliation.

Dink paid the price of calling the atrocities a genocide with his life. But he was a perfect observer of both views. He suggested that genocide took place and he never refrained from using this word. But he was also aware that the emotive power of the word has overshadowed Turkish-Armenian reconciliation.

Long-time Caucasus observer Thomas de Waal recalls Dink's efforts with the Turkish reality: "[Dink] criticised genocide resolutions in foreign parliaments on the grounds that they merely replicated previous great-power bullying of Turkey. He saw his mission as helping Turks to understand Armenians and the trauma they passed down over generations, while helping Armenians recognise the sensitivities and legitimate interests of the Turks."

On the eve of the upcoming June elections, calls to Turkey to recognise the genocide and parliamentary resolutions in various countries brought three otherwise hostile parties together to make a joint parliamentary declaration. With the exception of mainly Kurdish, People's Democratic Party, all three main political parties in the parliament forgot about their national quarrel and joined each other to condemn the EU parliament’s genocide resolution.

In other words, although positive developments in Turkey over the past decade have taken root at the societal level, the increasingly dismissive attitude of Turkish officials in the face of outside pressure has pushed the country further away from reconciliation with Armenia. Considering the upcoming elections and the attitude of the three main political parties in the country, there is little prospect of this impasse shifting any time soon.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.