Violent extremism: How to fight the monster without becoming one

Violent extremism is a global phenomenon and has many causes. It can be motivated by religious, secular or nationalistic ideas. It is also related to the socio-political circumstances in which individuals react to what they consider to be great injustice and oppression. Wars, internecine fighting, civil wars, tribal hostilities, failed states and a host of other factors play a role in the rise and spread of violent extremism. There is more than one reason for the emergence of violent extremism and we need to adopt an integrated approach to understanding its causes and operate at several levels to contain and prevent it.

Such an approach requires work mainly at two levels: the level of ideas and the level of facts. Violent extremism as an idea is a driving force for various terrorist groups from Daesh and PKK to ETA and anti-Muslim Buddhist nationalists in Myanmar. Fighting against them requires a battle of ideas where attempts to justify terrorist methods are rejected based on authentic and authoritative sources.

In the case of Daesh, Muslim scholars and religious leaders have debunked its extremist ideology and shown the fallacy of their logic. A good example of this (effort) is the letter to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of Daesh, by a large number of prominent Muslim scholars and academics in 2014. Numerous other scholars and community leaders have rejected Daesh’s extremist ideology and its futile attempts to justify its barbaric ideology.

Rejecting Daesh’s methodological base, however, is not enough. One needs to show how they distort and hijack the core message of Islam. Indeed, Daesh’s ideology and practice is diametrically opposed to the beliefs and ways of life of more than 1.7 billion Muslims around the world. But a small group of extremists is still able to misuse religion to justify their savagery. Obviously, this is not a particularly Islamic problem. Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism and other religions have been subject to similar (violations and) extremist interpretations. From Baruch Goldstein to Andres Breivik, many have carried out terrorist acts in the name of their religion, country and/or ideology.

How to protect religion from those who attempt to distort it for extremist ends is a critical question for all traditions. Are the principles enshrined in the canonical sources enough to prevent extremist interpretations? What are the methodological principles that maintain the middle path of Islam and address questions of justice, peace and freedom in modern Muslim societies?

The Islamic intellectual and legal tradition has the resources to stem violent extremism. Islamic social and cultural history is filled with examples of how a culture of peace and tolerance can be nourished and sustained from Baghdad, Samarkand and Isfahan to Istanbul, Sarajevo and Cordoba.

Today, Muslim scholars and religious leaders have to find new and creative ways to prevent young people from falling into the hands of violent extremists whether in European capitals or Muslim cities. The trouble is that this message is usually lost in the extremities of the current world order.

This brings me to the battle of facts on the ground. The violent wars and occupations of modern history have caused some of the greatest human tragedies in human memory. The legacy of colonialism, the two world wars, the use of atomic bomb, the spread of weapons of mass destruction, the ethnic cleansing of Bosnian Muslims in the 1990s, genocidal killings in Africa, to name just a few, are among the global calamities that have led to the death of millions of people around the world. Their long-term effects have created extremities and excessiveness that invoke Nietzsche’s "Ubermensch", TS Eliot’s Wasteland and George Orwell's 1984". Their common trait is the sense of being in a state of perpetual war.

This is the same sense that Syrians feel today in the face of the brutal and criminal war of the Assad regime. The Daesh terrorists and others are using the Syrian war to spread their extremist ideology and recruit new members. The war in Syria has become a useful tool now for any group and state that wants to impose its policy on the Levant region. It is a backdrop for a global power play that is not only brutal and irresponsible but also costly and dangerous for everyone’s security from the Middle East to Europe and the US. As long as the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad remains in power and its supporters continue to pulverise Syria to their advantage, Daesh and similar groups will find chaos and destruction as suitable tools to spread their violent extremism.

But Daesh is only the symptom of a larger problem – a problem that goes to the heart of the extremisms of the modern world: the failure of the international system, the sense of despair and nihilism, political and economic injustice, and the uneasy relationship between tradition and modernity.

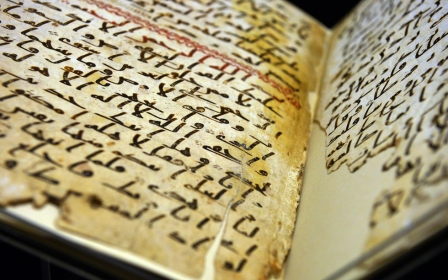

Like all extremist movements, whether religious or secular, Daesh can seek to justify its extremism by referring to other sources – in its case Islamic ones, such as the Quran or the life of the Prophet Muhammad. As numerous Muslim scholars and thinkers point out, a misguided methodology and misplaced ideology can be used to distort any religious text and historical precedent. Al-Qaeda, Boko Haram and Daesh misuse religious sources and references to create an extremist ideology.

