All strangers are kin: How classical Arabic language connects people

Zora O’ Neill’s book, All Strangers Are Kin: Adventures in Arabic and the Arab World, derives its title from a verse in a pre-Islamic era poem by the renowned poet Imru al-Qays. In the prologue the author explains how she came about writing the book. She had studied Arabic during a summer in Egypt when she was in her twenties, fell in love with the language and took it up after her return home to America. However, after years of studying it, she let it go as she built a life and settled down. Only, the language did not let go of her, making her see a connection to it in places and circumstances around her.

When she visited Egypt again after almost a decade, she found that she still could converse in Arabic not too badly and this rekindled the desire to learn the language again. This time she resolved to focus on the spoken language and not the classical, written one she had studied. In this quest to learn Arabic as is it is spoken in the Arab world, she decided to visit various countries in the region known for their unique dialects - Egypt, UAE, Lebanon and Morocco.

As she travelled through these countries she found even the meaning of words differed from region to region: what she had known to be the word for lemon in Egypt was orange in Lebanon; mashi which she used in Egypt for OK meant "nothing" in Morocco; the word for wardrobe in Egypt meant tyres in Lebanon. These differences put her in perplexing situations, like the time in class in Lebanon when everyone was talking about, "burning wardrobes on the highway last night" which did not make sense at all till someone explained that they were talking about the tyre-burning incidents of the previous night.

