Invasion of the stinging jellies: How the new Suez Canal is destroying the Med

It is unlikely that President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi of Egypt lies awake at night worrying about the whereabouts of the Lagocephalus sceleratus, the silverside puffer fish.

Nor, as he goes about his daily duties, is he likely to be overly concerned about the wanderings of the Rhopilema nomadica jellyfish and, so far, there have been no reports of the Pterois miles, the common lionfish or devil firefish, being among problems discussed during phone chats between the president and his new opposite number in Washington.

'The whole food web is being disrupted. Every time there is an enlargement of the canal we see a spike in the number of invasives'

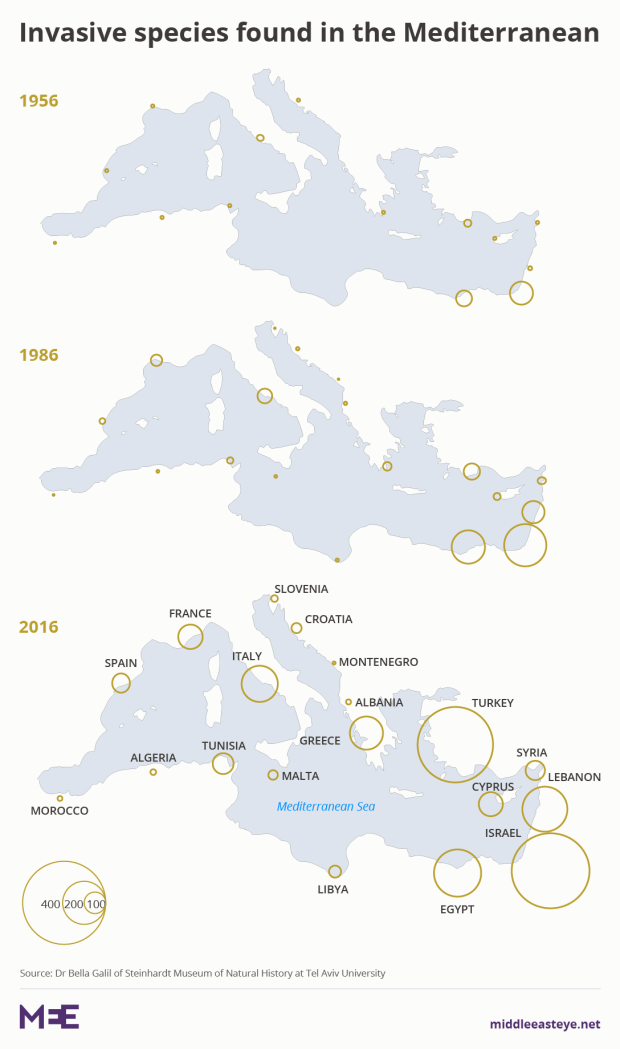

The puffer fish, the nomad jellyfish and the lionfish are among about 700 invasive species now found in the Mediterranean, particularly in its eastern region.

Scientists say a majority of those species have entered the Mediterranean through the Suez Canal and warn of a looming catastrophe as these aliens wreak ecological havoc, destroy fishing stocks and threaten the future of the region’s multi-million dollar tourism industry.

Giant swarms

“It’s unbelievable how the eastern side of the Mediterranean is changing,” says one marine biologist.

The Suez Canal is “one of the most significant pathways of marine invasions globally,” says the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

READ: Climate change: How Trump could become the world's greatest sponsor of terrorism

Ever since the Canal was opened in 1869, invasive species have been slowly migrating from the waters of the Red Sea into the Mediterranean. Some have clung to the hulls of vessels; others have made the journey in ships’ ballast.

Scientists say these migrations have accelerated over recent years; overfishing in many areas, including in the Mediterranean, means there are fewer predators to act as a control on alien populations. Old salt flats in the canal which deterred migrating species have disappeared. Changes in climate could also be encouraging a general northward movement of marine species.

