The non-states of the Middle East: A new era

At dawn on Thursday, the Islamic State (IS) launched a surprise attack on the predominantly Kurdish town of Kobane, on the Syrian-Turkish border. The attack started with twin car bombs, which were instantly and exclusively covered by the Turkish state media agency, Anadolu.

Practically speaking, either IS managed to provide the Turkish agency with live coverage, or the agency’s reporter happened to be roaming around the streets of Kobane at dawn.

Also, the twin car bombs exploded close to the crossing point with the Turkish town of Mursitpinar, and Kurdish activists and residents claimed that the attackers had come across the border, despite it being heavily policed on the Turkish side.

This incident, and the allegations of Turkish complicity, reflect a wider reality that emerged after the revolts in the Middle East. Non-state actors are shaping battles and states are yielding.

Proxies and autonomies

It became clear to the Iraqi government that their US-trained army cannot push IS back. The Iraqi Popular Mobilisation Forces (known as Ha’ash al-Shaabi) proved to be pivotal in the battle against the group.

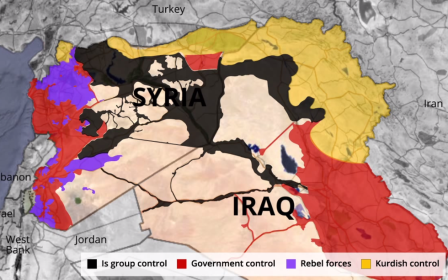

On the Syrian front, the regime forces, drained in years of fighting, are incompetent. Instead, the Syrian regime is being backed by the Lebanese Shia militant party, Hezbollah, and other militias supplied by Iran. The Kurdish forces, on the other hand, have changed the course of events by winning consecutive strategic victories against IS.

This means that the future of the region is being shaped by non-state groups who are on the frontline. By shaping the future, non-state groups don’t necessarily gain state-like autonomy or institutional power. It is more likely that the successes of non-state groups will only help decide on which regional power triumphs in the future and where.

But, if non-state groups are shaping the battles, and thus the future, why is it that the future belongs to regional powers – i.e. states? The question can only be answered by understanding the contingent politics between states and non-states.

Non-state groups in the Middle East are not operating outside the political economy of states. The flow of war capital essentially happens through state-run systems. During times of war, black markets and private war businesses are kept at the margins of the war economy, unless they are indirectly active under the consent of state intelligence services. Multi-billion arms deals are sealed by governments. The cost of war is incurred by governments, more so in the Middle East.

Consequently, non-state groups rely heavily on state sponsorship and support. This support comes as a form of rent, whereby non-state groups operate on the ground in a way that advances the interests of their state sponsors. This role, defined as a proxy role, is prevalent in the post-Arab Spring era.

But the extent to which non-state groups compromise their autonomy for a proxy role varies from one group to another, and from one context to another. However, generally, non-state groups still entertain varying levels of autonomy, thanks to the fact that states need them.

The era of non-states

The series of revolts in the Arab world was radical, and thus counter-revolutions had to be equally radical to contain them. Under this understanding of revolutionary dynamics, several non-state groups emerged to co-opt mass mobilisation and pave the way for regional contests to be internalised.

In other words, the legitimacy crisis faced by states in the region was compromised by non-state legitimacies: the Jordanian king relies on tribal allegiance; the Syrian regime, as well as the Iraqi, rely on sectarian non-state mobilisation and organisation; the Lebanese regime relies on sectarian parties; Gulf monarchies rely on proxies in Syria and elsewhere.

The fact that states need non-state proxies more than ever allows those proxies to have some bargaining power over political agendas and processes. Some non-state groups play on regional state rivalries to advance their interests. In that context, the dynamic relationships between states and non-states are shaped.

The Islamic State or the non-state state

Given the geographic size of the political constellation, from Libya to Iraq, it becomes increasingly difficult for states to control the ground, leaving behind an imminent risk of non-state groups defying state-sponsored “organised chaos”.

In that sense, IS emerged as an anti-establishment group that claims to pursue the destruction of all standing regimes in the region. This role is being well-played and has brought state rivals together. On Thursday, Putin called Obama to discuss better collaboration in the war on IS. To do so, Kerry and Lavrov are expected to meet soon. For the same cause, Shia militia members who were raised chanting “death to America” are now sharing a base with US troops in Iraq and the Islamic Republic of Iran is rushing to draft a nuclear deal with “the devil”.

It is when IS, as a non-state group, managed to establish political, economic and social structures that are largely independent from the structures of the Syrian and Iraqi states that it became capable of deconstructing our understanding of a state. In doing so, questions arise as to how far states can keep non-state actors dependent, and when non-state groups see their interests served best without state sponsors.

The grassroots alternatives

As non-state groups become incorporated in the regional status quo, the interests of Arab societies and the demands raised in the Arab revolts will be further marginalised. To break the deadlock, the Arab peoples must improvise organic initiatives to organise and delegitimise proxy wars and regional rivalries.

The readiness of states and non-state groups to coerce such efforts add to the difficulties faced by activists and revolutionaries across the region.

- Ibrahim Halawi is a London-based researcher and a PhD candidate at Royal Holloway University of London. His research focuses on power dynamics and counter-revolution in the Arab World. He has published contributions on Political Islam in the context of the Arab Spring and the geopoliticial challenges to secularism in the Arab World. Also, he founded a secular student-run newspaper in Lebanon.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: File photo of Islamic State fighters

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.