Algeria's Ghardaia: Old brothers, now enemies

Except for a few carpets and mattresses rescued from the fire, a forehead injury that is only protected by a makeshift bandage along with a splint that holds the little finger of his right hand, Ammar has nothing left. But at least he is alive.

“The attack began just after dawn prayers, around 4am. We heard cries and went up on the terrace. The house was surrounded by men whose faces were obscured by an Arabic scarf [headscarf worn by men in the Sahara], armed with iron bars and knives. We negotiated to have the women evacuated. They jumped over the courtyard wall; we were beaten and Molotov cocktails were thrown at our house, which was completely burned," Ammar said.

"In the fight, one man lost his scarf," he said. "And then I recognised him. He was my neighbour.”

Fifteen days after 23 people died in clashes between the Mozabites (Berbers who follow the Ibadi Muslim rite) and Arabic-speaking Muslims of the Maliki tribe (a branch of Sunni Islam), tensions have escalated in el-Guerrara, a town of 75,000 inhabitants located 100km away from the Sahara desert city of Ghardaia.

Violence is not new in this area. The first clashes between the two communities date back to 1975, but the conflict has picked up in both intensity and frequency since 2013. This summer, the death toll in al-Guerrara exceeded that of 2013 for the entire valley.

Under a blazing July sun - where the temperature can rise up to 45 degrees Celsius at noon - children play in the courtyard within a centre for victims of violence. The Mozabite community has taken care of hundreds of families who fled the violence, like Ammar’s, and distributed them in four schools across the city.

"We brought in a psychologist for children because they were traumatised by what they saw," the centre’s manager Abdelhamid told Middle East Eye.

Highlighting the fact that Mozabites have "not waited for help from the state to act," he shows a board where the list of families and the regulations of the makeshift camp have been plastered.

In classrooms, the children’s drawings and conjugation tables remained displayed on the walls, propped against cardboard boxes and furniture blackened by the flames pile up. The burning smell is still very present.

Opposing stories

In the Larbi Ben M'hidi district, inhabited mostly by the Arab-speaking population, men come out of the mosque and gather to talk. Ben Barek el-Hajj, an Atatcha Arab tribe notable, opens an iron door in an empty street. This is where 25-year-old Bashir Messaoud was killed just days before his wedding.

Nothing is left of the house except shattered walls, fingerprints on the soot covering the earthenware, and a burned bag of dates turned upside down. On the front, “Amazigh out!” is written with chalk.

There might be as many versions of the attack as there are stories about the history of both communities. Critically, each side claims the right to live in the area.

Responding to the Mozabites who say they were first to inhabit the valley, Bengrid al-Bouti, a member of Maliki Council, who is considered a moderate, said that his Atatcha tribe (Arabic speaking), has been residing in the valley for centuries and that the first Ibadi mosque "was built on the house of Ben Aissa Atach, founder of al-Guerrara".

Responding to the Malikis, who accuse the Mozabites of being "harkis," or war parties and collaborators with the French army during the war of liberation, Ahmed Bensalah, an elder from el-Guerrara, recalls that the poet Moufdi Zakaria, author of the national Algerian hymn, is a Mozabite.

"The problem is not in the Ghardaia community and even less about religion," said a Socialist Forces Front activist, an Berber opposition party deeply rooted in the region.

"Mozabites and Chaambas [the largest Arabic-speaking population] are primarily hostages of the state who provided no national narrative, leaving, for 50 years, each side building its own narrative against the other."

Inadequate policies

The problem perhaps has to do with the landscape. On both sides of National Road 1, the mythical Trans-Saharan highway linking Algiers to Tamanrasset, new dormitory towns have grown up in the desert, challenging the heat and sandstorms.

One of those towns is Oued Nechou, located about 20km from Ghardaia. It does not meet any urban planning guidelines. Space is tight and cohabitation between Chambaas and Mozabites has proved difficult, evidenced by regular insults or stone throwing.

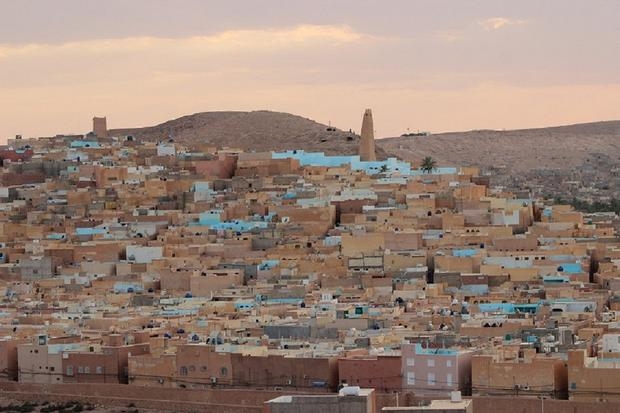

From the top of the rocky hill overlooking Ghardaia, a city recognised for its award-winning urban engineering, Ahmed Nouh sees unplanned urban sprawl as the root cause of the tension between the two communities.

"While Mzab Valley was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1982, it should have been protected, but the state did nothing to curb pressure on the valley!” he protested to MEE.

"Ghardaia holds the record of... the most densely populated area of Algeria. In the city centre, traffic jams look like those of the capital. Do you find it normal while we're in the heart of the Sahara?"

A former state representative from Ghardaia, contacted by MEE, is convinced that the Mozabites "are paying the price of a policy led by Algiers since 1962,” and that the situation in Ghardaia should have been viewed in the context of all conflicts between Tuareg (Berber nomads of the Sahara) and Arabs in southern Algeria, a situation presented instead as inter-community clashes.

"The Tuareg and Mozabites are the only ones who have opposed the division of Algeria as desired by France in the 1950s. Yet they have always been fought. Algiers has never hidden its desire to destroy traditional institutions," the former state representative said.

The state decided to treat the Ghardaia issue as a security problem. According to a source in the intelligence services, nearly 8,000 policemen have been deployed. The military is hardly visible except in nearby hills, where its trucks are parked. Policemen, however, are omnipresent at every junction and roundabout in the city.

Exasperated by the heat and the situation in which they have lived through for a year and a half, they maintain tense relations with the population, especially with the Mozabites, who accuse the police of siding with the Chaambas.

'Learning again to live together'

Mohamed, an entrepreneur in the region and part of the former political party, the National Liberation Front, laments the turn of events. In his modest office, an old election poster of Abdelaziz Bouteflika hangs on a wall with a slogan that says “for a strong and serene Algeria”. On another wall is a quote from Saddam Hussein: “If we can not find common values, remain at least committed to the value of honour.”

"Instead of finding out who was there first, we should learn again to live together as we have always done. Otherwise the region is going to burn,” Mohamed warned.

Ouahab, a Ghardaia trader from Setif, has trouble believing in the power of this kind of goodwill. "Unfortunately, nowadays, young people are less and less influenced by the notables and are more receptive to provocations made by Mozabite extremists and excited Salafists who call for jihad on social media networks," he said.

"I understand that we hold the state responsible for this chaos. However, who else but the state is able to mediate reconciliation efforts between the two parties?”

Note: This article has been translated from MEE's French website by Ali Saad.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.