When allies fall out: Turkey and the US at loggerheads

The US ambassador in Ankara has been called in by the foreign ministry amid signs of growing differences between Turkey and the US on the role of Kurds in the war against the Islamic State.

American diplomats used to be fond of describing Turkey in private as "an ally they could never do without". The two countries have been allies for over 60 years, though on some issues – notably Cyprus and Israel - they have usually differed.

On Monday this week Turkey’s President Erdogan threw down the gauntlet, suggesting that the USA would have to chose between Turkey and the Kurds. “Are you on our side or on the side of the terrorists?” Mr Erdogan asked stingingly. Inside Turkey his words were regarded as an ultimatum.

More signs of Turkish official displeasure followed within a few hours.

On Tuesday evening, John Bass, the US ambassador in Ankara, was summoned to the Turkish foreign ministry. Just what was discussed is unclear - the US State Department refusing to comment - but plainly the core issue was the continuing refusal of Washington to distance itself from the Democratic Union Party (PYD) Kurds of northern Syria, who up till now have proved the US’s only effective allies on the ground against IS, driving it back at many points in the last eight months, and most recently crossing the Euphrates after taking the Tishrin Dam from it on 26 December.

Though the Tishrin operation was carried out by a mixed Arab and Kurdish coalition, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), it is no secret that the PYD is the active ingredient. It is currently paused, considering whether to press northwards inside Syria and trying to take Manbij, an IS stronghold, on its way to the western Syrian Kurdish enclave of Afrin. If successful, this move would seal off the 98km corridor still open between Turkey and the area north of Aleppo, though the SDF would also have to contend with Russian and pro-Assad forces.

But President Erdogan and the Turkish government have a second and equally strong domestic political motive for opposing the PYD. Historically and ideologically the PYD is an offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), the pro-Kurdish revolutionary movement which has fought a terrorist campaign against Ankara since 1984.

Despite intense pressure from its Western allies to continue with a ceasefire and settlement negotiations begun in 2013, in the first half of last year, the talks collapsed. Since then Turkey has struck at the PKK with a no-holds-barred campaign which has reduced parts of the main cities of the south to rubble and cost over a 1000 lives, and which continues to take an almost daily toll of police and soldiers’ lives, at least 20 so far this month.

The pro-Kurdish Peoples Democracy Party (HDP) accuses the authorities of committing a massacre in the town of Cizre - an allegation which the government firmly rejects, accusing the HDP of involvement in terrorism.

Many of the fighters in the PYD’s armed wing the Peoples Protection Units (YPG) are in fact PKK militants from Turkey who regard the homeland of the Kurds as a unity and ignore existing international frontiers. There has been a series of cases of Turkey delaying or even refusing to admit back the bodies of dead YPG fighters for burial in their towns of origin on the Turkish side of the border.

Given that the USA needs both Turkey’s active support in the fight again IS, in particular the ability to fly from Turkish military airbases and also its PYD Syrian Kurdish allies, it faces a dilemma. It has long placed the PKK on its list of banned terrorist organization and pleased Turkey by doing so.

But the non-Turkish PYD has been consistently treated by Washington as a legitimate body, brushing aside Turkey’s allegations that its members are not only terrorists but are ethnically cleansing non-Kurdish elements in the Syrian population.

Washington did however keep its links with the PYD rather in the background and leant over backwards to stress the importance of Turkey as an ally and frequently repeated its condemnations of PKK terrorism. The last US ambassador in Ankara has said since retiring that there might even be circumstances in which the US would treat the PYD like the PKK. A month ago, General Joseph Dunsford was quoted by the Turkish press during a visit to Ankara as saying that the US shared Turkish concerns over the PYD.

Then this month for the first time Brett McGurk, the US’s cumbersomely entitled “Special Presidential Envoy for the Global Coalition to Counter ISIL” visited the PYD-held parts of northern Syria, including Kobane, and paid his respects to fallen Kurdish fighters there.

It is not clear what caused this shift in policy which the US must have known full well would exasperate the Turkish president and his officials. However, there are other signs of unease between Washington and Ankara. American officials including both Vice-President Joe Biden and John Bass, the US ambassador in Ankara, have signalled strong unease over human rights issues such as freedom of the press and academics. Soon afterwards Turkey’s insistence on excluding the PYD from the Geneva peace talks on Syria contributed to their failing to get off the ground.

Finally, in the wake of the McGurk visit to Kobane, State Department spokesmen were pressed at daily briefings over the PYD and reaffirmed their long-standing position that they do not see it as a terrorist organisation. This is what led to the summoning, and very probably verbal dressing down, of Ambassador Bass.

There have been storms in US-Turkish relations before, sometimes over such seemingly trivial issues as calling the Greek Orthodox Patriarch in Istanbul "Ecumenical" or even fierce press accusations that the US’s embassy’s staff were "lobbying against the government".

In retrospect those episodes seem like storms in a teacup but today with IS, the Russian presence in Syria, and growing concerns about authoritarianism in Turkey, the stakes are high. It is a fair bet that the skilled diplomats of Washington will do all they can to avoid deepening the rift, but with tempers in Ankara very brittle – and Turkey’s cherished policies in Syria seemingly boxed in – relations look precarious, something which will affect the several overlapping crises in the region.

On the other hand, after the shooting down of the Russian jet in November, Turkey has few other friends to turn to outside the Middle East.

- David Barchard has worked in Turkey as a journalist, consultant, and university teacher. He writes regularly on Turkish society, politics, and history, and is currently finishing a book on the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

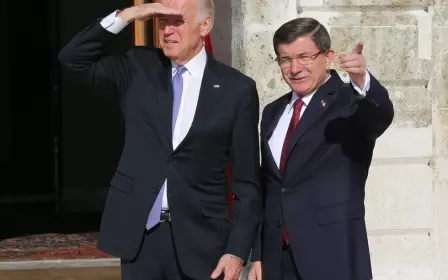

Photo: US President Barack Obama (R) greets Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan prior to a meeting at the US Chief of Mission’s residence in Paris on 1 December, 2015 (AFP).

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.