Fear in Trump's America: Asylum seekers speak out

AUSTIN, Texas - Claiming asylum in the United States can be a bureaucratic nightmare for some immigrants, and the Trump administration’s directives to dramatically increase deportations has made refugee communities more afraid.

President Donald Trump’s nationalistic “America First” approach has shaken the Unites States’ image as a welcoming safe haven for refugees from across the world, as evident by the northward migration of asylum seekers. By heading to Canada, they believe they have a better chance of acquiring legal residency and starting a new life.

For many, the United States has become a place that turns its back on the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” as the president portrays them as a threat to Americans’ safety and job security.

Middle East Eye spoke to two asylum seekers in Austin, Texas, about their experiences, hopes and fears in Trump’s America.

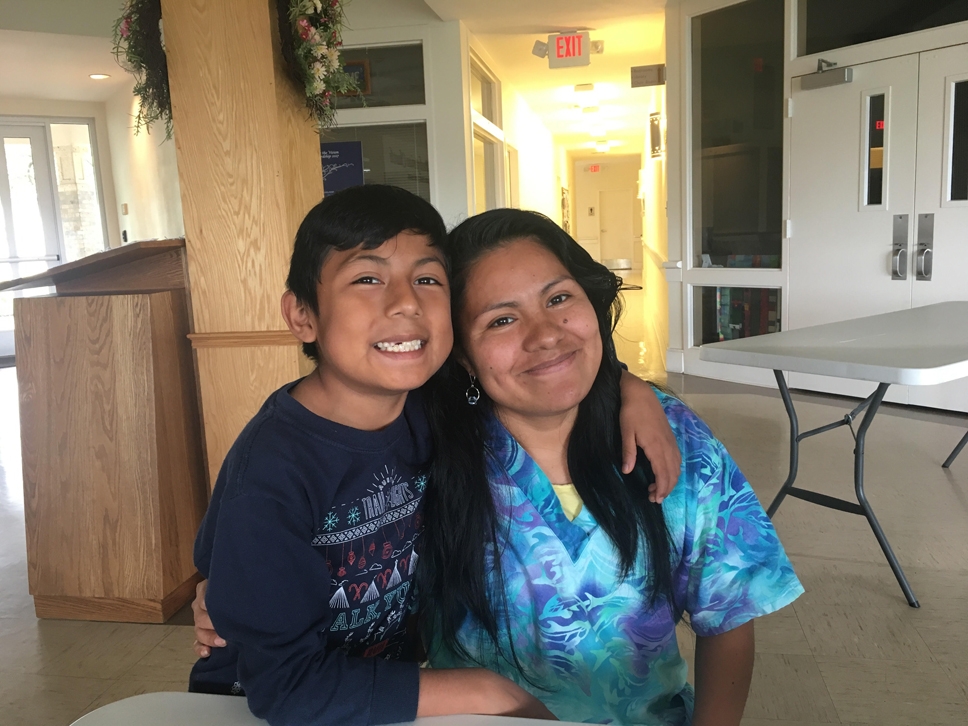

Hilda and Ivan Ramirez

Hilda Ramirez and her 10-year-old son, Ivan, arrived in the US in late July 2014 after fleeing gender violence in their native Guatemala.

“Life in Guatemala was very difficult,” Ramirez told MEE. “When I was a little girl I saw lots of abuse against women. They always valued girls less than men. My father didn’t want me to study and didn’t want me to go to school because I’m a woman. I grew up watching my father beat my mother and how my neighbours beat their wives... In my village, it was normal for men to beat women."

She added that she left because she wanted a different kind of life for her son. “I didn’t want him to grow up to be macho and to beat or hurt women,” Ramirez said.

Ramirez and her son crossed the Rio Grande river in a rubber raft. It took them more than a week to get to the US border, where she travelled by bus.

They left Guatemala with nothing more than some clothes. Ivan brought his stuffed monkey, which was ripped up by border patrol police when he and his mother were nabbed after crossing the US border.

“Crossing Mexico is really dangerous,” Ramirez said. “Cartels can kidnap you and there [are] a lot of informal cartels that are preying on people passing through Central America.”

She got in contact with a coyote, a person who helps smuggle people across the border.

“I paid a coyote to protect myself and my son as we crossed to get into the US. I had to pay $6,000 to cross the river,” she said.

