Facing disaster: The Muslim Rohingya of Myanmar

Farouk’s restrained manner contrasted unsettlingly with the slow creep of tears along the fringes of his cheeks.

'They took my child and threw him into the fire by his neck'

- Farouk, Rohingya Muslim

A fine-featured, skeletal middle-aged man, (his name has been withheld at his request), he spoke haltingly as he describes how and why he fled his native Myanmar.

“The fires started at my house at 8.30am on the first day,” said Farouk, adding that they were started by a local Buddhist mob accompanied by the Myanmar army.

“They fired weapons at the children and the elder people who were hiding in the paddy fields. They took my child and threw him into the fire by his neck. He was four years old.”

A history of violence

Farouk’s account was one of several wrenching testimonies given to Middle East Eye by members of the Rohingya Muslim community in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh.

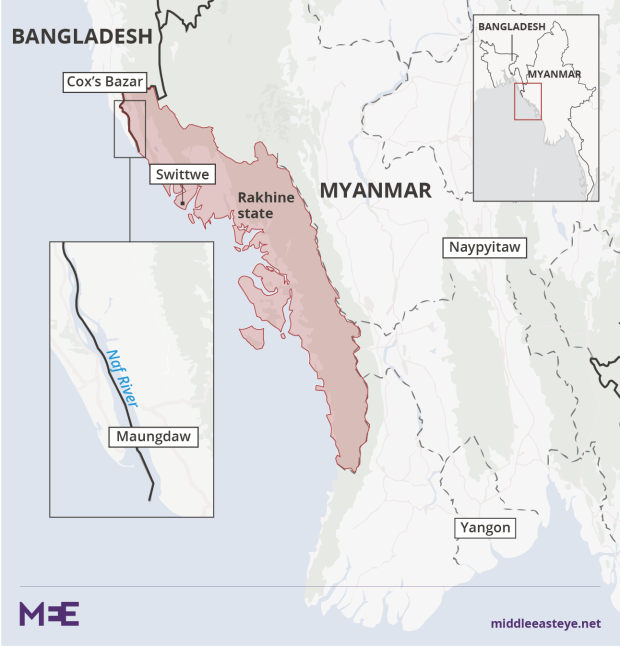

This mostly stateless minority have endured decades of persecution in Rakhine, punctuated by occasional pogroms, the latest of of which may be occurring now.

In 2012, tens of thousands of Rohingya Muslims were burnt out of their homes across Rakhine and forced to live in squalid camps for the displaced. According to Human Rights Watch, it was part of an ethnic cleansing campaign involving state security forces and Buddhist mobs.

Since then, the Rohingya Muslims have seen their few remaining rights eroded further, a process culminating in outright disenfranchisement prior to an historic poll in 2015, the first openly-contested general election in 25 years.

The total death toll since 2012 is unknown: successive governments have sealed off areas hit by violence, and official estimates have been impossibly low. However, agencies of the United Nations believe the number is at least 1,000 dead in recent months.

"The talk until now has been of hundreds of deaths. This is probably an underestimation - we could be looking at thousands," said one of the officials, speaking on condition of anonymity, Reuters reported.

Myanmar government in denial

The latest round of violence began in October 2016, when a group of Rohingya militants conducted a surprise attack against three border guard police posts near Maungdaw, leaving nine dead.

Although the assaults, by a limited group of insurgents, were the the first attack of this kind for decades, rights groups have said that the Myanmar security forces targeted whole communities retributively.

Until recently, the Myanmar government in Naypyidaw simply responded to such charges with blanket or pat denials. A foreign ministry spokeswoman summarised the official stance by stating that, when it comes to allegations of abuse levelled by the Rohingya Muslims, “the things they are accusing us of didn’t happen at all.”

Aung San Suu Kyi, recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize and once an embattled democracy campaigner, is now de facto head of Myanmar’s government. She has presided over this cruel farce, going so far as to allow a social media page run by her office to publicly shame a woman who alleged that she had been raped by security forces

Elsewhere, her office attempted to debunk other allegations of rape, including those contained in a report by The Guardian.And lawmaker Aung Win, who led an earlier inquiry into the allegations against the army, told Middle East Eye that “the [non-Rohingya people] from the military and the police are not interested in ‘Bengali’ [the term used for Muslim Rohingya] women because they are very dirty.” The line, which he also used during a notorious interview with the BBC, was followed by a short laugh.

