The History Tapestry Project: Narrating the story of Palestine through art

After the abolition of Apartheid in South Africa, the Keiskamma History Tapestry was created in the tradition of the famous Bayeux Tapestry to tell the story of South Africa’s Xhosa people and the turbulent history of the Cape frontier region and South Africa. The 126-metre-long tapestry was embroidered by village women from the Eastern Cape and now hangs in the South African parliament.

Jan Chalmers was one of two British women who taught embroidery to South African village women, helping them to create the Keiskamma tapestry.

Having visited Palestine frequently and spent two years working in a health centre run by the UN agency for Palestine refugees (UNRWA) along with her husband, Chalmers had a long-standing interest in Palestine and its people. It’s this admiration that inspired her to start the Palestinian History Tapestry project.

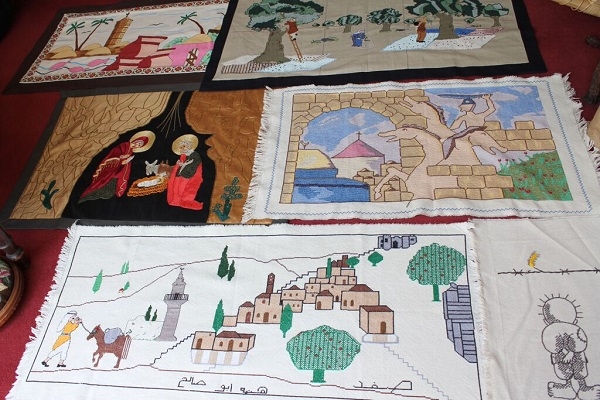

The project aims to tell the story of the Palestinian people and preserve the heritage of their ancestors and forebears through the use of traditional Palestinian cross-stitch embroidery, done by Palestinian women in the occupied territories and refugee camps in the diaspora.

“I spoke to my friends Helen Hawari and Judith English, and they were both very keen to join the project. Soon after, I went out with Helen to the West Bank and Jerusalem to talk to the Palestinian women there and see what they thought,” Chalmers told Middle East Eye. “They were all up for it and that’s when we had the first three panels made.”

The idea was to create one-metre-long embroidered story panels that could all be stitched together. Each panel would be separated by a spacer (smaller embroidered panel), and once complete the panels would combine to become the Palestinian History Tapestry.

The nativity scene panel was stitched in Beit Jala near Bethlehem on raw silk using the ancient Tahriri (couching) method of stitching, which is unique to Bethlehem. The second panel was a depiction of the seasonal olive harvest and was stitched in Balata Refugee Camp in Nablus.

A number of panels were also made in Gaza, including the Gaza fishermen panel, Gaza rooftops, and an Arabic calligraphy panel which reads “We have on this land that which makes life worth living," a quote from a poem by the famous Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish.

Folkloric panels and spacers were then made illustrating Palestinian heritage and culture, such as the traditional Palestinian wedding panel, the henna party panel, and traditional Palestinian dresses.

Other panels reflected life under Israeli occupation and carried symbols of defiance, such as the Land Day panel, the Handala spacer, and the Steadfast spacer, which was stitched by Samar Alhallaq in solidarity with female Palestinian detainees in Israeli jails. She worked on the tapestry shortly before she was killed in an Israeli airstrike in Gaza last summer along with her two sons and unborn baby.

“The war on Gaza put a big depression on the project. We lost Samar and everything came to a halt,” Chalmers said. “But Hasan, Samar’s husband, very much wanted the work to continue, and just like a phoenix rising from the ashes, the women started working on the panels again.”

Threads of identity

Palestinian embroidery has been the traditional handicraft of Palestinian women for centuries. It was passed down from generation to generation and was primarily manifest in the beautiful and skilfully embroidered clothing worn by local women. The design, stitching method and colours often reveal the wearer’s status and place of origin within historic Palestine.

Since the Nakba of 1948 and the creation of the state of Israel, Palestinian embroidery has taken on even more meaning and is seen as a symbol of Palestinian culture, and a valuable way of keeping Palestinian identity and heritage alive.

