IS claims to break open Syria's notorious Tadmor Prison

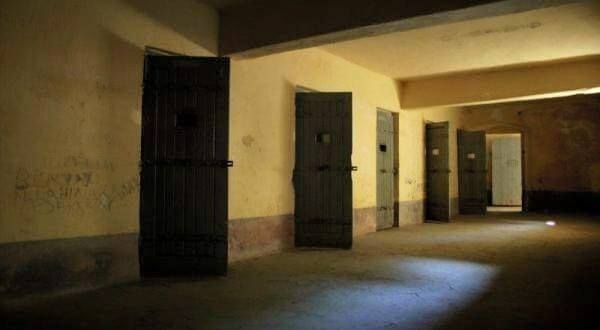

Supporters of Islamic State (IS) on Thursday circulated old images of Syria’s notorious Tadmor Prison, claiming that they had thrown open the facility’s doors.

The images, which date back to at least 2008, were posted online by IS supporters the day after the group claimed to have seized control of the modern city of Tadmor in the western Homs province.

Attention has been focused on widespread fears that IS will raze the UNESCO World Heritage site just south of the modern town - but the claimed capture of the prison could actually be a much more significant development, according to analysts.

Originally built by the French during their decades-long mandate, the prison came to represent for many Syrians the violence of successive crackdowns on dissent, and could now have wide-reaching propaganda value.

Fear of reprisals

Though the spotlight is on the Palmyra ruins, which date back to the first century BC, many also fear that residents of the modern town of Tadmor could now be at risk.

Images appeared on Thursday claiming to show the dismembered bodies of Tadmor residents from the Shaitat tribe, which rebelled against IS in December 2014 but was crushed in what is thought to be the bloodiest massacre committed by the group in Syria.

Such apparent reprisals, analysts say, could become a common sight in a town that has been under government control throughout most of the more than four-year civil war.

“Anyone suspected of working with the regime will be killed,” according to Faysal Itani, a resident fellow at the Atlantic Council in Washington.

“Anyone who acquiesced to regime rule but did not actively participate in the war effort will be given a chance to repent and pledge allegiance to [IS leader Abu Bakr] al-Baghdadi.”

IS's lightning advance came after President Assad's overstretched forces withdrew from the area. With the fall Tadmor, IS is now said to be in control of 50 percent of Syrian territory.

Within Syria, the area overrun by IS on Wednesday is known as much for its ancient ruins, which used to attract thousands of tourists a year, as for the infamous Tadmor prison in the modern town.

“Tadmor is a symbol of oppression, torture and the dark days of the 1980s,” says Nadim Houry, the director of Human Rights Watch’s Beirut office who has investigated Syria’s detention centres and interviewed former detainees.

“It came to symbolise the brutality and cruelty of the crackdown in the 1980s.”

In 1980, the prison was the scene of a massacre committed by forces under Rifaat al-Assad, brother of then-president Hafez al-Assad.

In June of that year members of Syria’s Muslim Brotherhood attempted to assassinate the Hafez al-Assad, whose son would follow in his footsteps to become president of Syria.

The next day, soldiers went from cell to cell in the prison, eventually killing an estimated 1,000 prisoners.

The massacre of 1980 is now well documented. However, says Houry, little is known about what else went on at the facility, with reports that unknown numbers of prisoners who died of disease there were simply buried in unmarked graves in the desert region.

“Like many of these prisons that have come to personify cruel regimes, it holds a lot of secrets. It will be much harder for any of these to come out now that IS is in control [of the area].”

Tadmor prison was closed down in 2001 when Bashar al-Assad took over from his father, in a move many hoped would mean reforms and an end to widespread torture in Syria’s prisons.

A decade later it was reported that the prison had been reopened to house anti-government protesters who took to the streets in the early days of the uprising against Assad’s iron-fisted rule.

Though the reopening of the facility has never been fully documented, local activists in Tadmor said on Wednesday that the prison housed thousands of detainees, large numbers of whom had been transferred to an army base to be given weapons and forced to fight against IS.

While little is known about the identity of prisoners at Tadmor, the Atlantic Council's Itani says it is a key strategic site for IS, and could be far more important than the unique ruins nearby.

“IS has no interest in ruins, apart from the inflammatory effect that capturing them seems to have on international public opinion,” he told MEE.

“They seem to enjoy taunting and provoking the world, and this seems to work well with ruins.”

From a military perspective, Tadmor prison is a more important goal. Itani suspects there are “at least some” militants detained there, who would be potential new recruits if freed by IS.

“The intended capture of an important regime asset fits within a larger motive to capture and control Tadmor,” said Itani.

'Potent' symbolism of Tadmor prison

More important than its strategic importance, though, is Tadmor's resonance as a symbol of the repression Syria suffered under two successive Assad presidencies.

During the IS advance on Tadmor, the group’s supporters promised to “liberate” detainees who they said had been languishing there for years.

Translation: Tadmor prison is home to at least 13,000 prisoners, some of whom have been inside for decades

The West and the militias do not care about them…they just bark about the ruins! #CaliphateState

“Tadmur prison is a potent symbol of regime power and oppression,’ says Itani. “Its capture is an equally potent symbol of regime impotence and, by implication, IS power.”

For Houry, the advance on Tadmor prison illustrates the double bind that many Syrians have found themselves in since the fracturing of the opposition and the rise of IS.

“In another context the capture of Tadmor prison would have been cause for celebration,” he told MEE.

“The fact that it has fallen into the hands of another cruel group encapsulates the Syrian tragedy today. Syrians are stuck either between the cruelty of the Assad regime and that of IS.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.