Israel and Palestine: One way to end the occupation

A few days ago, I was presenting the ideas of the joint Israeli-Palestinian movement Two States One Homeland (TSOH), of which I am part, before a dozen members of the Israeli Labor party's much-diminished branch in Tel Aviv. I was interrupted by one of them. "Are you Zionist?” he asked me.

I tried not to answer the question. "There are many Palestinian members in our movement," I told him, "and it may come as a surprise to you, but they are definitely not Zionist." The man was not satisfied. "Are you, you personally, Zionist?" he repeated, obviously irritated and almost menacing.

This was no simple question. If, until 1948, Zionists were those supporting the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz Israel/Palestine (and even less than a state, according to many Zionist thinkers at the time), then today the term is used to differentiate friend from foe.

A Zionist, in the current Israeli political language, is "with us", with the Jews, with Jewish supremacy over any territory Israel controls. A non-Zionist is "with them", with the Palestinians. Although TSOH clearly identifies two independent and sovereign states, Israel and Palestine, our ideas seemed anti-Zionist to this listener. Maybe because we aspire to eliminate Jewish supremacy.

A history of borders

I was born in Tel Aviv 60 years ago. My father emigrated to Eretz Israel/Palestine in 1934 (he used the term Eretz Israel, I can not take that away from him) at the age of 13. He was born in what was then Russia and is now Ukraine, and grew up in Vilnius, then part of Poland, now the capital of Lithuania. But he did not feel one bit Russian, Polish or Lithuanian. He felt Jewish. He spoke Yiddish at home and went to a Hebrew-speaking school.

I was 10-years old when the 1967 war broke. I remember the days of fear which preceded the war and the days of euphoria which followed it. Crammed in a small family car, we hurried to see the wonders of Jericho, Ramallah and of the old city of Jerusalem, before these areas would be returned to Jordan, as my parents explained to us. Stunned by the military victory, in my notebook I drew a map of Israel expanding to the Nile in the west and the Euphrates in the east and even further.

Stunned by the military victory, in my notebook I drew a map of Israel expanding to the Nile in the west and the Euphrates in the east and even further

I quickly discarded these dreams of grandeur. When Moshe Dayan, then Israel's powerful defence minister, issued in 1971 his famous phrase according to which "better Sharm el-Sheikh without peace than peace without Sharm el-Sheikh", I distributed leaflets in high school saying "better peace without Sharam el-Sheikh than Sharam el-Sheikh without peace".

The bloody 1973 war and the Camp David accord four years later, in which Sharm el-Sheikh was given back to Egypt in return for peace, were for me proof that I was right. When the Oslo agreements were signed 20 years later, I was enthusiastic. Here was a perfect Zionist solution, I told myself. We, Israelis, here in our Jewish state. They, Palestinians, in their independent state. End of occupation, end of conflict.

Peace? Further away than ever

Yet almost 24 years have passed since the Oslo agreements and peace is further away than ever. Although at least formally accepted by the leaders of Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) and the international community, the two-state solution, based on the principle of the separation of the two states, has failed to bring peace between Israelis and Palestinians. In many aspects, from the level of violence to the spreading of illegal Israeli settlements, things have only got worse. The peace process, which many described as an illusion meant to prolong Israeli occupation, is all but dead.

We, a group of Israelis and Palestinians who formed TSHO five years ago, were not surprised by the collapse of the talks led by the US Secretary of State John Kerry two years later. That's because by then we had already developed our concept, which on the one hand tries to explain why the separation model did not, and will not, work, and, on the other hand, offers a way out of this deadlock.It began with an almost-accidental meeting between me and Awni al-Mashni, a Palestinian political activist from Fatah, who spent 12 years in Israeli prisons. From this initial meeting we were very clear about what we wanted: an independent Palestinian state based on the 1967 borders, side by side with an already independent Israel, and freedom of movement for all, Palestinians and Israelis, in all parts of Palestine between the river Jordan and the Mediterranean sea, whether in Israel or in a future Palestine. We came to the conclusion that it is unpractical and undesirable to separate and divide this land - so we opted to share it.

