Former Palestinian hunger-strikers speak out

BETHLEHEM, West Bank - Walid Gharrfa deals with intense stomach pain almost daily. He says it’s a residual effect of the 45-day hunger strike he went through in Israeli prison that left him with serious stomach damage.

Gharrfa, now 22, was only 17 years old when he was sentenced to three years in prison for his political activism in the West Bank.

It was just a few months into his sentence that he started the hunger strike, along with his prison mates, in protest against the prison guards’ cruel treatment of family members during visitation days.

“I remember every stage of my strike. The first week we just drank water and salt, and no one moved,” Gharrfa told Middle East Eye, a grimace on his face as he recalled the memory. “We all stayed in our beds without moving an inch.”

While doctors told Gharrfa that the lasting affects of his hunger strike would require surgery, the procedure he needs is not offered in the West Bank, and his family cannot afford to send him abroad. Without it, the agonising pain is set to continue quite possibly for life.

But Gharrfa is used to pain. During the 45-day strike, the dark-eyed youth who looks much older than his age says that he felt like he was dying.

“I was killing myself,” Gharrfa told MEE, rubbing a calloused hand across his abdomen. “I knew that my body was telling me that every step of the strike. My mind was fine. I knew what I was doing was important, but I also knew my body was shutting down and if I kept going, for sure any person who doesn’t eat will eventually die.”

For decades, hunger strikes have been carried out by Palestinian prisoners throughout Israeli prison systems. This tool can be employed by individuals, groups of hundreds and sometimes even thousands of people at one time. The consequences can be devastating and many who go without food for prolonged periods of time face life-long medical complications and ultimately death. For those who endure, however, the rewards can be great.

On Sunday, Khader Adnan, an Islamic Jihad activist, captured world headlines when Israeli authorities decided to release him following a 55-day hunger strike more than a year after he was first arrested and subsequently held without charge. Back in 2013, Samer al-Issawi also secured his release 15 years early after going on a record-breaking 266-day hunger strike during which time he subsisted on water and vitamin shots.

According to Dr Osama Salah, a physician from Ramallah and member of the American Society for Nutrition who has treated former hunger strikers, the preparation for a long-term hunger strike is critical in helping to avoid long-term effects like those experienced by Gharrfa and many others.

“They have to prepare themselves a couple of weeks before they start by eating certain proteins and making their diets smaller in a way to prepare their body for the situation of not eating,” Salah told MEE. “The hunger strike is a prisoner’s last means of protesting, and it’s very dangerous, it's not a light decision to make.”

According to Salah, taking the proper steps before, during and after a hunger strike can make the difference between recovery and serious long-term effects. Hunger strikes lasting more than 30 days however, are likely to cause permanent damage regardless of the measures taken, he said.

Even though Gharrfa says he didn’t follow every rule “by the book,” like preparing for the strike weeks before as Salah recommended, he did take safety measures, like being very still during the beginning of the strike and listening to advice of older prisoners.

His 45-day strike simply went well beyond the point where someone could expect to avoid enduring physical repercussions.

He was young, and the strike was open-ended – he had no idea it would go on for so long. In the end though, he says that his family and other visitors were granted better treatment and were allowed greater visitation rights.

“The second week [the Israeli guards] started taking us out separately, trying to make us eat, putting food in front of our faces to tempt us to break our strike, telling us they wouldn’t tell anyone,” Gharrfa told MEE. “This is the occupation: they want to break our feeling and our strength, but we knew that so it was easy to say no even though we were starving.”

Gharrfa knew better than to take the offered food. First, being in solidarity with his fellow prisoners was a stronger pull than any hunger pains, and second, he knew eating a regular meal two weeks into the strike would cause more pain and damage than relief.

According to Salah, the practice of tempting someone on a hunger strike to eat is very dangerous.

“Going back to eating regular meals is more dangerous than the strike itself,” Salah told MEE. “They have to go on gradual steps. It takes a few weeks before they should eat a regular meal again. By being forced to eat food through a tube or even tempted with a big meal, they can cause horrible damage - internal bleeding even. If the prisoners are served a real meal and they don’t have good knowledge on the proper ways to break their strike slowly, it is very dangerous.”

While prison guards often try to lure prisoners to break the fast even in medically harmful ways, many hunger strikers manage to gain invaluable advice from older prisoners who have often gone on multiple hunger strikes during their time behind bars.

In Gharrfa’s case, veteran prisoners Khalid Azrak, 50, was on hand to teach the younger inmates how to successfully carry out a strike.

Older generation

The first wall of Azrak’s living room in his modest house in Aida Refugee Camp is lined with plaques and trophies, but he is no competitor. Azrak has spent most of his life in Israeli prisons - the awards are all gifts of appreciation from various organisations, thanking him in one way or another for the sacrifices he made for his country.

During Azrak’s long stay in prison, he became a fountain of wisdom about all things resistance, and he says, like the rest in his age group, he continues to do his best to pass on as much of this unique knowledge as he can.

“We made sure the younger ones knew exactly what they were doing,” Azrak told MEE.

“If we had already started a hunger strike and a new prisoner came in we didn’t let them start with us. They needed to really understand what they were striking for, the young ones especially;, they needed to understand what it means to hunger strike mentally and physically.”

Starting in his teens, until only a year ago, Azrak served four nonconsecutive terms in Israeli prisons, the longest and most recent of which lasted 25 years. During that period, he committed himself to long-term hunger strikes four times, and smaller less consequential strikes more than he can count.

To Azrak, a clean cut man with a quiet demeanor, the hunger strike is a Palestinian prisoner’s most useful tool.

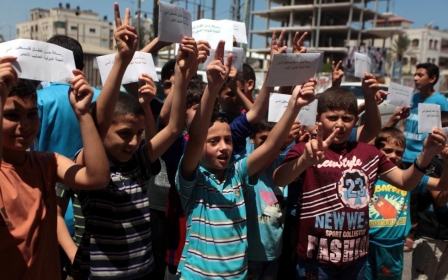

“The power we hold inside the prison during our hunger strikes is only useful because of our Palestinian brothers outside,” Azrak said. “Israel knows that if one of us hunger strikes and we die, the community outside the prison will protest - they won’t let us die quietly. Israel is scared of that, we know this.”

Over the years Palestinian prisoners have garnered headlines again and again with photos of shrunken men’s gaunt cheeks and bulging eyes, literally withering away for their cause.

Last year, 63 prisoners committed to a two-month-long hunger strike in protest at Israel’s policy of administrative detention, a policy that allows prisoners to be held indefinitely, and without trial, with no explanation.

While there are cases of mass hunger strikes that make the news, or famous individuals who take on long-term strikes such as Khader Adnan’s recent 55- day strike, Azrak said the hunger strike is more widely used in Israeli prisons than most would think.

“Of course we made long-term hunger strikes for big issues, but in the prison we would hunger strike for just a few days at a time, several times a month for smaller issues, like demanding longer family visits, or being allowed writing material,” Azrak said. “No one hears about those.”

“I don’t regret any of my fight for Palestine, and I would do a hunger strike again. There isn’t really another tool as strong as the hunger strike for us in prison. The hunger strike is powerful, and we’ve seen again and again that it works.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.