In the aftermath of the UN report, the government relented on its months-long campaign of refutation. Instead, in February 2017, it issued a bizarre, self-refuting statement to a BBC journalist, claiming that “our position is not a blanket denial... we will cooperate with [the] international community.”

'The things they are accusing us of didn’t happen at all'

- Myanmar foreign ministry spokeswoman

In a recent development, the army announced that it would investigate itself over allegations of abuses against the Muslim Rohingya.

U Pe Than, a parliamentary lawmaker, told The Irrawaddy that the investigation committee members – all members of the military - were “under the control of the Tatmadaw or the government,” but he believed that their enquiries would be “independent and truthful”.

But media access to the conflict zone remains restricted, many government officials reject the OHCHR report and military operations continue.

The only way to access affected Rohingya Muslims and gain a counterview, as a foreign journalist barred from the area, was to interview some of the refugees who crossed the border into Bangladesh.

Tales of horror

If the government are right about Rohingya Muslim “lies,” then the people I met in Cox's Bazar are incredible actors.

Besides Farouk, I talked to a young woman who told me that her husband had been brutally hacked to death in front of her as they fled their house.

“When we went out, my husband encountered the soldiers. We saw that he had been hacked at the neck,” she said. “Our house was burnt down as soon as we left it.”

And another witness, a man in his early thirties, presented what appeared to be a bullet wound in his leg, which he said he sustained during an early morning assault. Eventually he found his way across the Naf river, in a fisherman’s boat, which marks the border between Myanmar and Bangladesh.

“The military came at night,” he said. “They stayed in the military camp. They started shooting at the crowd early in the morning. Some people could escape and some could not escape. [Up to] 50 people died.”

Matthew Smith is chief executive of the monitoring group Fortify Rights, which recently visited refugee camps in Cox's Bazar such as Kutupalong, where the Rohingya make up the biggest group. He said that he and a team of investigators had witnessed multiple cases of new arrivals from Myanmar bearing gunshot wounds, and that they had referred several women who showed signs of rape to medical doctors in the area.

'Soldiers slit throats and burned bodies with impunity. It's horrific. Entire villages were burned to the ground'

- Matthew Smith, Fortify Rights

"We documented how army soldiers raped Rohingya women and girls, and killed untold numbers, including children," Smith said. "Soldiers slit throats and burned bodies with impunity. It's horrific. We documented mass arbitrary arrest and forced displacement. Entire villages were burned to the ground."

Smith added that the government in Naypyidaw had failed to adequately investigate the abuses, while efforts had been made within the administration to cover up or obscure the truth.

"The Human Rights Council should mandate a commission of inquiry into international crimes without delay," he said

Calls for international action

It would appear then that fresh atrocities have occurred against the Rohingya Muslims; at the very least, evidence for lesser types of crime is overwhelming. The International Commission of Jurists notes that hundreds of Rohingya Muslims have been detained without access to lawyers or a fair trial, in contravention of Myanmar and international law. Six of them have died in custody.

Daniel Aguirre, international legal Advisor for the ICJ, told MEE that "unless the judiciary can adequately oversee 'clearance operations,' an international inquiry is the only means to achieve accountability."

Predictably, the findings of both investigations so far (one is completed, the other has produced an interim report) have backed up the government line. The second investigation in particular asserted demonstrable falsehoods as fact and made sweeping, methodologically unsound conclusions based on limited or even irrelevant information.

Yet the probe was described as “independent” by Alok Sharma MP, speaking for the British government in the House of Commons in December. (One wonders at the source of his briefing, given that reliable analysts took precisely the opposite view.) Sharma has, however, consistently expressed concerns in parliament about the situation in Rakhine and other parts of Myanmar, most recently last month.

The government of Myanmar’s response to the OHCHR report was simply to pledge more domestic investigations.

When will the UK make a stand?

