Playing Palestinian poet Taha: ‘I carry that Nakba on me 24 hours a day’

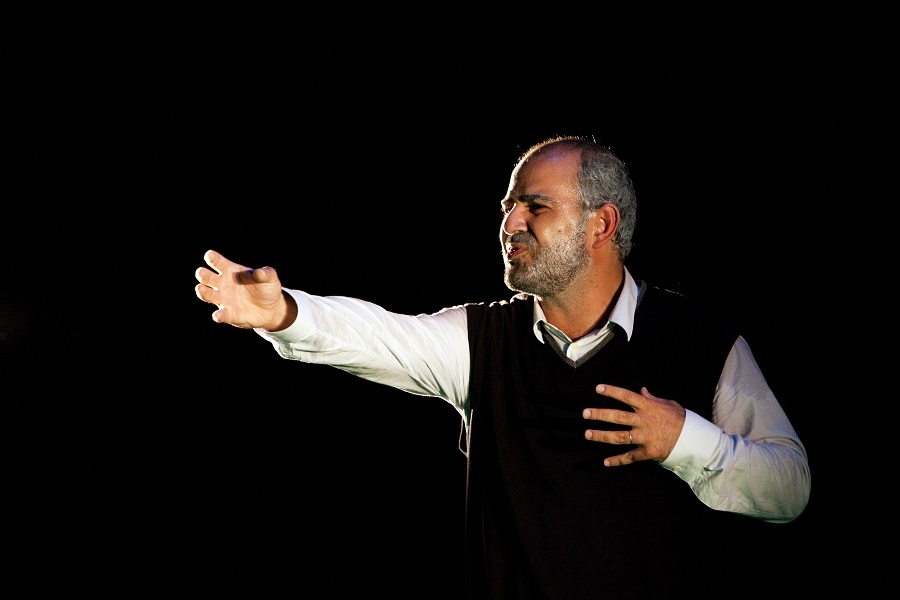

LONDON - Amer Hlehel paces the dark stage in circles, occasionally halting and swaying under the spotlight, as if struggling to remember something.

Hlehel is playing the great Palestinian poet Taha Muhammad Ali (1931-2011) in a performance at London's Young Vic theatre as part of the Shubak biennial festival of Arab culture.

The actor and writer - himself, like Taha, a Palestinian from Israel - speaks most of his lines in English. It’s a tumbling of words, engaging and warm, as the audience listens rapt to a master storyteller recounting his life from his near miraculous birth to his experience of the Nakba (Catastrophe) of 1948 and his later emergence as a renowned poet.

Taha begins and ends with the line: “In my life nothing came easy. I came into the world despite its will, it never wanted me.” Hlehel explains to Middle East Eye that the line is his, not the poet’s. “I think the original Taha wouldn’t say this line, because he was a very optimistic person, but I think for the play it was right to say it, because nothing came easy for Taha.”

Only his poems are spoken in Arabic, translated on the screen behind the actor. The work is based on Hlehel's Arabic original that was performed in Palestine in 2014, and translated by long-time artistic collaborator Amir Nizar Zuabi, who is directing Hlehel in London.

The harshness of Taha's early life is captured movingly in the play. Despite being the first of five children to survive infancy - a passage that is both shocking and told with surprising levity by Hlehel - Taha grew up to be a star student, learning English from the BBC by listening to the village’s only radio.

Village razed

He was also a budding entrepreneur, determined to overcome the poverty of life in his village. He sold eggs and other merchandise off the back of a neighbour's truck in nearby Haifa and looked after his family when his father no longer could.

But his dreams of building an apartment block for his beloved Amira and family members came to a shuddering end in 1948 when one night two planes flew over and dropped bombs on the village. He and his family fled to Lebanon's Ain al-Hilwell refugee camp, where more tragedy hit the family. They eventually returned to the new state but the village in the Galilee, called Saffuriya, had been razed during the Nakba.

Hlehel’s reasons for writing the play are personal. His own family shared almost identical experiences to Taha’s during 1948 and its aftermath. “Taha’s story is [a] very similar story to my grandfather’s story. My grandfather was displaced and his village was destroyed. They went to Lebanon for one year, and he sneaked back from the same refugee camp, Ayn al-Hilweh. He lost everything - his land, village, environment, family. But he built again his family in a new place, in a new village. He was not allowed to enter his old village for rest of his life.

“I am a result of this story, I carry that Nakba on me all the time, 24 hours a day, wherever I am. For me it is something very personal, so doing this story and through a man who could express and describe this catastrophe with this deepness and so tender, it’s a meeting between the tender, personal story and the collective Palestinian story.”

Taha's free verse

Taha is important both as a great storyteller of the Palestinians but equally as a new kind of Arab poet who broke ground with his free, intimate style, explains Hlehel. “There’s no meter, [it is] very free, new and fresh … In the Palestinian aspect, it is very human and personal, this was also something new."

