New Parliamentary elections place Turkey at a crossroads

Nearly three months after the elections on 7 June, Turkish President Tayyib Recep Erdogan announced that the country had no alternative but to return to the ballot box. To avoid prolonging the agony, the Supreme Elections Committee set the date for a new round of parliamentary elections in early November.

Turkey has been ruled for 13 years by the conservative and Islamist-oriented Justice and Development Party (AKP) on the back of comfortable parliamentary majorities in three successive terms. Although the party's first term in government from 2002 to 2007 was marked by a fierce conflict with the army leadership and with the judiciary, the party succeeded in achieving the political stability necessary for making substantial economic progress and in bolstering Turkey’s place as a regional power.

However, last June's elections delivered a result few had expected. The AKP lost its parliamentary majority and the ghost of coalition government returned along with it the memory of political instability. And yet, the main political parties represented in parliament failed to agree on forming a coalition government with an agenda that could be backed by a parliamentary majority.

The AKP was still the biggest party. It won 41 percent of the votes in the last round, securing 258 of the parliamentary seats, only 18 short of an absolute majority. It was clear that the agreement between the AKP and any of the other three parties represented in parliament would yield a coalition government that enjoys a comfortable majority (the People's Republican Party gained 132 seats while the Turkish Nationalist Movement's Party and the Kurdish People’s Democratic Party gained 80 seats each).

Two of the parties were ruled out of a coalition. The Turkish Nationalist Movement Party, which shares with the AKP a tangible segment of its popular base, refused from the start to join any discussion over forming a coalition government, whether with the AKP or anyone else. Nor could the AKP form a coalition with the People’s Democratic Party, because of its close connections with the Kurdish Workers Party (PKK).

So the practical choice came down to a coalition between the AKP and the People’s Republican Party, which as the bearer of the banner of Ataturkism and the republic’s secular heritage, represented the AKP’s political and ideological foe. Although a serious attempt at negotiations was made between the two parties, and the talks themselves went on for several weeks, it was obvious that a deep gulf separated the two parties on foreign policy - over whether or not Turkey should play a role in the Middle East - as well as on the system of education in the country. In the end, talks failed.

This is the first time in the history of the republic, since it became politically pluralist, that Turkey is forced to head towards snap elections over the failure to form a coalition government. The constitution decrees that in the interim, the country should be ruled by a caretaker government in which parliamentary parties participate depending on the respective weights each of them carries inside parliament. The portfolios of justice, interior affairs, foreign affairs and transport are however to be run by independents or technocrats.

Surprisingly, both the People's Republication Party and the Nationalist Movement Party refused to take part in the caretaker government that Dr Ahmet Davutoglu, leader of the AKP, was instructed to form. The two parties reckoned that restricting the caretaker government to cabinet ministers from the AKP and the People’s Democratic Party, at a time when the war is raging once again between the Turkish state and PKK militants, would embarrass the AKP in the eyes of Turkish electorate.

But there were splits. Togrul Turkish, the MP from the Nationalist Movement Party and son of the legendary founder of the party, broke ranks to join the caretaker government. In addition, Davutoglu gave a ministerial portfolio to the former leader of the Grand Unity Party, who represents another wing within Turkish nationalism. With the formation of the caretaker government, the country passes through another phase in the agenda of the transitional period and does indeed enter into the early elections mode. Yet, the question that lurks on Turkey's political horizon is whether a new set of elections will deliver stability and certainty.