Daesh members may quote verses from the Quran or shout Allah akbar (God is great!). But this does not make their acts religious or sacred. The Quran itself warns against those who try to manipulate the commands of God for their own benefits. Daesh is a typical example of a power-seeking violent organisation that uses religious justification but eventually fails at logical consistency and religious authority.

The critical point is that extremism is not necessarily or exclusively a religious phenomenon. It does not need religion to emerge. Like an epidemic, it travels from one place to another and takes on secular, religious, nationalistic and tribal forms. In many instances, it is not the case that some Muslim individuals suddenly become radical and/or extremist. Rather, violent extremism spreads among them and takes on a religious tone.

It would make little sense to reduce extremism to violent killings only. Those killings, as carried out by Daesh recently for instance, must be stopped. But we should not lose sight of the larger picture here: we live in an age of extremism (extremities) whereby doing something in a middle and moderate way is not "cool" and does not register as a norm. In subtle and subconscious ways, the current system of political and economic relations force people to the margins and to the extremes.

In most cases of nascent extremism, there is a fine line between taking a firm and radical position for justice and tripping over to extremism. There are places where one has to be radical and uncompromising: when you have the duty to protect women and children, human rights, the rights of minorities, fight against the occupation of your country and fight against terrorism. But where this morally justified "radicalism"ends and where violent extremism begins is where things get delicate and sensitive.

This is where we need a reassessment of our modern priorities and critically question the overall direction of the present state of humanity. Rejecting extremism in all of its forms, whether Daesh terrorism, sectarian killings, school shootings or Hollywood violence, will be a first step in the right direction.

The trick is to fight the monster without becoming one.

Failed states, weak governments: A global threat

There are multiple reasons for the spread of violent extremism but one key factor is the fact of weak and failed states.

A failed state is usually defined as one that is unable to provide security and basic services to its citizens. The absence of a strong central authority creates acute problems not only for the citizens of that country but also for its neighbours. Afghanistan and Pakistan blame each other for lawlessness and terrorism along their shared borders but the fact is that both states, though at varying degrees, fall short of establishing order and security over all of their territories. Poverty, illiteracy, geographical challenges and tribal/communal loyalties make it difficult for such states to enforce the law.

The danger that the weak and failed states pose to regional and global order becomes multiplied with the globalisation of local problems. The absence of functioning government institutions paves way for disorder, illegality and terrorism. The most devastating consequence is the loss of trust in the state and the rule of law. From Somalia and the Democratic Republic of Congo to Sierra Leone and Haiti, the problems of weak and/or failed state are augmented by the unhelpful policies of regional and global actors.

Since the 1990s, an estimated 10 million people, most of them civilians, have been killed in wars in and among failed states across the globe. Compared to individual terrorist attacks that capture the attention of world media once in a while, the incidents of death and devastation related to weak and failed states is enormous by any measure.

Since the Arab popular revolts began in 2011, a new problem has arisen: governability. About half a dozen states in the Arab world today are either without a strong governing body or run by weak and fragmented governments. In Syria and Libya, state institutions have collapsed, leading to civil war and internecine fighting. In Yemen and Somalia, the central government is extremely weak and unable to assert its authority. Iraq is seeking to recover but about one third of its territories is controlled by Daesh. Lebanon has hardly had any strong governing body since the end of the civil war.

Outside the Arab world, countries such as Haiti, the Central African Republic and Bangladesh, while each having its own unique circumstances, are stuck in the danger zone of failing states.

The citizens of those countries suffer the consequences of insecurity, lawlessness, poverty and internal fighting. But the danger extends to regional and global order. The current global order depends on individual nation-states to establish peace and security in its own territories. Failure to do so cripples both the regional and global order.

The impact of weak and failed states cannot be overstated in the rise, finance and spread of terrorism. Daesh has become a powerful terrorist organisation because of the suicidal policies of the Assad regime that turned ungoverned Syrian territories into a breeding ground for militants. The lack of strong central government in Iraq, coupled with Maliki’s divisive and sectarian policies, has enabled Daesh to control key strategic territories of Iraq.

