No, the Iranian president is not about to be ousted

Hassan Rouhani’s landslide victory in May’s presidential elections has raised expectations among his supporters and the wider electorate that he’d enjoy a much freer rein during his second term.

The perception that Khamenei is somehow aligned with the conservatives and principalists against Rouhani is wrong at many levels

But this is proving to be a forlorn hope as the establishment and allied principalists mobilise to contain Rouhani’s ambitions.

The more extreme side of this campaign was brought into sharp relief during the last month's Quds day rally - Iran's annual display of support for the Palestinian territories - when a group of rogue protestors chanted slogans against Rouhani, calling the president an “American cleric” and comparing him to the republic’s first ousted president Abol-Hassan Banisadr.

This principalist campaign coincides with an escalating spat between Rouhani and the high command of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) over a wide range of issues, notably the economy and foreign policy.

Second Banisadr?

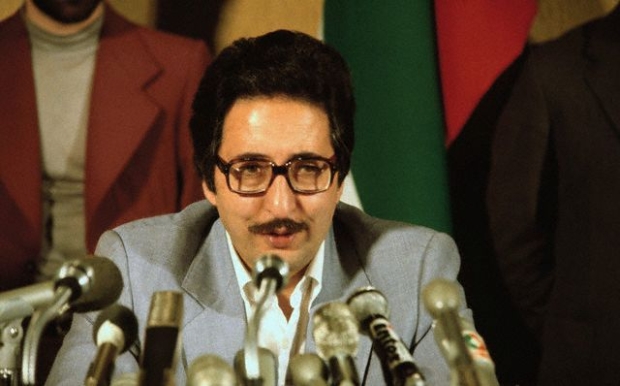

In recent weeks, Rouhani’s opponents have increasingly compared him to the Islamic Republic’s hapless first president, Abol-Hassan Banisadr. This comparison was prompted by last month’s warning by the leader Ayatollah Khamenei that the events of 1980-1981, when then-president Banisadr “polarised” the national scene, should not be repeated.

Rouhani’s opponents have increasingly compared him to the Islamic Republic’s hapless first president, Abol-Hassan Banisadr

Banisadr was the first and last Iranian president not to serve two full terms. In fact, his first term was abruptly cut short when he was impeached by the Majlis (Parliament) in June 1981 for alleged subversive activities. He subsequently fled into exile and currently resides in Paris.

A gadfly intellectual, Banisadr was fundamentally at odds with the core power centre of the Iranian revolution which revolved around the late Ayatollah Khomeini and his closest advisers. He fit neither the image, nor the ideology that was being consolidated in the immediate post-revolutionary period. Moreover, his eccentric intellectual style, and lack of political skills, meant that he could not form alliances with key powerful individuals and groups.

By contrast, Hassan Rouhani has been a stalwart of the Islamic Republic for nearly four decades. He has had leading roles in the Iranian national security establishment, including long stints in the Supreme Defence Council and the Supreme National Security Council. Crucially, despite significant differences with leading figures in the establishment, including the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, Rouhani is not distrusted by them.

Additionally, even though he lacked political experience prior to 2013, Rouhani has proven to be a capable politician with the ability to form and sustain broad coalitions. His alliance with the reformists secured a comfortable victory in the March-April 2016 parliamentary elections.

It was this centrist-reformist alliance that formed the basis of Rouhani’s landslide victory in May’s presidential poll. Rouhani’s own centrist powerbase gives him sufficient institutional reach within Iran’s most sensitive institutions, including the intelligence services, which are currently led by Rouhani loyalists.

In summary, Rouhani is as far removed from Banisadr as is possible. Talk of formal impeachment or less constitutional means of overthrow are usually made by Rouhani loyalists who are anxious to radicalise the environment with a view to pushing back against the principalists and hardliners. The reality on the ground, however, is that even the most hardcore principalists are opposed to sloganeering against Rouhani, let alone setting the stage for him to be ousted.

A balancing act

The campaign against Rouhani intensified in early June when Ayatollah Khamenei encouraged his supporters to “fire at will” in response to perceived political and cultural atrophy in the Islamic republic.

Although Khamenei issued this advice to activists specialising in “soft” warfare (for example cultural and political agents), it nonetheless caused enough controversy and misunderstanding for Khamenei to qualify his advice by emphasising that “firing at will” shouldn’t amount to “anarchy”.

The perception that Khamenei is somehow aligned with the conservatives and principalists against Rouhani is wrong at many levels. Foremost, Khamenei’s speech last month was addressing the general direction of the country during a period of acute regional tension and stress. At any rate, from an institutional point of view, Khamenei’s overriding priority is to create balance between Rouhani and his principalist opponents.

Second, there is no coherent or wide-ranging principalist position on Rouhani. On the contrary, at the institutional level at least, the principalists are deeply split. Inside the Majlis (parliament), principalists are divided into anti and pro-Rouhani camps. The main “Principalist Followers of Velayat” faction (which is anti-Rouhani) is now balanced by the pro-Rouhani “Independent Followers of Velayat”.

Realistically, the most anti-Rouhani factions in the Majlis can hope for is to lobby alongside IRGC commanders to moderate Rouhani’s policies in the course of the next four years. In the economic sphere, the principalists and their IRGC allies are not so much opposed to Rouhani’s economic plans in principle, as they want the IRGC to remain involved in major infrastructure projects. The $5bn deal with France’s Total and China’s National Petroleum Corporation is case in point.

On foreign policy, the desired outcome from the IRGC’s point of view is for Rouhani to abandon his soft rhetoric on regional and international foes. The pressure appears to be working as Rouhani slightly dissented from his trademark moderate tone at an environmental conference by telling Iran’s foes that the era of “building walls” had come to an end. It remains to be seen whether Rouhani can stay on message.

- Mahan Abedin is an analyst of Iranian politics. He is the director of the research group Dysart Consulting.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: During this year's election campaign, Rouhani waves at a rally in the northwestern city of Ardabil on 17 May 2017 (AFP)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.