I ran an illegal beauty salon: The secret lives of women under Islamic State

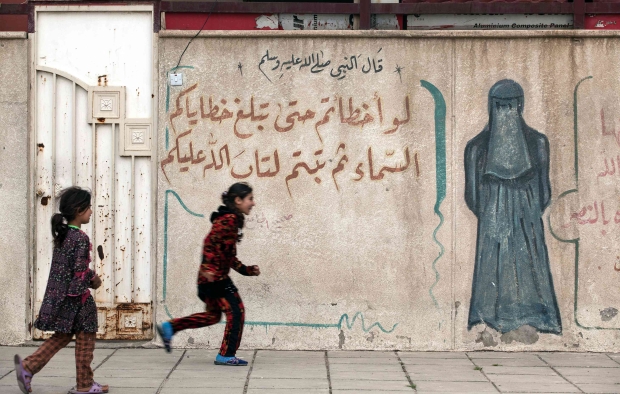

MOSUL, Iraq - The graffiti scrawled on a low wall close to a lively shopping street is one of the last vestiges of Islamic State propaganda in eastern Mosul. "The real beauty must be hidden," it reads. Next to it is a drawing of a fully covered woman.

The group may have been driven from the neighbourhood but it still terrifies Anwar.

We meet in the beauty salon that the 29-year old mother has recently opened. The walls are pink, the shelves full of makeup, curlers and wigs. In the background a small television broadcasts the call to prayer from Mecca. Anwar's face is hidden by an orange scarf. On the back of her jacket the word "Chanel" is picked out in glitter.

When IS arrived in Mosul, Anwar refused to stop hairdressing, despite it being strictly prohibited. Instead, she rebelled in her own quiet way, running a secret beauty salon at home for the women in the neighbourhood, buying cosmetics – which were also banned – on the black market.

"When IS controlled Mosul, I worked illegally at my home," she said. "At the beginning, IS didn't know I was running an illegal beauty salon in my house."

News of the salon spread among women in the neighbourhood who would meet in each other's homes (they could only meet in public iif accompanied by a mahram - that is, a man of their family, be it their husband, cousin or father). But soon, word got out and an IS policewoman came to Anwar's home.

"They screamed at me and threatened to strike me if I did not stop it," Anwar said. "I have four kids, my husband is sick. I have no other choice if I want to feed them."

'They beat my husband. I had to stop and stay at home doing nothing'

- Anwar, beauty salon owner

But Anwar refused to stop and kept the salon open. "They said: ‘If you want to complete your job inside home, no problem, but you must pay us money, like half. Some days I made 65,000 Iraqi dinars [US$55] and IS came to take half of it."

When IS asked for more, Anwar couldn't pay. Eventually the hisba – an Arabic word for accountability, which IS uses as the name for its police force - arrested Anwar's already ill husband for allowing his wife to break IS law. "They beat my husband," she said. "I had to stop and stay at home doing nothing."

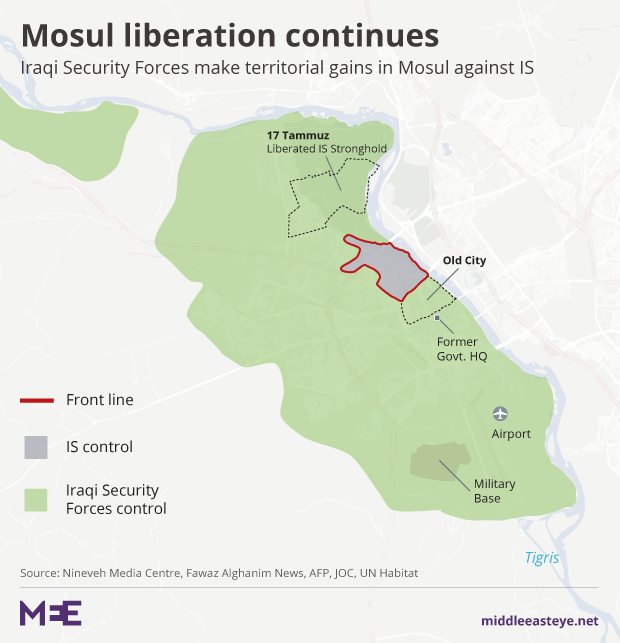

Suddenly Anwar was interrupted as the muffled noise of an explosion rings out from the western side of the city, where the Iraqi army is trying to dislodge IS, then she continued to speak.

Customers, she said, have slowly started to return to her salon. "But they are still afraid that IS may come back. I am still afraid," she said, quivering. Fear of recapture – and what may happen - weighs heavily on her mind.

A woman's place

For two-and-a-half years, Mosul, a conservative urban area of around 1.7 million people in 2015, became a full-scale experiment in IS ideology.