Terrorists do not necessarily come from failed states only. Homegrown terrorism in wealthy nations is the result of a complex set of social, economic and political factors. But one thing is clear: where state institutions fail, terrorist groups and warlords fill the gap.

In the face of failed states and weak governments, responsible political figures, civic communities and religious leaders cannot change the course of events in their countries. Those in the West who accuse Muslims of not condemning terrorism simply miss out on this fundamental fact. Religious figures and community leaders do condemn violent extremism and terrorism but they suffer from the same consequences of weak and failing states.

The legacies of colonialism, local/national problems and the structural injustices of the current global order have contributed to the rise of failed states in the 21st century. Divisive and self-centric policies of powerful states and non-state actors are exacerbating the problem.

A new strategy is needed against Daesh

The recent terrorist attacks in Ankara, Istanbul, Baghdad, Brussels and Pakistan have once again unveiled the fragile nature of the world in which we live. But they also underline the urgency of developing new policies against violent extremism and terrorism in all of its forms.

Three main lessons can be drawn here. First of all, the anti-Daesh strategy needs to be revised. There is no doubt that this menace must be destroyed. Muslim and Western countries have to work together to eliminate Daesh, al-Qaeda and similar terrorist organisations whether in Syria, Iraq, Somalia, France or Belgium. But the current strategy, which has focused primarily on air-bombing Daesh targets in Syria and Iraq, has failed to stop Daesh from striking in Syria, Turkey, Europe and the US. The war in Syria continues to feed the Daesh monster. The longer we let this war continue, the deadlier Daesh terrorism will become. Daesh has reached its current level of network and impact primarily because of the war in Syria and the deep security and political problems in Iraq.

Daesh terrorism should not make us forget the fact that the Assad regime has killed close to 400,000 people, more than any other terrorist organisation. It has turned millions of Syrians into refugees and internally displaced people. Disregarding this horrible fact in the name of fighting Daesh deepens the sense of alienation and resentment. Paradoxically enough, the Russian backing of the Assad regime is feeding Daesh which sees the American invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the current support for Assad as justification for its existence.

Secondly, there are no good or bad terrorists. Regardless of its ethnic, religious or political motives, terrorism is terrorism everywhere. It is neither logical nor moral to treat Daesh as a terrorist organisation that struck in Paris and Brussels but not the PKK that struck in Ankara twice over the last two months. By allowing the PKK to manipulate the system in Europe, the EU countries fail the test of consistency against terrorism. PKK terrorism cannot be justified in the name of fighting Daesh in Syria. As the recent Ankara and Istanbul attacks show, Daesh and PKK, though coming from opposite ideological-political backgrounds, are united in their terrorism directed at Turkey.

At this point, intelligence sharing and cooperation against terrorism is key to preventing future incidents. As it has become clear after the Brussels attack, the Belgian authorities failed to act on intelligence which Turkey provided with an official note that Ibrahim el-Bakraoui, one of the suicide bombers, was a foreign terrorist fighter. He was first arrested in Gaziantep and then deported in June 2015 to the Netherlands at his request.

Over the last three years, Turkey deported more than three thousand individuals and put another 37,000 on a no-entry list for suspected ties to terrorism. A significant number of these individuals come from European countries.

Thirdly, the anti-Muslim backlash after every terrorist attack plays right into the hands of violent extremists. The European and American Islamophobes wasted no time in using the recent attacks to manipulate the anti-Muslim sentiment for their political goals. Homogenising discourses about Islam and Muslims hurts the fight against radicalisation and violent extremism. It alienates the vast majority of Muslims and helps the extremists. Essentialising Islam does not solve any political problems nor does it increase our security. Furthermore, ISIS does not recruit solely on theology; it manipulates political facts and recruits petty criminals, adventurers and misfits from all walks of life. Violence does not need religion to justify itself.

Research shows that right-wing extremists kill more people than terrorists with a Muslim name. What is worse is the fact that Islamophobia and anti-Muslim racism has become a rallying ground for both the far right and the leftist circles in the West. The far-right conservative groups invoke ethnic and religious purity against minority Muslim communities and the left-liberal pundits resort to feminism and secularism, among other ideas, to demonise Muslims. What unites these unlikely allies is their collective stereotyping of Islam and Muslims.