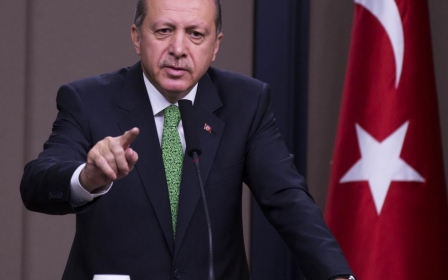

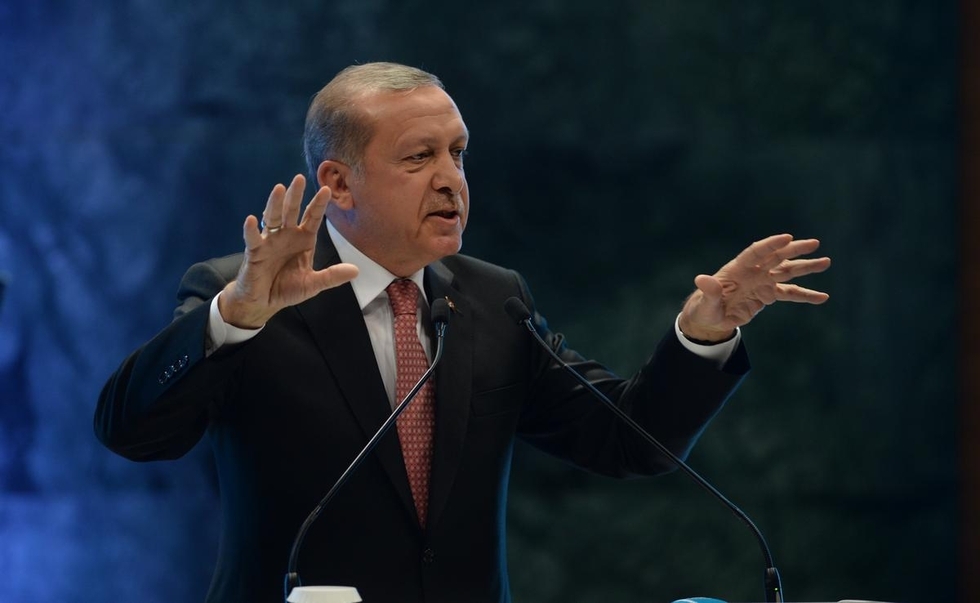

In a speech he delivered upon endorsing the caretaker government, Erdogan called on the Turkish people to opt for security and stability in the forthcoming elections. It is obvious that Erdogan, the founder and former leader of the AKP, meant to say that the Turkish people should once again grant confidence and a parliamentary majority to the AKP and enable it to rule single-handedly. That call may or may not be heeded by the majority of voters.

In one way or another, the AKP has fallen victim to its own success on the Kurdish question. This, in fact, is what permitted the People’s Democratic Party (HDP) to take part in the elections for the first time in Turkish history. If the resumption of the PKK’s armed campaign is to boost Kurdish nationalism, the forthcoming elections are unlikely to change in any significant way the prospects of the four main parties.

There is no doubt that Turkey is divided, like most Islamic countries of the Middle East. The AKP peaked in popularity in the 2011 parliamentary elections, but still fell short of 50 per cent of the votes. The orthodoxy among Turkish political observers, and this seems to be right, is that the core of the AKP's popular support is around 38 per cent of the vote. Increasing its share of the vote means gaining extra support from the conservative Turkish nationalist base, from Islamist Kurds and Kurds who are not radical nationalist and from liberals.

The elephant in the room is the president’s insistence - and he is still highly influential inside the AKP - that the election manifesto should include a pledge to draft a new constitution that would create a presidential system. It was the same pledge in the June elections that drove liberals towards the HDP. The latter also succeeded to attract Kurdish voters of the AKP. Alongside that, the peace process which was led by successive AKP governments cost the party a proportion of the Turkish nationalist votes. In consequence, the share of the Nationalist Movement Party went up to 17 per cent of the votes, that is by about three or four points above its traditional threshold.

The AKP will hold its annual conference in the middle of this September, right before the start of the election campaign. The conference will constitute an opportunity for the party to revisit its discourse, revise its agenda and reflect on the strategic mistakes it made in its last election campaign. It will be the last chance for the AKP to rebuild its relationship with the electorate at large, Turks and Kurds, conservatives, nationalists and liberals, particularly those who decided to desert it during the last elections. Failing that, the next elections will not produce results which will be different from the previous one.

If that were to happen, Turkey faces a return to the era of coalition governments with all the instability that that entails - fudged policies in economics, domestic and foreign policy.

- Basheer Nafi is a senior research fellow at Al Jazeera Centre for Studies.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Image: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan gives a speech during the opening session of the Business 20 (B20) Turkey Summit on 3 September, 2015 in Ankara, Turkey. (AA)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.