What are the odds of putting Blair in the Hague for what he did to Iraq?

With the Iraq Inquiry headed by Sir John Chilcot set to finally report on Wednesday, it is important to remember the legal questions being considered by the Blair government as they geared up for the invasion of Iraq in March 2003.

With the prime minister under intense pressure from a growing anti-war movement and rebellious Labour Party MPs, in July 2002 the Attorney General Lord Goldsmith told Tony Blair there were only “three possible legal bases” for attacking Iraq. These were “self-defence, humanitarian intervention, or UNSC [security council] authorisation”. The first and second justifications were out of the question, Goldsmith noted.

Things were equally fraught at the Foreign Office, with Sir Michael Wood, the department’s chief legal adviser, warning Foreign Secretary Jack Straw that invading without a second resolution would "amount to the crime of aggression".

Despite applying huge amounts of pressure on members of the security council, the UK and US failed to obtain a security council resolution. The UN Secretary General Kofi Annan declared the war to be in contravention of the UN charter, as did figures ranging from senior judge Lord Bingham to Nobel Peace Prize winner Desmond Tutu and prominent American neoconservative Richard Perle.

“It is generally agreed, by… most international lawyers that the invasion and occupation of Iraq in 2003 was illegal, contravening the prohibition on the use of force in the UN Charter,” notes Bill Bowring, Professor of Law at Birkbeck, University of London.

“The war is responsible for millions dead and displaced, the country is still in flames and there have been no sanctions whatever against those who prosecuted it,” Lindsey German, the convenor of Stop the War Coalition, tells me. “We are not lawyers but many would like to see Blair in The Hague, and this is an extremely popular demand within the anti-war movement.”

It’s a popular demand among the wider public too – a ComRes/Independent poll in 2010 found “37 per cent of people believe that Mr Blair should be put on trial for going to war with Iraq”. However, while the expert consensus and public’s anger are well known, the legal technicalities surrounding if, and how, Blair and his colleagues could be brought to trial are rarely explored.

For example, the International Criminal Court [ICC] at The Hague is the only body that has jurisdiction to prosecute the “crime of aggression”. However, it turns out the ICC only agreed on an official working definition of the term in 2010. And, more importantly, they also agreed that the validity of a case would be determined by the UN Security Council and that it would not consider cases retrospectively.

Professor Bowring and Professor Gerry Simpson, chair in public international law at the London School of Economics agree, with the latter noting: “It is virtually impossible for this ‘crime’ [the crime of aggression] to be prosecuted by an international court.” Therefore, the chances of Blair standing trial are “extremely slim”, Professor Simpson explains.

Similarly, in 2006 the House of Lords held that the crime of aggression was not part of domestic law and would need an Act of Parliament to be incorporated. Therefore, Blair “cannot be prosecuted in the UK’s domestic courts for aggression,” noted Dapo Akande, professor of public international law at the University of Oxford, on the European Journal of International Law’s blog in 2009.

What all this means, as journalist Richard Hall explained in 2010, though, is, “There was no legal case for launching the war” but there is also “no legal basis to prosecute for it”.

Possible routes to prosecution

All this will be deeply frustrating and disappointing for the millions of people who marched against the war and want the Blair government held to account. But all is not lost for them. There are, it seems, a few other viable options.

So, while the chances of prosecuting the Blair government for its illegal and aggressive invasion are currently close to zero, attempts are in progress to bring the UK government to account for war crimes committed by British forces during the occupation itself. Based on a dossier compiled by Public Interest Lawyers and the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights, “two years ago, the new [ICC] prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, commenced a preliminary investigation into possible war crimes committed by members of the government in the following period of occupation,” Professor Bowring explains.

The BBC reported the dossier contained evidence of what they said was more than 400 cases of mistreatment or unlawful killings carried out by UK forces. “Blair could have been, and perhaps may be, prosecuted for war crimes at the ICC in The Hague,” Professor Bowring believes.

Furthermore, though it is still unlikely, Professor Simpson notes “a foreign court is a little more likely” to prosecute the crime of aggression, though Blair “would have to travel to somewhere with a crime of aggression on the statute books”. Philippe Sands QC, professor of law at University College London, concurs, telling the Daily Mirror in 2010 “When Tony Blair travels he now gets legal advice on where he can go and the pattern of extradition agreements.”

There are, according to Sands, approximately 50 countries which have enshrined the crime of aggression into their law and would therefore be unsafe for Blair to visit. “The possibility of a national prosecutor going after Blair in some foreign jurisdiction is reasonably high”, he added.

With legal prosecution and sanction very unlikely in the UK itself, it looks like it will continue to fall to the court of public opinion to pass judgement and punishment on Blair and his close conspirators.

One thing is certain – Blair’s reputation is shot to pieces, with the former prime minister unable to do book signings without protests, or appear in public without people trying to carry out a citizen’s arrest. The Iraq war’s toxicity continues to inform British politics, with potential challengers to Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn hindered by their support for the war.

“The publication of the Chilcot Report will be very important,” notes Professor Bowring about the legal questions surrounding the Iraq war. The content of the report will, of course, be central to the debate, but arguably the deciding factor on how this plays out will be the response from Corbyn’s Labour Party, the media and the public.

Stop the War Coalition are holding a protest at the report’s launch in London on 6 July and then a rally on 7 July. “We will do everything we can to make clear what the issues of legality, lying and the creation of future chaos really mean,” German says. “We don't know whether Chilcot will help pin the blame on the guilty, but we do know this remains an issue of immense importance to millions of people in Britain.”

- Ian Sinclair is a freelance writer based in London and the author of The March that Shook Blair: An Oral History of 15 February 2003. He tweets @IanJSinclair

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

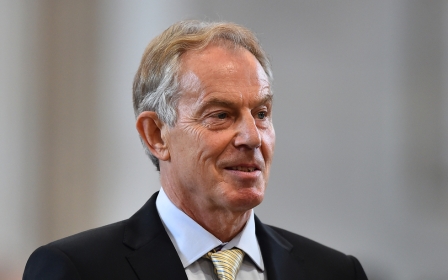

Photo: An anti-war protestor wears a mask of former British Prime Minister Tony Blair as he stands in a mock prison cell outside the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre in central London, on 21 January, 2011 (AFP).

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.