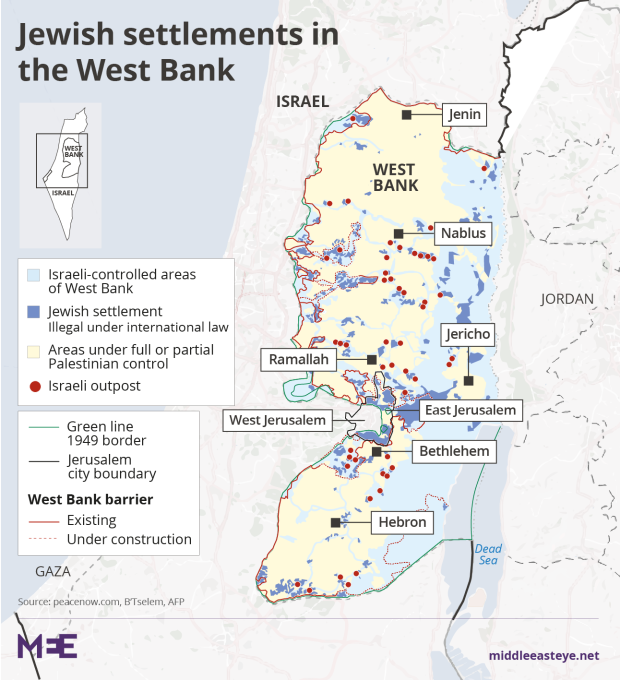

Separation is not practical because the populations between the river and the sea are mixed. Inside sovereign Israel live 1.5 million Palestinians. From the 850,000 residents in greater Jerusalem, 500,000 live in the Palestinian areas annexed after 1967, of whom 300,000 are Palestinians and 200,000 are Israelis.

Some 400,000 Israeli settlers live in the rest of the West Bank, among a population of 2.8m Palestinians. If you include Gaza, there are approximately 6m Jews and 6m Palestinians living in this land - and nobody is going anywhere.

It will require Israel not only to dismantle these settlements, but also to agree to be denied access to the places which have the highest emotional value for Jews

The supporters of the "classical" two-state solution claim that if Israel keeps the main settlement blocks, which comprise three to four per cent of the West Bank, in return for land swaps inside Israel, then it will have to evacuate 150,000 settlers at the most. This is not an impossible task, but it is certainly not an easy one. It will require Israel not only to dismantle these settlements, but also to agree to be denied access to the places which have the highest emotional value for Jews: Nablus, Hebron and Bethlehem, not to mention Jerusalem. My grandfather probably had these places in mind when he went on the Zionist marches in Vilnius.

In Jerusalem, it is even more complicated. The huge Israeli neighbourhoods built on lands occupied in 1967 are woven into the Palestinian neighbourhoods and villages around them. And even the staunchest supporters of the separation model know it's impossible to divide up the old city or the Haram el Sharif/Temple Mount. Their solution is to create an international regime in this area. But if they agree to share these very sensitive places, the cause of so many violent clashes between Jews and Palestinians during the last 100 years, then why can't we share the whole of the land?

What about the Palestinian refugees?

Then there is another huge issue: the Palestinian refugees. According to the most generous separation models, Israel will agree to absorb 100,000 refugees. Up to 6m Palestinians in the diaspora will have to surrender their right to return to the places from which they were exiled. It took me years, as an Israeli, to understand that such a partial return will be a "hudna", a truce, between two wars, as my friend al-Mashni use to say.

The most appropriate tool to reach this goal – according to TSOH - is through an Israeli-Palestinian confederation, which will resemble to a great extent (but not copy) the model of the European Union: two independent states with designated borders, which will transfer some of their powers to shared institutions in various fields, from human rights to security, social rights, environment etc.

