From windowless room to the global stage: The rise of Mashrou' Leila

NEW YORK, United States - She could not understand the words they sang, but Tara Messenger fell in love with Mashrou’ Leila anyway. In 2009 or 2010, she said she stumbled across one of the indie Lebanese band’s music videos on YouTube - the one with the eggplant she recalled - while scouring the internet for music.

For her, the Arabic lyrics gave their music a poetic bent, and she relished the stylistic melding of rock and traditional-sounding chords. One day, she imagined, Mashrou’ Leila would go global.

“I’ve been waiting to see them for a long time,” Messenger, 41, from Staten Island, said as she stood in the dim, thrumming basement of the hip New York City venue Le Poisson Rouge late in June, waiting with a friend for Mashrou’ Leila to take to the stage.

The climb from playing in small Beirut bars to the international stage has not been quick or easy.

Eight years ago, the band started out with about 13 university students experimenting during late-night sessions at the American University in Beirut (AUB).

By the time they made their debut in New York, the band had slimmed down to seven seasoned performers. Firas Abou Fakher, Mashrou’ Leila’s guitarist, keyboardist and composer told Middle East Eye: “None of us really had any musical training...We relied a lot on what we thought was good music across the ages."

The group did not initially plan to make it this far, but their fan base kept growing. They played major concerts in Lebanon and soon were being asked to play in other parts of the region.

Little by little, the band gathered more attention internationally, gaining fans across Europe and then America. As the five remaining members hit the stage in New York, they were clearly in their element playing before a packed, adoring, pulsating crowd.

Yet in recent months the band has not just been making headlines for its music. In April, Jordan banned the group from performing despite the fact they had played to packed out crowds at the Ampethetre three times before.

The governor of Amman, Khalid Abu Zeid, said at the time he had decided to cancel the gig because some of the band’s songs “contain lyrics that are not appropriate in Jordanian society,” an apparent reference to Mashrou’ Leila’s pro-LGBT stance.

The move made international headlines as many took to social media to criticise the government. Within days, authorities backed down amid growing pressure, but the incident only helped raise Mashrou’ Leila’s profile further, recruit a new wave of international fans and galvanise the band to keep playing and breaking boundaries.

“I’d like to believe that even though that may be an entry point for a lot of potential listeners, it’s the quality of the music that keeps them there,” Abou Fakher said.

Humble beginnings

The global attention is a world away from the band's humble origins.

In early 2008, architecture students Omaya Malaeb, Andre Chedid and Haig Papazian put out a call to classmates interested in gathering and playing some music, just for fun. About 13 or 14 people - mainly friends and acquaintances - showed up for those nighttime jam sessions.

In that first month - it was perhaps February or March, Abou Fakher said - the group gathered once or twice a week, in a tiny windowless room designated for the school music club. It had blue soundproof panelling and a “s****y drum set,” he recalled.

Even in the early days, they began sketching the outlines of a few songs. Soon it became apparent that the musical instincts and tastes of seven members of the group - keyboardist Malaeb, guitarist Chedid, violinist Papazian, along with drummer Carl Gerges, singer Hamed Sinno, guitarist Abou Fakher, and bass guitarist Ibrahim Badr - clicked particularly well. From this, Mashrou’ Leila, which translates loosely as “project of the night,” was born.

Bye bye Beirut

Their first performance was hyper-local, at an exhibition of student work at the architecture school at AUB. By June, they had begun performing at local festivals and while the group went their separate ways for the summer, they returned and started recording their first track, "Raksit Leila".

They entered it into the Lebanese Modern Music Contest in March 2009 and won, paving the way for them to release their first album later that year.

As their local following blossomed, so did their musical clout. In July 2010, they played at the Byblos Festival in Lebanon, alongside acts like the Gorillaz and Riverdance.