Caught in between violent extremism and anti-Muslim racism, ordinary Muslims are victimised twice. On the one hand, they suffer from the brutal attacks of Daesh in places like Syria and Iraq as Daesh has killed far more Muslims than non-Muslims. On the other hand, the Islamophobes, who use Daesh terrorism to make cheap political points on the anti-Muslim wave, subject ordinary Muslims to discrimination, guilt by association and racism – offences that they would not dare inflict on other groups.

Muslims are asked to denounce Daesh and its likes. They do. But it does not register as a fact and does not make into daily political commentary as a given. Every time a terrorist event happens, Muslims are turned into potential suspects. But the same questioning is never applied to ordinary Germans in regards to the neo-Nazis, Norwegians in regards to Andres Breivik or Americans in regards to the KKK and Timothy McVeigh. European and American terrorists are treated as terrorists with very little or no commentary on their religion and cultural identity.

Pluralism and the 'Muslim question' in Europe

At this point, let me turn briefly to an issue that feeds the violent extremists in the Muslim world, and that’s the anti-Muslim racist and Islamophobic waves that play right into the hands of Daesh, al-Qaeda and the like.

In an all-too familiar scenario, after every terrorist attack in the West, the debate turns into one about pluralism and what to do about the “Muslim Question”.

In her insightful book entitled On the Muslim Question, the political scientist Anne Norton applies Karl Marx’s concept of the “Jewish Question” to the current debates about Islam and Muslims in Europe and the US. For Marx, the "Jewish Question" was a test case for the Enlightenment. The success or failure of the Enlightenment project was dependent on the acceptance or rejection of Jews into the new Europe as free and equal human beings and citizens. Free from the fear of subordination, oppression and assimilation, the Jews, who, as a suspect minority, had been vilified and persecuted for centuries, were supposed to be part of the new European community. The Jewish Question could have opened new spaces of opportunity for multiculturalism and coexistence in the West. Instead, it ended up in one of the most horrible episodes of modern European history: the Holocaust.

Today, the Jewish question seems to be replaced by the “Muslim Question”. Professor Norton argues that what is at stake in regards to the "Muslim question" is not Islam and Muslims per se but the West itself, and its thinking about reason, freedom, equality, justice and pluralism. From conservative right to liberal left, the debate about Islam is shaped by domestic anxieties about urban life, migration, capitalism, unemployment, party politics, sex, race, consumerism, religion, morality and a host of other issues that can easily be discussed without any reference to Islam, Muslims, or the Middle East. The social and political anxieties of Western societies thus present a distorted picture of both Islam and the West and poison the precarious Islam-West relations.

Referencing Islam in such debates, however, brings a degree of comfort and convenience because it projects the problem to some "other" in a distant world. The Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor is thus right when he says that the current debate about multiculturalism in Western countries has become a debate about Islam and Muslims. According to Taylor, multiculturalism has become suspect and linked up with Islam because “almost every reason for toleration’s apparent fall into disrepute concerns Islam.”

After every crisis moment, “Islam” becomes part of a confused debate about how far multiculturalism will go. Block thinking and stereotyping dominates political and media discourses about the supposed true identity and soul of Europe versus Muslim societies.

Muslim communities respond with an equally distorted and confused mindset. They apply the same block thinking and stereotyping to the very Western societies they complain about. The breakdown of rational communication between Muslim and Western societies reaches disturbing levels of confusion, prejudice and mistrust. According to the 2007 Gallup World Poll, “Muslims around the world say that the one thing the West can do to improve relations with their societies is to moderate their views towards Muslims and respect Islam”.

Another study conducted in 2008 by the World Economic Forum and published as Islam and the West: Annual Report on the State of Dialogue notes that the vast majority of Muslims believe that the West does not respect Islam, whereas many Westerners hold just the opposite view and believe that the Westerners do respect Muslims. This is more than a communication breakdown. Much work is needed here to overcome this mental abyss.

In a similar way, Europeans’ confidence in their liberal, pluralistic model of socio-political life betrays a sense of disconnect if not outright hubris. In 2007, Louise Arbour, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights at the time, said that “bigotry and prejudice, especially in regard to Muslims, were common in Europe”. Seeing the larger danger, she “called on governments to tackle the issue.” But in a telling note, she added that Europeans “are shocked at times when it is pointed out that bigotry, prejudice and stereotyping is still sometimes very present in their attitude toward others.”