At first, some residents welcomed the group with curiosity, confided one teenager. "We thought that they were going to teach us some good Islam," she said. Maryam Nazar, 25, a doctor added: "In the beginning, the soldiers were not too strict, almost pleasant."

Prohibition after prohibition followed. The female wardrobe was reduced to five compulsory pieces: socks, black gloves, a jilbab or abaya, a niqab and an extra veil to shield the eyes.

Step by step, women's rights regressed. In February 2015, an IS manifesto published online stipulated that "the fundamental function of the woman is to be at home with her husband and her children".

In markets, women could have no contact with male stallholders. Instead they would indicate what they wanted to buy, look down so as not to meet the shopkeeper's eyes and put the money on the table. The seller would then take the money without touching the women's hand. The punishment for not following the rules could be severe.

'The man asked a woman to whip me because of the gloves and my attitude.'

- Am Nour, mother

Am Nour, a 40-year-old mother who lives in a working-class neighbourhood of Mosul, still has nightmares about the hours she spent in a prison run by the hisba.

Nour was in an understandable panic on the day in question: her son was in a car accident, she was rushing with her husband to the hospital, she forgot to take the mandatory gloves that IS expects all women to wear.

Then, at a street crossing, she was spotted by a member of the hisba. "Why does she not have gloves?" the IS member asked her husband. "It is against Islam."

Nour told him that wearing gloves was not a requirement of Islam. "He then railed: 'What, you want to teach me Islam?'," she recalled. "I roared that my son was sick, that had I to go to find him."

The hisba member grabbed Nour’s arm, pushed her in a police van and tied a scarf tightly around her eyes. "I saw nothing during the journey, which lasted 10 minutes," she said. "Then I arrived at a house."The man asked a woman to whip me because of the gloves and my attitude. Around me, I heard other women shouting," she said. "I still feel pain in my back because of this."

Nour was eventually released, at the same location where she had been picked up.

Bleak futures

Authors Nadje Al-Ali and Nicola Pratt believe women's rights in Iraq have regressed since the American invasion of 2003.

In their 2008 book What Kind of Liberation: Women and the Occupation of Iraq, they wrote that, for the conservative fringes of society, "women are symbolic markers of the break from the nominally secular Saddam Hussein regime and a means of differentiating Iraqi society from the" foreign culture "of the United States and its allies.

It's a view echoed by Fatima Hashim Nury. A humanitarian worker for Al Mesalla, an NGO which focuses on women's rights, she works in refugee camps between Mosul and Iraqi Kurdistan.

"Mosul was an already conservative society," she said of life before IS, "and it is one of the reasons why Islamic State was able to establish itself."

She cited education as one example. "We can say that 20 percent of children were going to school when IS ran the city. For small girls, it was around five percent. IS mostly prevented girls from attending school, except maybe for elementary classes."

'Women don't think about freedom or future, just what they can do for their children. We had a first generation under bin Laden, then another with al-Zarqawi, then Islamic State. What’s next?'

- Fatima Hashim Nury, Al Mesalla

The outlook for the city, she said, is now bleak. "In Mosul, there is nothing any more, no schools, no university. There is no life here. People don't have water, don't have electricity, don't have food. Whether it is on the west or east side of Mosul. There is no life here."

Maisun Ahmed, 57, is the director of a college for girls in their late teens in Gogjali, an eastern suburb of Mosul. Biology dissection charts, prohibited by IS, once more hang from classroom walls. Under IS, male teachers were not allowed to teach female pupils.

Ahmed, tall, wrapped in a black coat and with her hair covered in a beige veil, is herself a strict presence. But she is now scared for her own safety: in areas liberated from IS, there are now witch-hunts that target any person with a link to the group, whether their involvement was under coercion or voluntary.

Ahmed kept her job while IS was in power. "I had no choice," she said, miming a beheading action with her hand.

"We had 300 pupils before, but under IS we received no more than seven and they were all IS daughters." Those pupils are no longer present. "They must have gone to the western side of Mosul," she said.

At break, a visit by foreign journalists evokes curiosity among the pupils. They want to speak, to be heard. "It's like life had stopped for almost three years," said one student, now wearing pink sneakers. Another added: "We believed that we could never return to school."

Almost all want to become doctors. "Today, we can dream again, we feel free," said a third.

But nothing is certain.

After almost three years of living under IS ideology, residents have been left mentally scarred. Despite heavy losses, IS has yet to be wiped out. Hundreds of thousands of people have been displaced across the country, shaking a social structure that was still recovering from the 2003 invasion.

"Many mothers have told us that they fear their children are still brainwashed by Islamic State ideology," said Hashim Nury.

"Women don't think about freedom or the future, just what they can do for their children. We had a first generation under bin Laden, then another with al-Zarqawi, then Islamic State. What's next?"

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.