The initial cost to get across the US was $3,000, but then the coyote held her and Ivan captive for four days, demanding another $3,000.

“They really charge a lot. It is such a giant business”, she told MEE.

Ramirez added that for people who don’t have the money, the coyotes pass you on to “seriously mean” cartels, who will “put incredible pressure on your family or you’re gone”.

She went on to say that if a woman doesn’t have the money, then a cartel member will likely sexually assault her.

After they crossed the Rio Grande, Ramirez described her son being in terror.

“I was terrified that they were going to take him away and I was fearful that I wouldn’t see him again. They made threats, but I kept my son close by at all times,” she said.

Immediately after crossing the border, Ramirez and her son were picked up by Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) agents.

She recalled running away through thorny bushes only to look up and find border agents right in front of her.

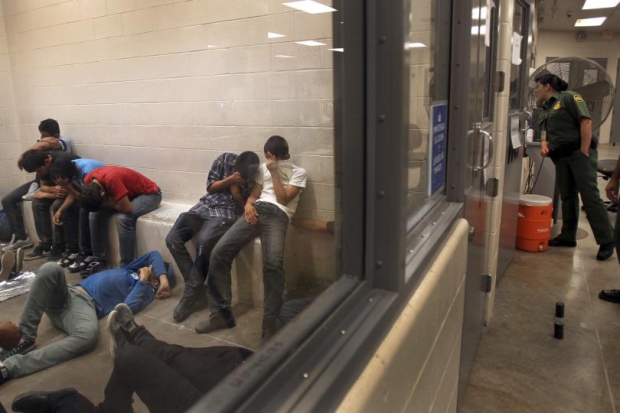

'Ice boxes'

CBP took them to a processing centre, known as a hielera, or “ice box”. She described it as a portable classroom without any furniture where the temperature is kept at 50 degrees.

“It’s very, very cold in the hielera,” she said. “You cannot wear any sweaters, we were only allowed to wear one t-shirt and a pair of light pants. The babies were always crying and they were really cold.”

They were unable to leave the “ice box,” not even to use the bathroom.

“There was only big room, and we don’t even have privacy when we go to the toilet. It was horrible,” she told MEE.

CBP kept Ramirez and Ivan there for four days. She described the guards at the facility as “warlike”.

It’s very, very cold in the hielera. Se were only allowed to wear one t-shirt and a pair of light pants. The babies were always crying and they were really cold.

- Hilda Ramirez, asylum seeker

Her son, Ivan, recalled how border police ripped up his stuffed monkey in front him.

“When they got us, they took us to the hierlera; they took my favourite monkey. I didn’t want them to take it away from me and I saw how they took out the cotton stuffing.”

Hilda interjected: “They took out the stuffing of his stuffed animal as if he was a drug trafficker. They did it front of us. Why didn’t they just go to a different room and take the stuffing out? Here’s a little boy who is already crying and they were in front of him, pulling out the stuffing.”

They were made to stay in the ice box an additional day for asking the guards why they were being mistreated, Ramirez said.

“If you don’t like how things are, what are you doing here? What did you imagine? Did you imagine that we were going to open our arms to you?” she said the guards told her.

The 'dog cage'

After her stay at the hielera, Ramirez and Ivan were placed in what they called a “dog cage,” a room whose walls are made up of wired fencing.

“When I got there, I thought it would be fun, but no. There were balls on top of the ceiling and I wished that I could get one of those balls and play. We stayed there for one day and one night. We were really bored,” Ivan said.

They were then transferred to Karnes family detention facility, a private detention complex for women and children.

She and Ivan were among the first group of people to live there when the facility opened up.

At Karnes, there were 8 bunk beds in each room. Ramirez described the bed as “small” and she said a lot of people fell off their bunks.

“It was like a jail,” Hilda said. “You had to obey all the rules. You had to get up at 5 in the morning.”

She said the guards checked the bunks several times a day and at odd hours. According to Ramirez, they checked the bunks at 1am, 8am, 3pm and at 8pm.

The conditions were so bad at Karnes - particularly the food - that Ramirez and several other women began a hunger strike at the facility. Hers lasted for 10 days.

“It was for the children. They were not giving us good food,” Ramirez said. "Sometimes the food had cockroaches in them. Other times, there would be little pieces of plastic in the food.”