Still, it was not until requests started coming in for Mashrou’ Leila to perform outside of Lebanon - at the Doha Tribeca Film Festival in October 2010, then in Dubai the following spring, then Cairo that summer - that the band recognised their music might follow a more serious trajectory.

“It was the moment where we crossed over from just a little Beirut act among our friends to something people were watching so far away,” Abou Fakher said. “We started to say, ‘Wow, people are starting to pay attention'.”

By the time Abou Fakher, Sinno, Badr and Gerges were graduating in 2011, Mashrou’ Leila's fame had spread to Europe. They played their first concert on the continent at Serbia’s Exit Festival in Novi Sad in September, and then released their second album, El Hal Romancy, a few months later. That October, they were on stage in Amsterdam and Paris.

By August 2012, the band - slightly diminished after Chedid's departure - come to a decision: It was time to go for it. They quit their jobs and moved to Canada to record their third album, Raasuk.

“We thought, ‘If we’re not going to do it now, it’s never going to happen,’” Abou Fakher said.

Malaeb's departure followed, but so too did Mashrou’ Leila's fourth album, Ibn El Leil, which was released last November.

A New Sound

These days, the streamlined five-member lineup, says it is stronger than ever and determined to make a serious impact in the key US market.

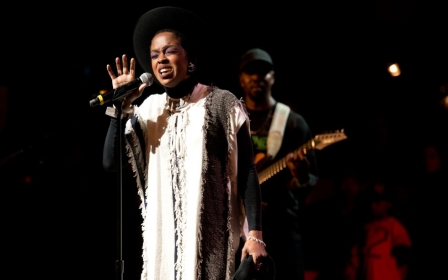

As the band appeared in New York recently, Sinno - who has come out as openly gay - cupped his hands around the microphone as the sequins draped over his black sleeveless shirt shimmered.

“Upon my body, upon your body,” the audience at Le Poisson Rouge chanted softly, as Sinno rose to his toes and crooned one of the band's newer hits, "Kalaam". Beneath the blend of voices throbbed a drumbeat, unhurried yet inexorable, while spaces lingered between patient piano chords.

Since the irreverent-sounding, often bouncy and more focused tunes of its first album, Mashrou’ Leila has shifted into layered, lush soundscapes that frequently take on darker moods. Yet the same conviction stokes their sounds. They still contain sex and politics - the stuff of rock’n’roll - and the same musical seeds that first enchanted their Beirut fans, an incisive glimmer or a soaring line from Papazian’s violin, or Sinno’s sometimes distressed, sometimes throaty vocals. The band's determination to rip up the Arab pop music playbook is ever-present.

“From the beginning, we wanted to make sure that we’re making music in Arabic that doesn’t play by the rules that are set by the pop industry,” Abou Fakher said.

This independent spirit has also dominated the band's approach. They have turned down offers from record labels, using instead the internet to build their fan base in order to ensure they continue to retain control over their sound.

“The history of rock'n'roll is much closer to our history, which is, the history of rock'n'roll is basically saying, 'F*** you' to everybody,” Abou Fakher said. “In a sense, that’s how we operate.”

The band that won’t obey

Despite the band's determination to break out and do something unique, its admirers, critics and reviewers alike often seize on a shortlist of facts to define them. Much is made about Sinno being openly gay and also the group's "authority-baiting lyrics,” as the Guardian put it. The brief Jordanian ban earlier this year only helped to bolster that image further.

But the band continues to insist that musical development matters more than headlines. Abou Fakher says he listens to everything from Beethoven, to Radiohead’s Johnny Greenwood, and the Talking Heads’ David Byrne for inspiration, and fiercely admires Paul McCartney for still writing music and experimenting at the age of 74.

“You cannot find anything like it in the Arab world,” Yossi Monsi, an Israeli from Tel Aviv, who recently saw the band for the third time, told MEE. He said he fell in love with their “new” and “indie” sound after a Palestinian friend introduced him to the group.

“One day,” Monsi said, “they will play in Israel.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.