When Mosul falls: Iraq may win the war, but risks losing the peace

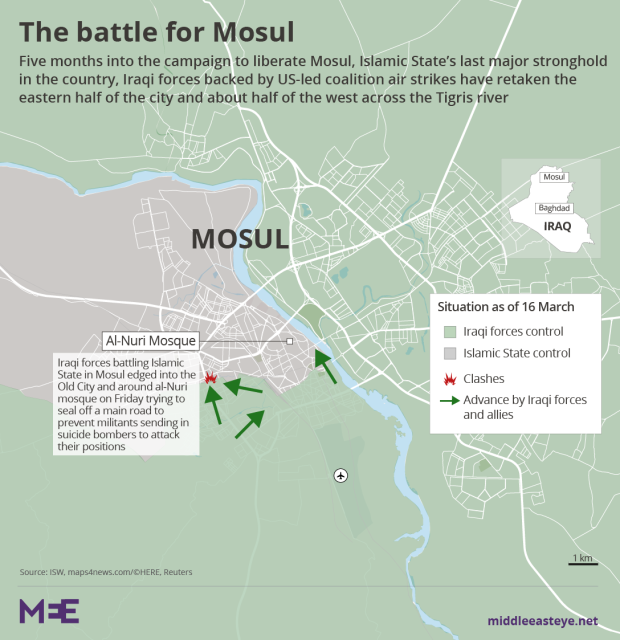

BAGHDAD - As Iraqi forces close in on the last IS strongholds in Mosul, Iraqi experts, UN and international officials fear Baghdad could find it has won the war but lost the peace.

Will military victory be followed by sectarian abuses or incompetent government administration which squander popular support and reopen the way to extremism of a new kind?

Though expressed more diplomatically, this was the question which lay behind the Iraq component of Wednesday's meeting in Washington of foreign ministers of the so-called global coalition to defeat Islamic State.

Failure would be a grim repetition of the US experience after US forces toppled Saddam Hussein 14 years ago where a quick military victory was followed by years of chaos, massacre and destruction as well as the loss of hearts and minds.

In the three months since eastern Mosul was liberated, some police are back on the streets, booby-traps are being removed, and 70,000 of the city's people have gone home.

But it took two months for schools to re-open because of delays in paying teachers and it remains to be seen what kind of local government will be installed and whether normal services of water and electricity and food supplies will be resumed.

The military campaign to retake Mosul has been more than a year in preparation so that it should have been possible to get local reconstruction geared up well in advance of the army assault.

Lise Grande, the UN humanitarian co-ordinator for Iraq, hears alarm bells ringing in areas from which IS were driven.

"Worryingly, large numbers of people are actually leaving eastern Mosul. People tell us that they are leaving because not enough food is being distributed and because they are being harassed - some even feel threatened," she told MEE.

Other officials identify some of the problems as stemming from the city's unpopular last two governors.

Atheel al-Nujaifi, the governor in charge when IS seized Mosul in June 2014, was sacked by Iraq's parliament in 2015. Nujaifi has long been close to Turkey and an Iraqi court issued an arrest warrant for him last October for allegedly agreeing to let Turkish troops into Iraq in 2015.

Some Mosul residents accuse him of alleged links with protection rackets who are preying on people in liberated areas of the city in the absence of a fully functioning police force.

Different accusations are made against the present governor, Nofal Hammadi al-Sultan. He remains in Erbil even though eastern Mosul was freed from IS grip in December.One Western diplomat told MEE that Nofal was "the most ineffective governor in all of Iraq".

"He didn't even go to Mosul to meet his staff until February. He hasn't once convened his government since liberation even in Erbil," the diplomat said.

Some wonder whether the vacuum in political authority and service delivery, after Iraqi forces fought hard to free eastern Mosul, is an attempt to punish Sunni residents for initially welcoming IS and carrying on living there, unlike people in other largely Sunni cities who mainly fled from IS.

Dhiaa al-Asadi, the leader of the MPs' group in parliament who support Muqtada al-Sadr, said this was not the prime minister's position.

There is a lack of trust between people and the government.

- Dhiaa al-Asadi, Sadrist MP

"Abadi doesn't have the view that Mosul should be punished. He says the people of Mosul are unfortunate," he said. "They were either forced by Daesh to remain in the city or they thought life would be better than it had been under Baghdad's control. Because of their hatred of the government in Baghdad they embraced Daesh."