Taha emerged in the 1970s as a new voice in Palestinian poetry alongside others such as Mahmoud Darwish, the best-known poet of the post-1948 generation. "Mahmoud Darwish was speaking about the political, collective, the voice of the people, it was poetry written for being read on stage for a crowd," said Hlehel.

"Taha is the first to write about the same issues, the same story but from a very personal point of view, about his loss, love, small details in his small village, without trying to be a defender or a lawyer for others. This became the poetry that people connect to because of his very personal [style].”

'It is very dangerous what I’m going to say: Taha’s poetry about the Palestinian catastrophe lasts much more than Darwish’s poetry'

- Amr Hlehel

He goes further, putting his neck out. “It is very dangerous what I’m going to say: Taha’s poetry about the Palestinian catastrophe lasts much more than Darwish’s poetry. Even Darwish’s last 15 years of his life, he didn’t write political poetry - he said he just wanted to get rid from it. It was very naive and political, not so deep and personal. I think this is what makes Taha very special in the Palestinian poetry scene.”

Before its London run, they took Taha to the centre of power in Trump’s America, to the Kennedy Centre for the Performing Arts next to the Watergate Centre in Washington DC. For Hlehel, to be able to present a personal Palestinian story of the Nakba in the US at this time is a positive sign, despite all the bad news coming out of Palestine and Israel.

“There are people there who are brave and not afraid to bring a pure Palestinian story and told from a Palestinian point of view and not bringing, you now, the other side into it… I think something is changing about how the world is looking at the Palestinian case and the Palestinian story.”

Brave partner

Looking at the political landscape more broadly, Zuabi is less optimistic, saying with grand understatement: “The situation in world politics doesn’t look very peachy right now. It might backlash and that’s our hope. This rubber band has been stretched and stretched and stretched and it could snap back.”

In the UK, Zuabi sees the Young Vic under director David Lan as a brave partner which is committed to bringing the Palestinian voice to UK theatre. “Politically most directors are not as brave as David Lan,” says Zuabi, in providing a supportive environment for work about the Nakba and its ongoing consequences.

“When we were doing I am Yusef, there are things he is willing to do, because they are good stories... Unfortunately, most of the theatres would not have been committed in this way.”

Lan has worked with Zuabi for a decade and helped bring numerous plays to London, including I am Yusef and This is My Brother. He himself has visited Israel many times. "In all of this," he tells me after the show, "it always comes back to 1948,” adding that the traumas of the 1940s are something that neither Jews nor Palestinians can escape. He modestly agrees that the work the Young Vic is doing with Palestinian artists is important, even unique.

Band of brothers

Zuabi and Hlehel have worked together since they co-founded the Shiber Hur theatre in 2009 in Haifa. They met after Hlehel saw one of Zuabi’s plays and was blown away, and have worked together ever since. “From very first project,” Zuabi explains, “I knew I found a wonderful actor but also somebody much more than that, a collaborator, a partner and someone who can challenge you and be challenged, an instant partner. Our scene is so tiny and scattered in Palestine. There are links because we need each other.”

This is a special aspect of the Palestinian theatre scene, Zuabi adds. “We have amazing artists with something to say, and a lot of intimacy because we are a band of brothers. When we do theatre, it feels we are going into a lost battle. Even after 15 years of us doing productions, I am always bewildered we get these productions done when everything is stacked against it.”

Hlehel also works with Palestine’s award-winning film director Hany Abu Assad, starring in his Golden Globe award-winner Paradise Now (2005) and more recently in The Idol (2015), a biopic of Gaza’s singing sensation Mohammed Assaf.

'When we do theatre, it feels we are going into a lost battle'

- Amir Nazir Zuabi, director

The beginning of their collaboration was inauspicious, coming amid a bloody Israeli crackdown in Nablus. “We met in 2004. It was a very terrible time in the middle of the Second Intifada, and we shot this film in Nablus in 2004 and we were in danger - the whole city was in danger, not just us, and bombing every day from [Israel’s] air forces, and dead people, dead bodies all the time in the streets. Me and Hani we became really close, we became friends.”

He compares the way Zuabi has brought the Palestinian voice to the world through theatre with what Assad has done in cinema, the first from Palestine to win a Golden Globe for Best Foreign Language Film in 2006. “For the first time the word Palestine was said on stage in the Golden Globes. For us it was a huge step for the recognition of Palestinians in the world on the arts scene.”

Zuabi sees Taha as an example in how he lived his life, as a self-educated Palestinian poet selling Christian souvenirs to pilgrims from his shop on Casanova Street in Nazareth. “We need to get on and do what we can in our lives, and this is what he has done.”

As Taha said in an interview shortly before his death in 2011: “In my poetry there is no Palestine, no Israel, but in my poetry there is suffering, sadness, longing, feeling, and this together makes the result - Palestine and Israel.”

-Taha continues at the Young Vic until 15 July and then transfers to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, 2-13 August.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.