Britain’s Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson visited Myanmar in January, where he met Aung San Suu Kyi. According to his own account, one of the topics under discussion was “human rights,” particularly in Rakhine state.

But Johnson did not issue a public call for accountability regarding abuses in the region; there were no press conferences. He did, however, seem to find time to send a video message to a Yangon rugby club.

The UK has form in acting spinelessly on behalf of the Rohingya Muslims. Around the same time that Sharma’s evasive response was issued in parliament, the UK decided to opt-out of a diplomatic call to reopen parts of Rakhine state to humanitarian deliveries, despite the move being led by no less an ally than the United States, along with 13 other embassies.

In many respects, this approach is valid. As others have argued cogently, Suu Kyi’s government are not directly responsible for the violence, perpetrated by the autonomous armed forces. Ultimately, she needs international support to do the right thing. The Tatmadaw (as the military are known in Burmese) still retain ultimate power in Myanmar and, thanks to a constitution they drafted, hold multiple levers over the elected government.

Assassination 'a warning'

Furthermore, a recent disturbing incident confirms the combustibility of Myanmar’s political and religious fissures. On 29 January, Ko Ni, the legal advisor to Suu Kyi’s ruling National League for Democracy party, was shot and killed in broad daylight at Yangon airport. He was the highest-profile Muslim associated with the government. He had just returned from an overseas conference on the situation in Rakhine state.

There is already much speculation that it was a political assassination, intended to be a “warning” to the civilian government, although no evidence of this has yet emerged. Whatever the truth, a social post praising the actions of the killer went viral in Myanmar, demonstrating that anti-Muslim bigotry is still a force to be reckoned with.

Such considerations may explain Suu Kyi's public expression of solidarity with the military, an institution that was once her former foe, and her decision to strictly limit expressions of sympathy for the Muslim community. She opted not to attend Ko Ni’s funeral.

The British position - and that of many other nations - was to forge closer ties with the Myanamar government, while doing next to nothing for the Rohingya Muslims

While such decisions may seem squalid, they are ultimately tactical, given that, in the words of Mark Farmaner, head of the pressure group Burma Campaign UK, “Burma's so-called transition to democracy has been a transition to a new form of military control with a civilian face.”

However, there are limits to the value of diplomacy in the face of probable atrocity crimes, especially where efficacy is limited. In 2012, when the Rohingya Muslims were subject to alleged crimes against humanity perpetrated by local mobs and state security forces, no international inquiry was forthcoming. Instead, a sham domestic probe reached identical results to recent inquiries.

The British position - and that of many other nations - at that time was to forge closer ties with the Myanamar government, while doing next to nothing for the Rohingya Muslims. Consequently, the oppression of the group continued apace, with new and severe rights restrictions imposed on them.

UN: Oppression could tip into genocide

The need for justice at this juncture transcends even the importance of holding the perpetrators of recent crimes to account.

Instead, there needs to be some way to halt the forward movement of Rohingya abuse, which the UN’s special advisor on Genocide has suggested may, if enough is not done, culminate in the ultimate crime.

If the UK takes a lead in pressing for an impartial probe, then it would be an act of moral courage. Sources with links to the US embassy in Myanmar have indicated to me that the US is supportive of the idea on the ground, although the caprices of the Trump administration mean that few can predict what the final decision will be.

If the UK takes a lead in pressing for an impartial probe, then it would be an act of moral courage

If no such move is forthcoming from London or Washington, then the chances of an inquiry will be greatly diminished and the dispensability of the Rohingya Muslims reaffirmed.

The moment is ripe for Britain to live up to its self-proclaimed commitment to promoting human rights globally. Given the fear of heightening Rohingya oppression, it would seem that calling for a meaningful investigation is the least it could do.

- Emanuel Stoakes is a journalist and researcher who specialises in human rights and conflict. He has produced work for Al Jazeera, The Guardian, The Independent, The Huffington Post, Foreign Policy, The New Statesman and Vice among many others.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Image: A migrant, who was found at sea on a boat, at a temporary shelter outside Maungdaw township, northern Rakhine state on June 4, 2015 (AFP).

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.