Asadi, who calls Sadr "his eminence", said the cleric favoured having the money and responsibility for reconstruction being put under joint supervision of the Iraqi government, the UN, and the international community.

"There is a lack of trust between people and the government. There should be an impartial committee so that political parties don't use it for electoral gain," he said.

According to Western diplomats, Abadi takes a similar line, favouring a technocratic form of government for Mosul for the time being.

Everybody acknowledges that the way Mosul is handled after IS is driven out will have major repercussions across Iraq.

It was by far the biggest city to fall to IS, having a population that is more than double that of Ramadi and Fallujah put together.

Mosul's future, and the future of Iraq

A crucial issue is how to screen its citizens for what they did during IS rule.

Saad al-Muttalibi, a security expert and supporter of the former prime minister, Nouri al-Maliki, said many did not trust the people of Mosul.

"They were stupid to let Daesh in," said Muttalibi, who sits on Baghdad's city council. "But they won't repeat it. The mood in Mosul has changed because of Daesh's behaviour."

His view represents the dove-ish wing which believes Mosul has learnt its lesson from what its people went through under IS.

A harsher view is taken by Brigadier Haider al-Mattori, who commands 7,000 elite special forces soldiers of the Federal Police, led his men into eastern Mosul and is fighting on the west side of the city now.

Speaking during a leave period in Baghdad, he predicted it would take at least another two months to clear Mosul of IS due to the difficulty of fighting in the narrow streets of western Mosul's old city

The people of Mosul have no loyalty. The majority are with Daesh.

- Saad al-Muttalibi, Baghdad council member

"The people of Mosul have no loyalty to the country. The majority are with Daesh. How do I know? They're not co-operating with our forces," he said.

"Unlike the people from Ramadi and Fallujah, or Diyala and Salaheddin provinces, Mosul didn't rebel against IS. In Mosul, only 10 percent are providing us with intelligence."

He said some residents who supported the Baghdad government were leaving liberated Mosul because policemen loyal to IS were being re-appointed.

"They abuse people and if they go on doing it we will have spilt our blood in vain. They should choose police from outside Mosul," he said.

Whether Mattori's assessment is accurate or not, it highlights the difficulty of screening, and problems specific to Mosul.

"Eastern Mosul is different. Most people, in fact, more than 550,000 people, did not flee during the fighting. This means that authorities have had to use different modalities to check people."

One method is to screen people when they leave the city, even if they say their trip is brief. Another is individual screening for teachers, police and civil servants when they re-apply for their jobs.

Interior ministry officials pass people to detention centres if they are suspected of having helped IS to commit atrocities.

But officials are concerned that some of the Shia militias, the Hashd al-Shaabi, or People's Mobilisation Forces, have set up informal prisons, to which government officials have no access.

This helps alienate people from their supposed liberators.

UN officials cite the model used in Saddam's hometown of Tikrit, where Shia militias wanted to run security for a largely Sunni population. That was refused by the Stabilisation Command Cell, which is led by the local governor and includes UN representatives. The cell brought in a Sunni militia instead.

Cash is king

Overriding everything is the question of whether enough money will be available to improve public services and people's economic prospects.

At one point recently the UN had only $6m left for eastern Mosul. The US added $130m two weeks ago. There is concern that the Trump administration will cut funding as part of its general distaste for overseas aid as well as its determination to give less to the UN.

General James Mattis, the new defence secretary, visited Iraq in February. According to one Western diplomat in Baghdad, Mattis received a blunt message: "The US has spent so much in Iraq. Don't be dumb now."

The anti-IS conference in Washington on Wednesday ended with promises to support Abadi's efforts to improve public services, end corruption and ensure the equal rights of Iraqis regardless of sect or religion.

It mentioned pledges of up to $2bn for stabilisation work in liberated areas of Iraq and Syria. But those pledges must be translated into ready cash.

The UN is preparing for a funding conference on Iraq in Kuwait this summer, probably in June. It will not ask for funds for Mosul specifically, since it does not do city appeals, but Mosul will take a large part of the overall reconstruction budget.

The UN is hoping the Gulf states, which have not traditionally helped Iraq, will change their stance now. Otherwise they will be stuck on the horns of a dilemma.

When last approached, Saudi Arabia's King Salman is said to have told UN officials: Iraq is a client of Iran, go to them. When they went to Iran, they were told: we can't give you money because people will say Iraq is a client of Iran.

Mosul's future will depend to a large degree on whether that dilemma is resolved by June.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.