Its significance also stems from its various motifs and pattern designs that help to show off the diverse history of the land and its inhabitants and date back as far back as the Canaanites, who lived in the region some 4,000 years ago.

Many of those designs bear names that evoke various periods in Palestine’s history, such as the Canaanite star and Pasha's tent.

Palestinian author and academic Ghada Karmi, whose family fled Palestine in 1948, has been a patron of the project and is currently acting as a historical advisor to the UK team.

Karmi says she was was initially drawn to the project because of its celebration of Palestinian women and culture. However, over time Karmi became more interested in the project for its historical significance and rebuttal of the Zionist and Israeli narrative that lays claim to the land.

“Palestine is an ancient land and the people of Palestine, of course, changed over time, as there were invasions and colonial and imperial rulers. Some of those people became Jewish, some converted to Christianity, and many eventually converted to Islam and stayed on the land,” she said.

The next round of panels to be embroidered will embrace a wider span of history. The tapestry’s first panel will be characteristic of the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic period, moving on to other periods, including the Stone, Bronze and Iron ages and then to periods of Roman, Byzantine and later Islamic rule, first through the Mamluk Sultanate and then the Ottomans.

It ends with the modern history of Palestine and the formation of the Israeli state and subsequent dispersal and occupation, while also shedding light on the historical Jewish presence as well.

“The message,” Karmi said, “is that there had been a continuity of the land and the people of that land until 1948 when something unprecedented in the history of Palestine happened, which is instead of the new invaders coming in with their particular ideas or style of living, for the first time they took the place of the indigenous population.”

Chalmers said she believes everyone will interpret the tapestry differently, but she also hopes that it will inspire people and make them think about how much they underestimated less well-known parts of the land's history.

Shayma al-Waheidi is a student from Gaza currently studying for a master’s degree at Oxford Brookes University in the UK. She is advising the project’s UK team, but on her return to Gaza she plans to become coordinator for the project’s Gaza branch.

“The importance of the project springs from its beautiful skilled artwork, cross-stitch embroidery and its preservation of the history of Palestine,” she told MEE. “Hopefully, it will be able to bring Palestine’s millennia-long heritage to light.”

A positive reception

The project’s treasurer, Judith English, has not had the long-term contact with Palestine that Chalmers and Hawari - who all founded the project together - have had. A newcomer to Palestinian issues, English started reading about the situation when her husband Sir Terence English, a cardiac surgeon, began visiting Gaza on medical trips.

“I was drawn to the idea of a Palestinian tapestry and I particularly thought that supporting other women was good,” English told MEE. “I very much had the feeling that involvement in creative activity, like textile art, can be a valuable way of sustaining hope and helping the women to have a sense of self-esteem as well.”

English said she is learning a lot about Palestine through the project, and she is currently taking the lead on fundraising opportunities and helping out with the project’s local events in Oxford, such as the annual Christmas Bazaar where they sell Palestinian products and embroidery to fundraise and compensate the embroiderers.

“It is certainly a project funded through smaller donations,” English said. “It has appealed to a wide range of people, and quite a lot of people have been giving small amounts of money.”

Sara Chaudhry is a young Brit who first became aware of the tapestry project during her undergraduate study at Oxford Brookes University, where she became friends with Palestinian students involved in the project.

“One of the main things that I love about the project is that Palestinian women are using art as a means to reclaim and share their history, but also to ensure that it is not lost,” she said.

Having attended an exhibition for the project at St Giles Church in Oxford last month, where photographic reproductions of all the current embroidered panels and spacers are on display, Chaudhry said she believes the general perception of the tapestry project has been very positive.

Chalmers hopes the tapestry will ultimately be hung up in the Palestinian parliament after it is finished. But the region’s divisions might make this impossible and she says she fears that the tapestry will be attacked or destroyed once it is on display.

Should her fears come to pass, it will be just the latest instance in what has been a long line of theft and attacks perpetrated against Palestinian culture and identity.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.