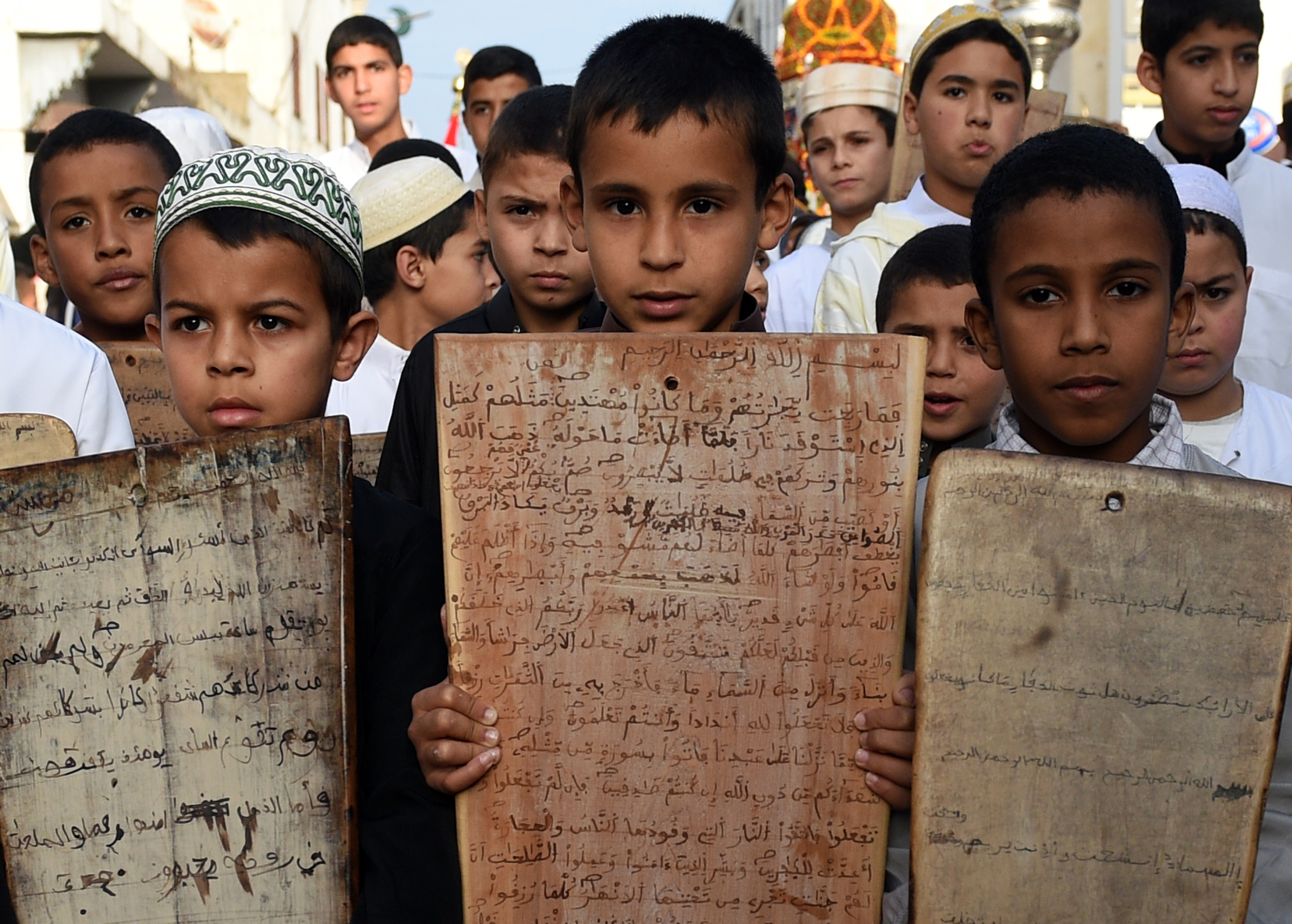

One of the reasons she cites for wanting to learn spoken Arabic was because the formal written language, or Fusha as the classical version is called, was rich and heavy, with myriad rules defining its structure. She discovers that Arabs do not learn Fusha as a mother tongue, rather most students in the Arab world learn three forms of Arabic: the language of the Quran, the modern form of Fusha used in newspapers and literature, and their own spoken dialect. In Lebanon, she finds dialects within dialects and realises how the spoken language can give away political and regional affiliations. Fusha in this context is the neutral language that does not give away what the vernacular could regarding the nativity of the speaker.

"I had considered Fusha an anchor tied to my ankle, dragging me to the bottom of the sea. Now in its regimented order, logical spelling and vocabulary that predated Lebanese identity politics, it looked like a life preserver."

Later on during her travels she confesses that her grounding in this very same, highly structured version helped in getting across what she wanted to say, making her realise that it was the foundation and there were no short cuts to learning it.

O’ Neill returned to Egypt to learn the Ammiya – spoken dialect - in the country. After enrolling for classes, she used every opportunity to walk around, getting herself in situations where she would have to talk to the people, testing her knowledge and to her delight finding the people responding to her in their own language. It also puts her in unusual situations, taking a train to a camel market, sharing food with a family picnicking at the grounds of a museum. Peppered with minute descriptions, the reader gets to see glimpses of Egypt, the people on the street, farmers tilling the soil, men and women dreaming of political changes in their country, sudden violence that erupts on the streets and the flagging enthusiasm of the people as they battled political situations.

In the Persian Gulf she arrives in the UAE and later visits Qatar and Oman. In the UAE she runs into the peculiar problem of not finding anyone willing to talk to her in Arabic. One day she gets into an accident and far from being perturbed about it she is thrilled that the five men in the other car were yelling at her in Arabic. Next day at the police station she gets to practise the language again, making her an instant celebrity inside, with her papers cleared efficiently and cheerfully.

Another time, while driving towards the sand dunes of Abu Dhabi she decides to stop for hitchhikers so that it will give her a chance to practise the language. The first man just looks at her curiously and sits primly in the seat without uttering a word, while the second one says one line and shuts up thereafter. It is only the third person she picks who actually starts talking to her and he, much to her delight, is an Egyptian with whom she can practice her Ammiya. Describing her jubilation she says, "It is as if I had finally tuned in to the right radio station after cranking the dial through patches of static."

As the author travels through the various emirates of UAE, Qatar and Oman, she brings attention to the changing landscape and culture of the region. Whether travelling on a dhow in the Persian Gulf, walking to the centre of the city of Tripoli, or visiting tradesmen in a medina in Tangier, the reader is shown glimpses of the life of the people living in the region.

O’Neill takes great effort to talk in detail about the language, the complex root system, the vowels and consonants, how a seemingly small variation can mean diametrically different things. A student of Arabic or those familiar with the language will find the minute explanations delving into the semantics of the language very interesting, lifting their experience of reading the book.

The beginning, especially is devoted to explanations of the language which could make heavy reading for those unfamiliar with the language. But the pace picks up soon enough with the reader getting to see the cadence of life in different societies in the Arab world. The narrative is crisp and unemotional and the beauty of the prose is that no judgement is passed nor comment given, leaving the reader to form their opinions, the author’s job restricted to describing events as they happened.

For me, my knowledge of Arabic being restricted to the verses in the Quran, the author’s explanations helped me discern why we are told time and again while reading the Holy Book about the importance of making sure of our pronunciation, to be sure of our "sha" and "sa" and other inflections, because a slight difference could result in totally different meanings. For example, the difference in saying Shi’r and Si’r could change the meaning of the verse that says, "We have not taught the Prophet the price," when it actually meant, "We have not taught the Prophet poetry."

"All Strangers Are Kin: Adventures in Arabic and the Arab World", written by Zora O’Neill, and published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (June 14, 2016), is available on Amazon.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.