She said US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents threatened to put the children in an actual prison with criminals after news of the hunger strike got out.

“I thought in the US, they protected women and children. I was really surprised,” Ramirez said.

They lived there for 11 months before a lawyer helped them get out. When she was let go, ICE put an electronic tracking bracelet on her ankle, which she called grilletes or shackles, for seven months.

“Other immigrants around me were scared of approaching me because they thought that this device would take pictures of them and incriminate them,” she said.

Through an organisation that helped refugees, Ramirez and Ivan were given sanctuary at St Andrews Presbyterian Church in north Austin in February 2016.

“I feel good here. I feel the most protected here in the church. The minister here is very nice. He is always concerned about us and has always supported us,” she said.

So far she has been living at the church, but her one-year temporary asylum status runs out in October 2017. Then, she would have to go through the whole legal process once again.

But Ramirez is hopeful despite her fear of the immigration policies of the Trump administration.

“I’m going to fight and do whatever it takes to stay here in the US,” she said.

Job

Job, he wanted to be called - an alias to reflect the suffering of the biblical prophet. He endured prison and torture in his native Ethiopia. And now he lives in fear in the United States, where President Donald Trump’s policies could force him to leave his wife and child - both US citizens - because of his immigration status.

He is an asylum seeker in Trump’s America. Job, who wished to remain anonymous for security reasons, is not a “bad dude,” but the threat of deportation looms over him.

“I had one of the strongest and most well-founded fears of persecution,” he said.

Wearing an elegant grey sweater and khaki pants at an Austin coffee shop, Job recalled, sometimes through tears, his ordeal in his home country. There, he was on the other side of the immigration system, working as a lawyer with the United Nations to help resettle Somali refugees.

His human rights advocacy got him in trouble with the government. He was arrested three times and tortured. In 2014, he fled Ethiopia after being tipped off that he may be facing serious charges because of his activism.

He had a tourism visa to the United States, where he thought he could apply for asylum status and start a new life.

I have something to contribute to this country because I know what’s happening on the other side of the world.

- Job, asylum seeker

In a 2015 report, Human Rights Watch accused the government of Ethiopia of “crackdowns on opposition political party members, journalists, and peaceful protesters, many of whom experienced harassment, arbitrary arrest, and politically motivated prosecutions”.

Here, Job was granted an interview 14 months after his initial application for asylum. In the summer of 2016 his request was denied. He was referred to an immigration court, but he is not due to appear in front of a judge until 2019.

Large backlog of immigration cases

In the meantime, he keeps his work permit - although he fits the technical definition of an “illegal alien” and may become a target of the Trump-commanded crackdown by ICE agents.

There is a backlog of 534,000 immigration cases waiting to be addressed by federal judges, with some immigrants waiting five years to appear in front of a judge, according to the Department of Homeland Security. The Trump administration is using this "unacceptable delay" to justify speedy removal for undocumented immigrants.

Job told Middle East Eye that his immigration hardships have made his life unstable. Being sent back to Ethiopia may mean that he has to spend the rest of his life in jail. It would also gravely impact his family, as he is the sole provider in the household.

Because the court date is years away, all Job can do is wait. “I am not travelling anywhere. I am not taking any plane. I am not going out of town,” Job said. “It is like you’re in a prison... I have my wife and my daughter who I have to take care of. They are citizens, but there is nothing they can do about it.”

In the meantime, he works as a taxi driver, which makes his cautious lifestyle even more difficult to maintain.

He said he carries all his immigration documents with him in case he is pulled over or questioned by law enforcement officials.

“It’s stressful, but still I have to make some money for my living and I have to feed my family,” he said. “The more you drive, the more you’re susceptible to accidents and things like that. I’m just praying that nothing happens to me on the road.”

Despite the constant fear, Job said he has found solace in the welcoming attitudes in Austin. He rejected the notion that undocumented immigrants are criminals.

“I’m not a threat to anyone,” he said, adding that he has not even committed a traffic violation during his stay in the US. “I wish those people who think that way would utilise me. I have something to contribute to this country because I know what’s happening on the other side of the world.”

The immigration system is being politicised to rob undocumented immigrants of a fair shot at making a case for staying in the US legally, he said.

Asked if he is optimistic about the future: “I do not have any viable hope in terms of the asylum application.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.