Crisis in the Muslim world

In my concluding remarks, let me to turn to the Muslim world, which needs to have a reckoning of its own and re-asses its priorities.

Neither sure of itself nor engaging the globe constructively, the Muslim world vacillates between the glory of a brilliant past and the apathy and misery of the present. Many Muslim countries suffer from political crises, economic backwardness, weak infrastructure, bad education, lack of competitiveness in science and technology, polluted and badly managed cities and environmental hazards. They are paralysed by social inequality, injustice towards women, sectarian conflict, extremism, violence and terrorism. Islam’s core teachings of peace, justice and compassion are lost in the brutal race for worldly power.

The legacy of imperialist interventions, failed states, poverty, illiteracy and the sense of dispossession and alienation has created deep wounds in the social and political landscape of the Middle East. A divisive identity politics has become a powerful ideological tool. In the name of religion, nationalism or anti-imperialism, political opportunists and extremists have used the longstanding grievances of ordinary people to advance their political goals.

This is all true, and more: Western democracies have betrayed their own values and principles. They have watched the occupation of Palestine and its expansion for almost 50 years, supported the coup in Egypt, created disastrous conditions in Iraq, failed to support the Syrian people, turned a blind eye to the suffering of millions of people in Myanmar, Somalia and other places. They are the biggest producers of deadliest weapons in human history and sell them to poor countries. They run an economic system that favours the rich and keeps the poor at the bottom. Some justify discrimination and racism against Muslims in the name of fighting religious extremism. These are all true, and the list goes on.

But blaming others only does not solve our problems; rather, it leads to intellectual laziness and moral conformism. It is one thing to take pride in the great achievements of the classical Islamic civilisation; we should all do and learn from it. But it is more crucial and meaningful to reproduce them today, which should be the task of an effective educational system. It is meaningless to only blame the West or the international system for the ill fortunes of the Muslim world without first stopping the internal bleeding in Muslim societies.

A moment of reflection reveals the bitter truth: just like the powerful countries of the world, Muslims have betrayed their own tradition. They have allowed injustice, inequality, poverty, extremism and terrorism to fester in their midst. They have failed to address legitimate grievances in morally sensible and rationally effective ways. Instead of working to resolve their problems with wisdom and patience, they have resorted to intolerance, fanaticism and violence. The result is the spread of violent extremist groups that undermine the fundamental principles and core teachings of Islam.

The Muslim world needs to have a moment of reflection and reckoning. This needs to start from within. The Islamic intellectual tradition insists on the complementarity of the "inner" (al-batin) and the "outer" (al-zahir): what is out there is a reflection of what is within you, and the good within you needs to come out and establish peace, justice and mercy in the outside world. As the Quran says, “God will not change the condition of a people until they change what is in themselves.”

Muslim leaders, scholars, and men and women of letters, business and community work need to step forward and build a culture based on faith, reason and virtue. They can and should reestablish the self-esteem of the Muslim faith without arrogance and without discrimination against those of other faiths. They can show the way to engage the world in a creative and constructive manner just as al-Farabi and Ibn Sina did in philosophy, Biruni and Ibn al-Haytham did in science, Ibn al-Arabi and Mawlana Jalal al-Din Rumi did in spirituality, the Andalusian rulers did in southern Europe, and numerous Muslim rulers, scientists and artists did in their respective fields.

Blessed with rich natural resources, Muslim countries need to invest in education, good governance, urban development, poverty eradication and youth and women's empowerment. There are only a handful of Muslim countries that seriously invest in these fields. More countries need to make better use of their resources so that Muslim lands once again become regions of peace, justice, faith, reason and virtue.

This requires better governance, better politics and better planning. But above all, it requires a revolution of the mind whereby we redefine our relationship with the world and treat it as a "trust" (amanah) given to us. And all this starts with purifying our inner state and taking care of God’s creation with intelligence and compassion.

- Ibrahim Kalin is the spokesperson for the Turkish presidency. You can follow him on Twitter @ikalin1. This essay is based on a talk given at Al Sharq Forum in Istanbul in early April.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: An Iraqi pro-government forces member mans a tank on 30 April, 2016 during an operation to retake the town of al-Bashir, south of the city of Kirkuk, from the Islamic State group (IS).

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.