Many of these invaders do enormous damage. The nomad jellyfish often occurs in giant swarms in the eastern Mediterranean, threatening tourist beaches and also blocking the outlets of coastal power and desalination plants.The puffer fish not only consumes other native species, but its internal organs also contain strong toxins which, if accidentally consumed, can cause vomiting, breathing problems and occasionally, death.

The lionfish, recently discovered colonising waters along the coast of southeastern Cyprus and in waters off the coast of Tunisia, not only has long venomous spines, but is one of the fastest breeding of all fish, capable of gobbling up the food stocks of other species.

Tourism under threat

The new canal project - a widening and deepening of the existing waterway with a 35km channel running parallel to the original – was opened with great fanfare in mid 2015.

“Egyptians have made a huge effort so as to give humanity this gift for development and construction,” Sisi said.

'We are looking at a complete ecological and economic meltdown in the Mediterranean area'

Scientists have been less enthusiastic. “Commercial considerations have trumped everything else,” Professor Jason Hall-Spencer of the School of Biological and Marine Sciences at Plymouth University in the UK told MEE.

“What a lot of people don’t realise is that these invasive species can cause considerable economic damage in the long run, threatening fishing stocks across a very wide area.”

Hall-Spencer’s views are echoed by Dr Bella Galil of the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History at Tel Aviv University who has spent years monitoring invasives in the region.

“Not only is the sea’s ecology being destroyed but the millions of dollars countries like Turkey and Tunisia have invested in tourism is under threat. The last thing visitors to beaches in July and August want to encounter is shoals of stinging jellyfish.”

'Wilful blindness'

Work on the new canal – completed in a year - was rushed through without what was considered to be a full study of its potential ecological impact.

As dredging and construction work continued, a group of concerned scientists from 39 countries wrote a letter to international organisations including the European Union in early 2015 pleading for a comprehensive, independent Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA).

READ: Why 2017 is the year Sisi will sink

“This is one opportunity to prevent, or minimise, a potential great ecological setback to the biodiversity and the ecosystem of the Mediterranean Sea that should not be missed,” said the scientists.

Scientists say no proper EIA – in line with international transboundary agreements on waterways - was carried out, though Egyptian Ministry of Environment officials say their own, as yet unpublished, EIA showed no environmental impact at all.

“The real story is the wilful blindness of various international bodies to monitor what’s going on,” says Dr Galil.

“This impacts the entire Mediterranean yet all these people are doing is talking – and taking no action. They’ve even suggested that many of these species are not invasives at all but occur naturally. Meanwhile a disaster is unfolding.”

New economic era?

The economic benefits of the new canal have been repeatedly emphasised. Egyptian officials say that by increasing the amount of shipping going through the canal, yearly revenues will increase from US$5.3bn at the end of 2015 to more than $13bn in 2023.

“Egyptians will experience a new economic era that will depend on the strength of the people and the project will be owned by Egyptians,” says Sisi.

Only months after the canal’s opening, Sisi boasted that the project’s cost had already been recouped, though he talked of a budget of $2bn while officials had earlier said the scheme’s cost was more than $8bn.

Despite the president’s claims, early indications were that the new canal was not bringing in the projected financial gains.

How to stop the invaders

Scientists have suggested ways in which the passage of invasives through the canal could be minimised. In some parts of the world, electrified fences are used to stop fish migrating. Creating a curtain of bubbles across the canal could deter many species.

Perhaps one of the most practical solutions would be to build a desalination plant along the canal. The salty brine from the plant would then act as a species barrier.

“The Suez Canal is a very important shipping corridor and a lifeline of world commerce,” says Dr Galil.

“Of course no one wants it to close, but its operation has to be effectively monitored and managed. If not we are looking at a complete ecological and economic meltdown in the Mediterranean area.”

- Kieran Cooke is a former foreign correspondent for the BBC and the Financial Times, and continues to contribute to the BBC and a wide range of international newspapers and radio networks.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A Rhopilema nomadica jellyfish swims near a diver (MEE/Shevy Rothman)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.