The ideas of TSOH are based on two principles: the right of Israelis and Palestinians to self-determination in their independent states; and freedom of movement and access for everyone, Israelis and Palestinians, all over this shared homeland. We think that this is the key to achieving relative justice on the one hand, and long-term stability on the other.

There will be freedom of movement and gradual freedom of residence across these borders. Palestinians will be able to live in Israel as Palestinian citizens with Israeli residency living under Israeli sovereignty, but enjoying the protection of these confederal institutions. This will apply also for Palestinian refugees. They will have freedom of access, and gradual freedom of residence, in the places they are currently exiled from.

Palestine and Israel will share sovereignty over Jerusalem, which will be governed under a special regime and will remain an open city, run equally by its own people, Israelis and Palestinian alike.

This may seem naive and wishful, especially under the current state of ongoing occupation, killings, ever growing settlements and total lack of trust between these two peoples. We are painfully aware of this reality, yet we firmly believe our ideas are the most realistic way to achieve peace because they acknowledge the realties created over these last 100 years and at the same time give a fair – although not full – answer to the aspirations of both Israelis and Palestinians.

Palestine and Israel will share sovereignty over Jerusalem, which will be governed under a special regime and will remain an open city, run equally by its own people

During the late 1980s, Shimon Peres promoted a Jordanian-Palestinian confederation. This idea stood as the basis of the London accord between him and King Hussein of Jordan. Yitzhak Shamir, then prime minister, rejected the agreement but it is doubtful if there was any real chance of implementing it, as Peres' main motive was to prevent the establishment of an independent Palestinian state.

Confederation is not really a new idea in the framework of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In fact, the 1947 UN Partition Plan envisaged a confederation between the Jewish state and the Arab state with economic union and open borders. The Jewish Agency accepted the plan, the Palestinians rejected it then, but probably would have accepted it now.

Yossi Beilin, who was Peres' aide at the time, told me that Faissal Husseini, one of the chief negotiators for the PLO, asked him why Peres was pushing the Palestinians into a confederation with Jordan. “We prefer a confederation with Israel," Husseini told him, according to Beilin. Now Beilin thinks that Husseini was right and that the road to achieving a two-state solution passes through confederation.

The layer of ice on which Israelis live

Today, as it celebrates the 69th anniversary of its independence, Israel seems more stable than ever. The level of violence in the conflict with the Palestinians is low, the economy is doing well and with the civil wars in Syria and elsewhere, there is no real external threat.

Occupation is still with us after 50 years. We have the duty to end it, but we want to end it with a solution which will give justice for all

The answer which Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is that Israel should stick even more firmly to the status quo of occupation. In order to achieve it he tries to delegitimise all those who seek to change this course. But despite all these seemingly reassuring features, the layer of ice on which Israelis live is thin. Many, if not most, Israelis feel insecure and fear for their future.

Although the word "occupation" is rarely used in Israeli media, Israelis are aware, consciously or unconsciously, that the international legitimisation of Israeli occupation, and even of Israel's own existence, is eroding slowly and steadily.

It works very well for him. Not only do his coalition members violently attack anyone remotely suspected of sympathy with the Palestinian but even the centrist Yesh Atid party, headed by Yair Lapid and the Labor party, join the chorus. This is why human rights organisation such as B'tselem and Breaking the Silence are delegitimised daily. This is why I was given this Zionist litmus test in the Labor party's branch in Tel Aviv.

My parents were sure that Israel would withdraw from the territories it occupied in June 1967 in a matter of weeks. They were wrong. Occupation is still with us after 50 years. We have the duty to end it, but we want to end it with a solution which will give justice for all.

- Meron Rapoport is an Israeli journalist and writer, winner of the Napoli International Prize for Journalism for an inquiry about the stealing of olive trees from their Palestinian owners. He is ex-head of the news department at Haaretz, and now an independent journalist.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Image: Palestinian scouts outside the contested Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem in April 2017 mark the Prophet Mohammed's ascent to heaven (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.